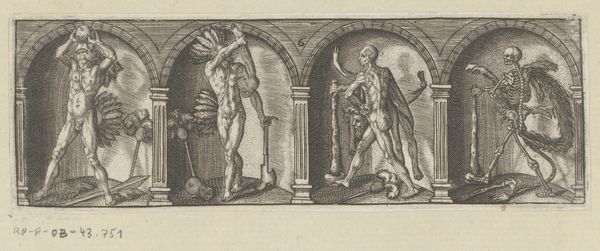

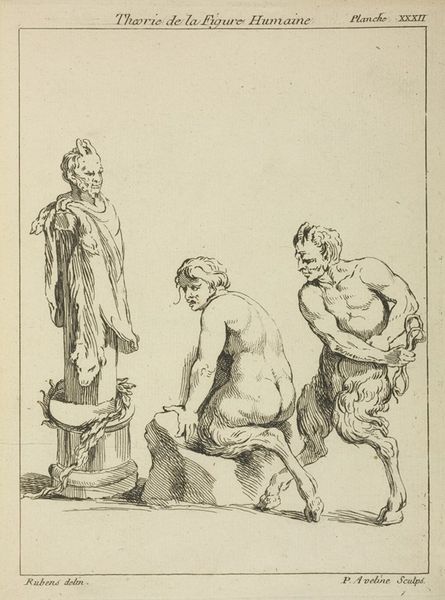

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 222 mm, width 316 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us is "Poenitentia," an engraving by Richard Collin, created in 1676. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It's stark, isn't it? Two nearly identical nude figures, rendered in that precise, linear style. One faces us, the other has turned away. There's something inherently vulnerable about the positioning, both revealing and concealing at the same time. Curator: Precisely. The duality is key to understanding the piece through the lens of its title: "Poenitentia," which translates to penitence or repentance. The front-facing figure seems almost childlike, invoking a sense of innocence lost, while the turned back implies shame or a turning away from something. Editor: I'm particularly struck by how these images were likely received within the artistic and social structures of 17th-century Europe. Consider the role of religious doctrine shaping ideas about sin, guilt, and redemption. Was this image designed to inspire piety, or something more critical of institutionalized religion? Curator: That's precisely the kind of discourse that informs a deeper understanding of "Poenitentia". We can’t ignore that in this era, depictions of the nude body, especially within a religious context, carried immense political and social weight. The figure isn't simply repentant in isolation. The composition and title directly address viewers—likely pushing against societal values. Editor: It's also hard not to notice that the style almost clashes with the thematics. The figures possess a sort of detached, idealized beauty that feels contradictory. Curator: Ah, yes, a contradiction we can pull into focus to enhance our knowledge, in part, by understanding how this relates to larger narratives around idealized beauty, guilt, and atonement that continue to influence artistic creation today. It highlights the complexities within Collin’s work, positioning him at the intersection of social commentary and traditional aesthetics. Editor: Considering the cultural milieu of the 17th century, works such as "Poenitentia" were created and consumed within a very defined ecosystem—one heavily influenced by patronage, academic institutions, and societal expectations. Its continued display in the Rijksmuseum certainly invites renewed debates on art’s purpose in the public space. Curator: Agreed. It compels us to ask urgent and perhaps uncomfortable questions regarding institutional structures in the arts as well as Collin’s own social, and quite probably ideological, positioning. Editor: The stark composition, almost clinical in its precision, pushes a conversation that’s less about simple admiration of the work and far more centered on the societal role of art and image creation itself. Curator: I walk away considering if this visualizes an enforced, perhaps unwanted, state of atonement.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.