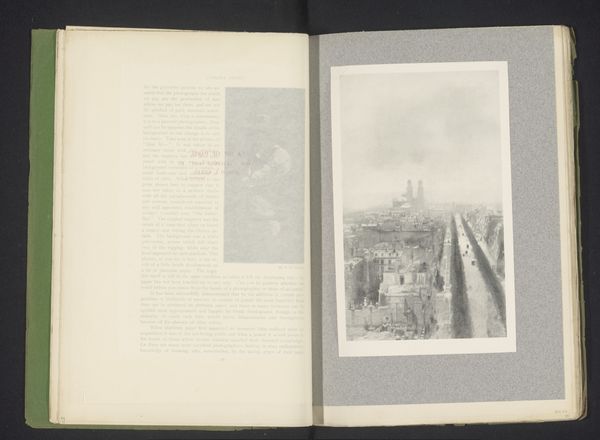

Gezicht op de Rue des Chenizelles en de Porte des Chenizelles in Laon, Frankrijk before 1896

0:00

0:00

print, photography

# print

#

photography

#

street

Dimensions: height 166 mm, width 122 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

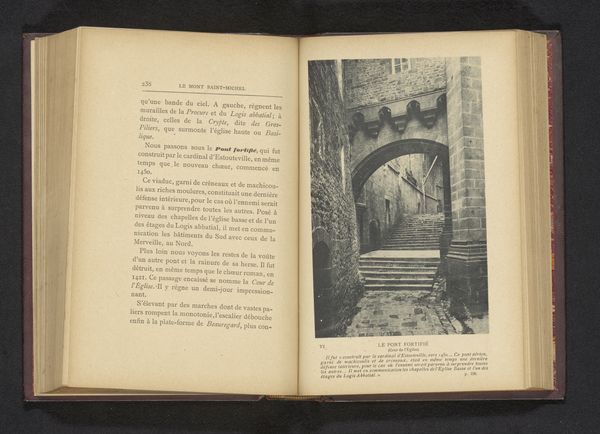

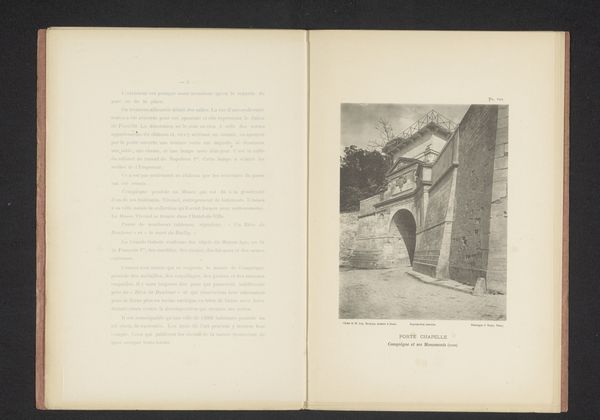

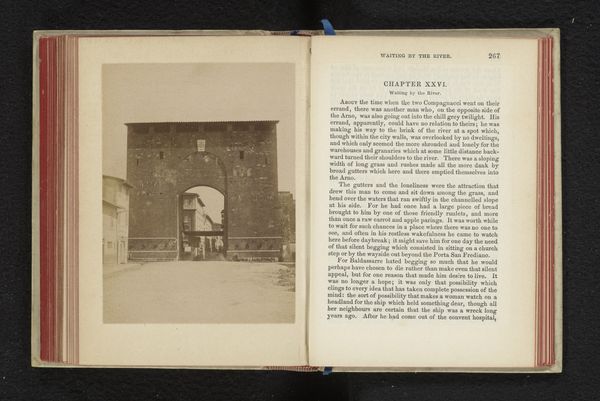

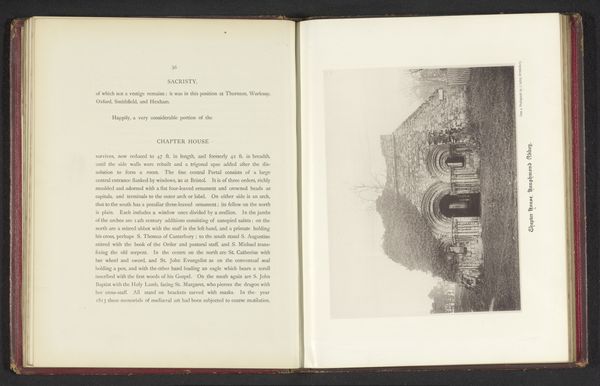

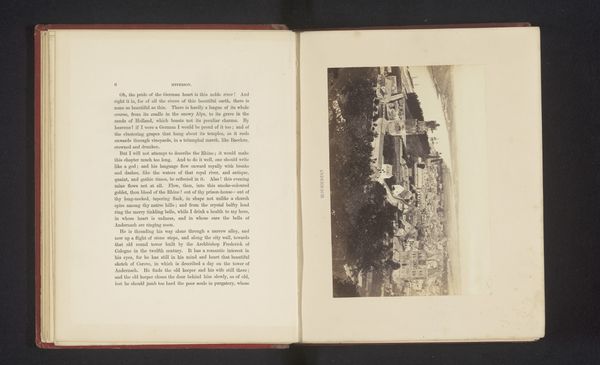

Curator: Let’s take a look at this print by Jules Royer titled "Gezicht op de Rue des Chenizelles en de Porte des Chenizelles in Laon, Frankrijk," created before 1896. It’s a view of a street scene in Laon, seemingly captured through photography then reproduced. What’s your first impression? Editor: It has such a palpable atmosphere. The light catches the rough stone so beautifully; you can almost feel the cool dampness radiating from the walls. And is that a figure leaning there on the right? He certainly lends to its stillness. Curator: That figure grounds it, doesn’t he? You sense the street's historical function, a passageway defined by monumental architecture. These gates acted as critical control points for entry, influencing trade, migration, and defense within the town. The figure hints at modern appropriation of old spaces, almost a quiet disruption. Editor: Disruption through leisure. Notice the textures—the meticulously laid cobblestones and the rough-hewn blocks forming the walls. What kind of labor would it have taken to build this? Consider the skills required not just for masonry but for shaping each individual stone. The walls have such permanence to their materials that speaks volumes, too, right? Curator: Absolutely. We also can't forget the process of image reproduction at the time, transforming photography into print to facilitate dissemination to broader audiences. So it is an interesting question how technologies interact and affect our viewing of spaces, as some voices believed reproductions destroyed “aura”. But maybe it made these sites, now removed by history, accessible in novel ways. Editor: I love the way the reproduction highlights texture and grain and celebrates materiality and structure; these features can take precedence, becoming celebrated features. Royer’s method almost creates a sense of democratisation here too, where form and design can become powerful and publicly accessed, no matter if that location has lost social position over time. Curator: It is quite interesting indeed when we consider art's complex dialogue with history and our modern reception of historical objects, seeing echoes of socio-political realities manifested materially and publicly. Editor: Agreed, It’s really amazing when processes can become such a tactile key for interpreting place and politics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.