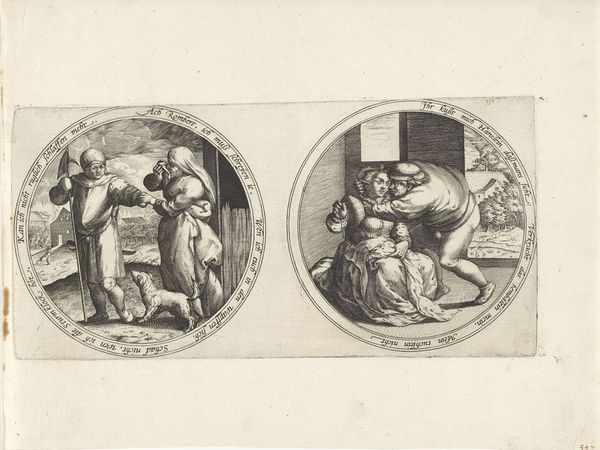

Echtpaar met een spiegel en een visser die een vrouw een vis overhandigt 1555 - 1631

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

narrative-art

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 150 mm, width 308 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This intriguing engraving at the Rijksmuseum, titled "Echtpaar met een spiegel en een visser die een vrouw een vis overhandigt"—loosely translated as "Couple with a Mirror and a Fisherman Offering a Woman a Fish"—invites layered readings of its historical moment. Attributed to an anonymous artist and dated somewhere between 1555 and 1631, it presents two circular scenes. What strikes you first about its composition? Editor: Immediately, I notice the starkness of the engraved line, the precision of the tool biting into the plate. The artist's labour, painstakingly creating these two worlds, the almost allegorical feeling of these contrasting scenes. It looks extremely material, I wonder if it had to do with wedding practices, perhaps the beginning of bourgeois practices of gift exchanges. Curator: That's a compelling point regarding the material gift as an emblem. It echoes with narratives around courtship rituals and gendered economic exchanges. The image on the right presents this quite literally with the exchange of fish from a male figure to the young lady, who is possibly being tempted into this deal with fish that could symbolise the wealth being offered and her power. While on the left there's an aged couple in bed with what seems like a child? Are they reflections on ageing? Or family ties? The material and meaning have a direct social commentary. Editor: The social element is undeniable, particularly within the medium itself. This work wouldn’t exist without the specific tools and processes required. You're totally right, it raises the idea of generational exchanges, the continuity of labour, from the fisher to family ties, through the means of providing with gifts! Curator: The medium’s dissemination, through printmaking, means these themes reach broader audiences, shaping discourses about social and economic relationships—specifically about social hierarchy and social capital through gender in European families during the era it came from. What the message delivered could be very impactful to cultural norms and customs that might not be available to common viewers like us. Editor: Exactly. The act of repetitive printmaking underscores the act of standardized labor that enables visual propaganda of wealth to occur, as in fishing or relationships, where gifts in the image are then proliferated and consumed en masse in European popular media. The meaning could potentially be skewed by social interpretation with class in mind, which would ultimately turn into further political arguments of family planning. Curator: Thinking through these various intersections allows us to appreciate its role, a humble-seeming print, which had considerable resonance in broader social narratives. Editor: And looking at the materiality opens our understanding of the period, helping reveal labor practices and political tensions within European history and beyond, from gender all the way to ageism.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.