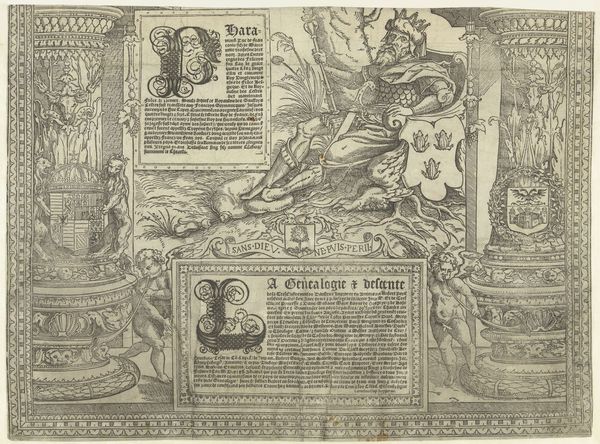

Mary, Queen of Scots with her son, James I, King of England, Scotland and Ireland 1573 - 1583

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 10 7/8 × 7 5/16 in. (27.6 × 18.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This print, “Mary, Queen of Scots with her son, James I, King of England, Scotland and Ireland”, dates back to somewhere between 1573 and 1583. It’s an engraving. The starkness of the lines and the way the figures are presented, almost like medallions, gives it a formal, removed quality. What strikes you when you look at it? Curator: I immediately see the process of production at play. Consider the material itself: this engraving on paper. It speaks to the rise of print culture and its ability to disseminate images and, importantly, narratives, much faster than paintings or tapestries. It brings into focus the material conditions of image making and the social context in which this artwork was consumed. We need to look into the networks through which such prints circulated and their affordability for the upwardly mobile merchant class. Editor: That’s a very interesting take! I hadn’t thought about the economics. Was this sort of accessible imagery considered “less than” traditional portraiture? Curator: Precisely! It challenges traditional boundaries between ‘high art’ and what was deemed craft or even propaganda. The engraving, through its relative affordability and reproducibility, became a tool of political positioning, offering wider audiences the crafted image, in this case the monarch. Who controlled the presses, and what narratives were they selling? That's what matters. How does this print function as a commodity in the developing political landscape? Editor: So, looking at it from this materialist perspective, it’s not just about who is depicted, but *how* it was made, distributed, and consumed. I see how thinking about those processes opens up a whole new level of understanding. Curator: Exactly. This image becomes a valuable artefact not just for its visual content but for what it reveals about the means of production and circulation in 16th century Europe.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.