Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

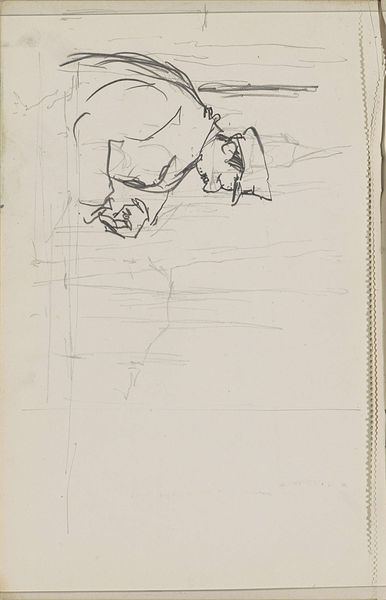

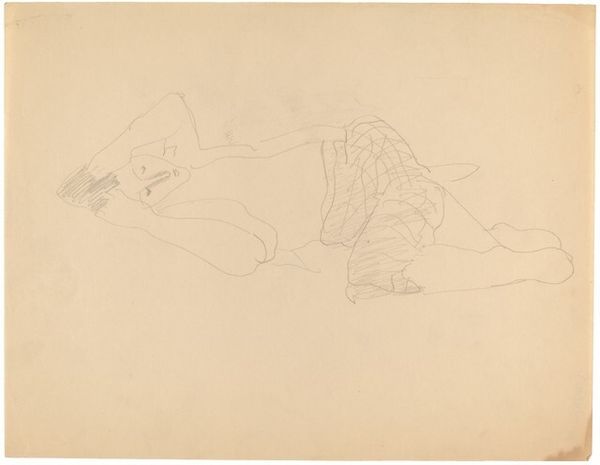

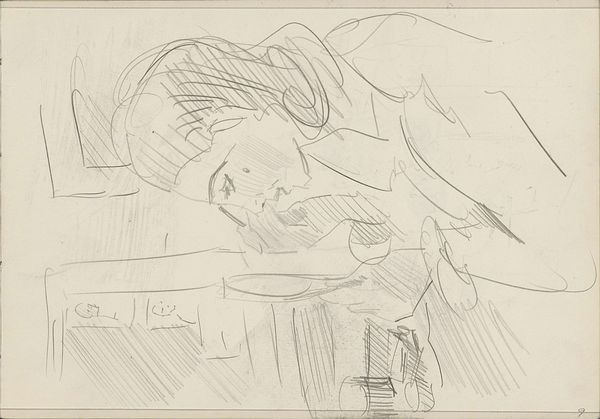

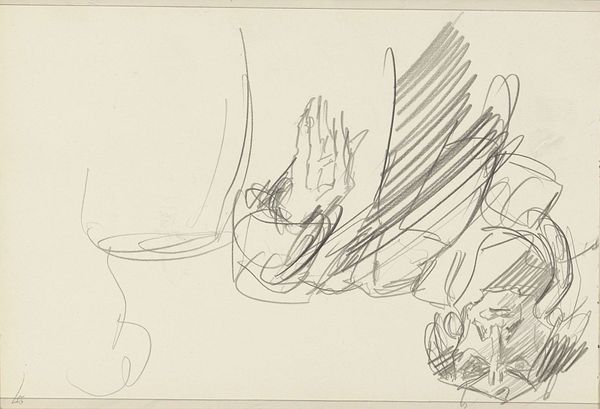

Curator: At the Rijksmuseum we find this pencil drawing by Isaac Israels. The piece, dating from 1875 to 1934, is called "Zittend vrouwelijk naakt en een staande vrouw" – or "Seated Female Nude and a Standing Woman." Editor: There’s something incredibly haunting about the loose sketchwork, as if we are viewing a fragmented dream or perhaps an unedited view into Israels’s subconscious. Curator: Israels was deeply invested in depicting modern life in the Netherlands. He gravitated towards scenes of work and leisure. During the time he created this work, ideas about gender and representation were changing rapidly. His connection to Impressionism can really be observed here. Editor: I’m intrigued by the juxtaposition of the clothed woman, who appears to be a silhouette, against the detailed rendering of the nude figure. It's as if he's posing questions about the gaze, about visibility and invisibility. Is he challenging the prevailing societal views of the time regarding female representation? Curator: Absolutely, and given the rise of photography, this pencil work is inherently questioning how and why we produce images. Was there even a ‘need’ for artwork such as this, given the availability of representing real people at that time? It should be said that Israels wasn’t as groundbreaking as his contemporary Breitner. He didn't make any clear societal or political statements within his art. Editor: True, but there's still a rawness, an immediacy in the lines that invites the viewer to question these issues themselves. Curator: It’s worth considering Israels’s own biography when engaging with this work. As the son of Jozef Israels, a leading figure of the Hague School, he navigated an art world already shaped by tradition and expectation. Editor: This piece makes me think about how identity itself becomes a performance. It evokes a whole constellation of discussions concerning how women’s bodies are represented. The relationship between artist and model, viewer and subject – what does it all mean within a patriarchal context? Curator: An engaging set of questions which demonstrate, perhaps, that some conversations are eternal. Editor: It encourages us to consider how social constructs still dictate who gets seen and who remains in the shadows, even within a simple drawing like this one.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.