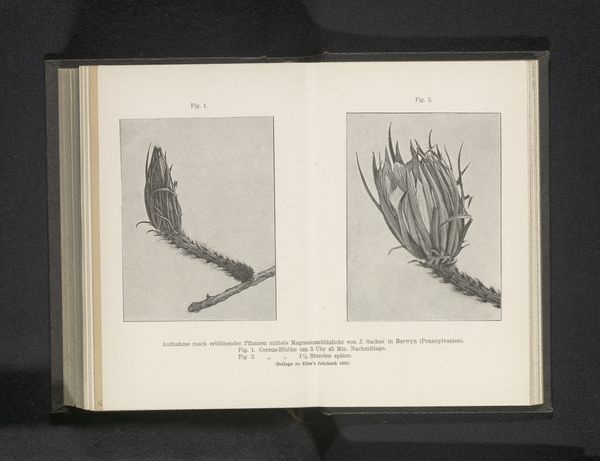

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

still-life-photography

# print

#

book

#

text

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

modernism

Dimensions: height 117 mm, width 91 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

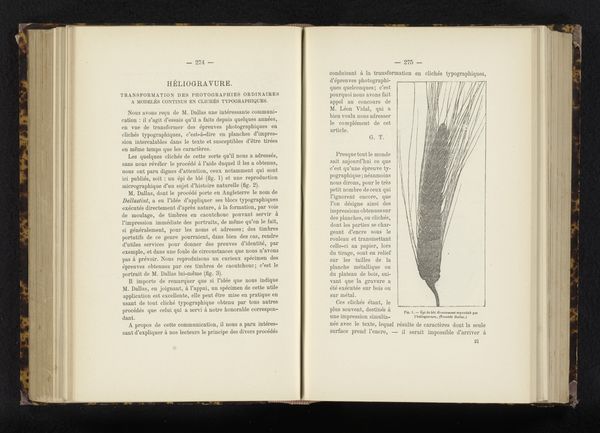

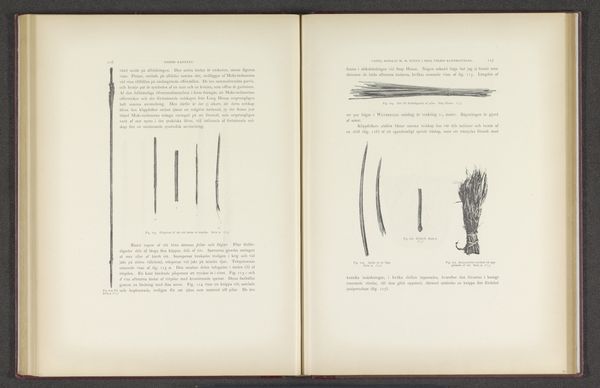

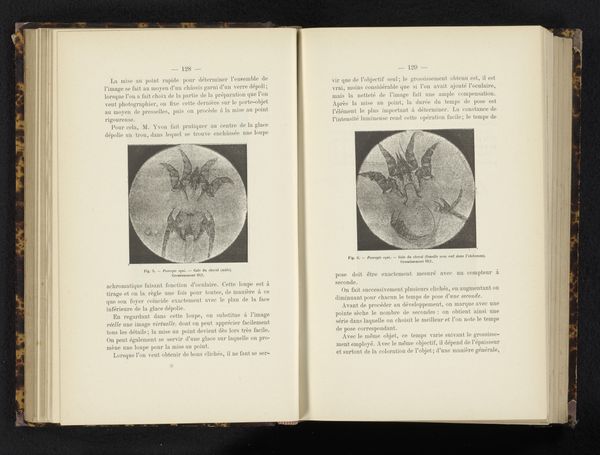

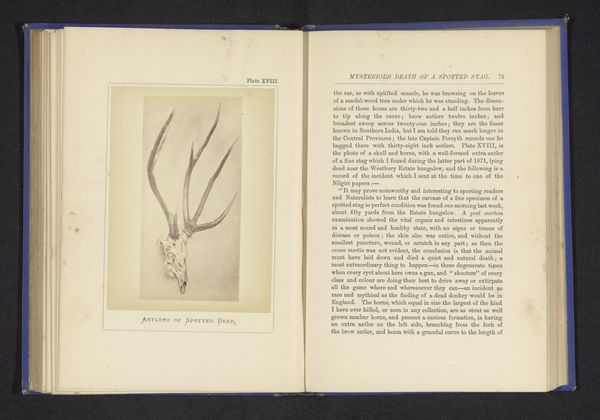

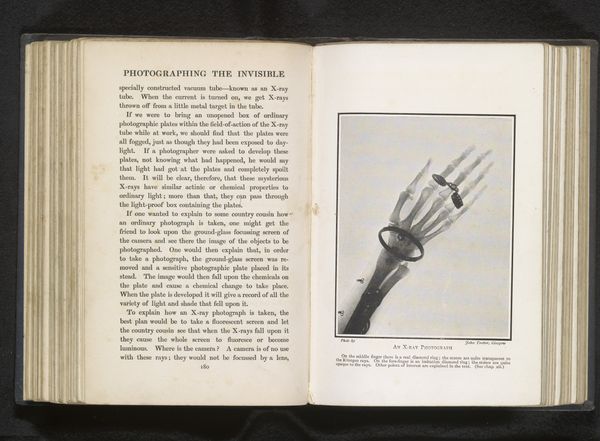

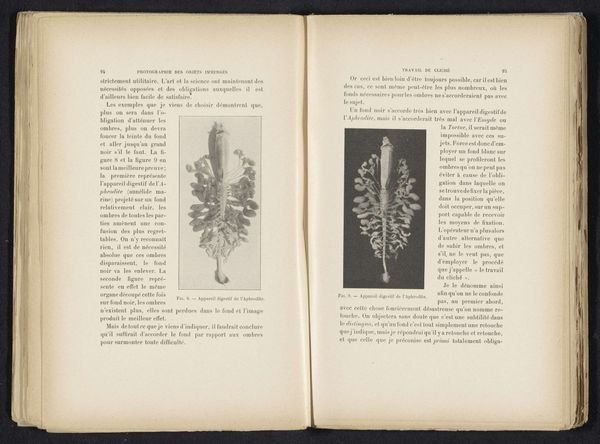

Curator: The arresting visual before us, entitled "Microscoopopname van een spinnenpoot," or "Microscopic image of a spider's foot," was captured before 1908 by Arthur E. Smith. Editor: I am struck by the stark contrast and ghostly ethereal quality of this photograph. It evokes both beauty and a touch of uncanny dread. Curator: Smith uses the gelatin silver print process, which became a popular method during that period for its tonal range and sharpness, lending a unique crispness to the image here, printed within the leaves of a book. Notice the stark, graphic arrangement—a modern visual sensibility. Editor: It's fascinating how a functional object like a spider's foot is transformed through the photographic process. I'm drawn to consider the labor involved in producing not only the photograph itself but the very construction of the knowledge contained within the book format, revealing the painstaking procedure for mounting specimens for photography. The tangible materials and techniques behind scientific documentation fascinate me. Curator: Precisely. This early example highlights photography’s transition into the scientific field. Smith transforms a potentially gruesome specimen into an exercise in abstract design, achieving dramatic tension between the detail and its minimalist, almost graphic form. Consider also the visual rhyme created with the adjacent page of descriptive text, amplifying the image through language. Editor: And doesn’t it challenge our very assumptions about art and the natural world? By isolating this minute detail and blowing it up to the size of an illustration in a book, the viewer can begin thinking of what sort of specialized technologies—the camera, the gelatin process, the microscope—were used to isolate and observe nature. I am interested in where we encounter an object’s physical labor and where we tend to ignore it, obscuring labor under the heading of technical progress. Curator: It also serves as a powerful reminder that unseen worlds—entire universes of intricate forms—lie just beyond our everyday perception. Editor: It's an opportunity, perhaps, to recalibrate our own perspective on labor in artistic production.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.