Dimensions: sheet: 17.4 x 24.9 cm (6 7/8 x 9 13/16 in.) cut to platemark

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

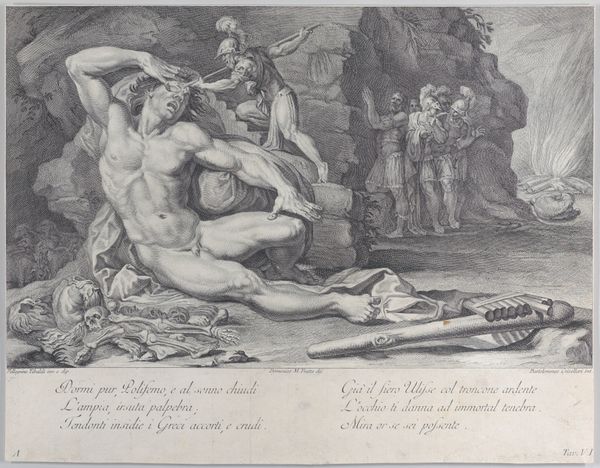

Curator: Here we have Hendrick Goltzius’ engraving, "Jupiter and Io," created around 1589. What strikes you immediately about this print? Editor: The density of the lines is the first thing. It almost feels like a swarm, or a woven fabric pulled tight. The artist must have spent an unbelievable amount of time incising those lines into the plate. Curator: Absolutely. Goltzius was a master printmaker and very active in disseminating classical imagery. This piece exemplifies Mannerist style with its dramatic composition. Consider Jupiter concealing Io from Juno, transforming her into a heifer to hide his infidelity. The eroticized image of Io is central to the visual narrative. Editor: It’s not just the eroticism. I’m fascinated by the means Goltzius employs here. Engraving is painstaking labor and demands incredible skill in material handling, using a burin to directly cut the plate for printing. Think about the economics of producing these prints. They made mythological subjects widely available, a commodity distributed for education and enjoyment, reinforcing class structure, though that very distribution eventually empowered wider access to knowledge. Curator: Precisely! Prints held immense cultural power in the late 16th century. The dissemination of images shaped social understanding, political discourse, and even religious identity, impacting both public and private spheres of life. Goltzius operated within this nexus of art, commerce, and power. Editor: It's a feedback loop between art, audience, and the techniques available. And, yes, that image of Io, all polished skin created from an insane density of etched lines…it speaks to how male desire becomes concretized through the labor process. Curator: And it reveals that such images were integral to maintaining a status quo concerning power and gender in early modern society. Art as propaganda, and beautiful, technically brilliant propaganda, at that. Editor: So, it’s more than just an image, right? It's labor, material, consumption, politics, all bound together. Curator: Exactly. Seeing this engraving means examining not just its beauty but also its historical impact. Editor: An image like this makes you think about who could access the subject of these mythological prints back then, and how the consumption and means of distribution served to perpetuate societal dynamics. Curator: Indeed. And it’s those connections which add such rich texture to the artwork's interpretation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.