drawing, print, paper, ink, pen, engraving

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

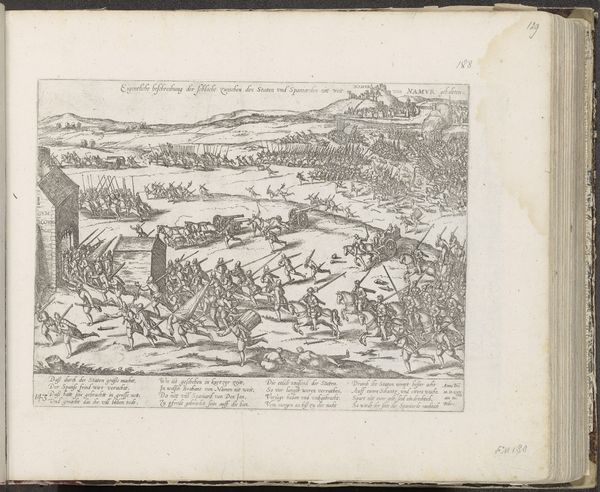

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

sketch book

#

figuration

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen and pencil

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pen

#

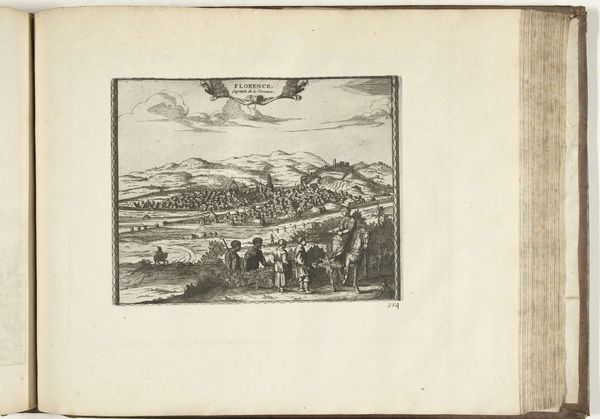

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

#

realism

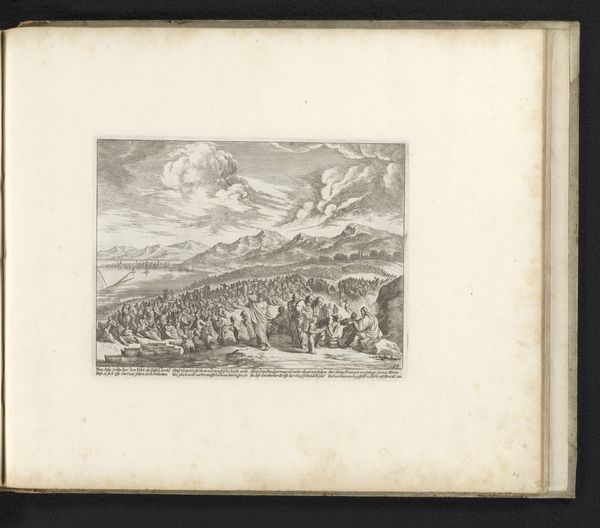

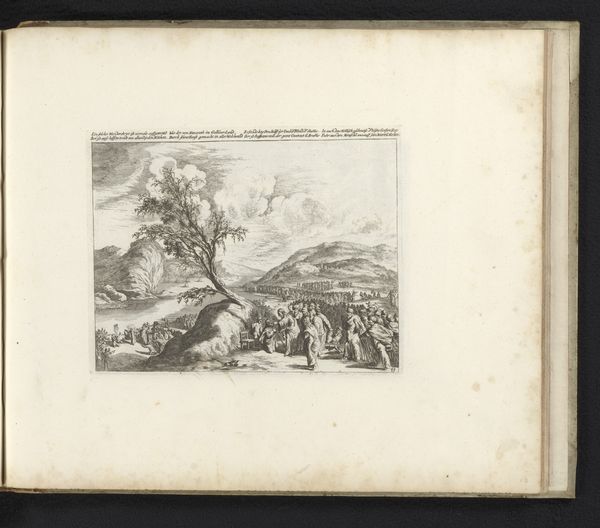

Dimensions: height 160 mm, width 206 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have "Intocht in Jeruzalem" (Entry into Jerusalem), a print made between 1670 and 1682 by Melchior Küsel, housed here at the Rijksmuseum. It's incredible the detail they achieved using just pen and ink. The entire scene has an energetic, almost chaotic feel. What catches your eye about this piece? Editor: The level of detail for a print of this scale is impressive, as you noted. I'm interested in the technique itself - what does the printmaking process contribute to the meaning here, as opposed to, say, an oil painting? Curator: Precisely. The use of printmaking implies reproduction and dissemination. It wasn't simply about depicting a scene, but about circulating it to a broader audience, which makes me think about the context of its production. Who was this print intended for and what was its purpose? Was it intended to simply represent the historic Jerusalem or make a theological claim about the historical importance of that space, through its wide dissemination? Editor: That's a great point about reproduction. Given the tumultuous period of religious reformation, the widespread distribution enabled by the printing process, becomes almost a political statement. Were prints like these easily accessible to common people? Curator: Absolutely. Prints allowed for relatively inexpensive distribution, thereby bypassing the traditionally wealthy patrons of the art world. Now, when you think about it that way, how does the seemingly classical representation style juxtapose against its means of production and its popular dissemination? Editor: So, it’s using an established artistic language – almost an ‘official’ aesthetic – to spread a message among the masses. I'm also curious, how does the materiality of the print—the ink, the paper—contribute to its meaning, compared to other, more ‘precious’ materials? Curator: Consider paper itself. In this era, it was becoming increasingly accessible but was still inherently fragile. Its affordability made knowledge and imagery more democratic. Does that maybe connect with a democratization of religion itself, through mass availability of the visual stories and their religious messages? Editor: That gives me a lot to consider about the piece. Thinking about the material and its access, you highlight how technique fundamentally reshaped consumption and its impact on 17th-century European culture. Curator: Indeed. By examining the labor and dissemination processes of the work we can gain far greater insight to it’s meanings.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.