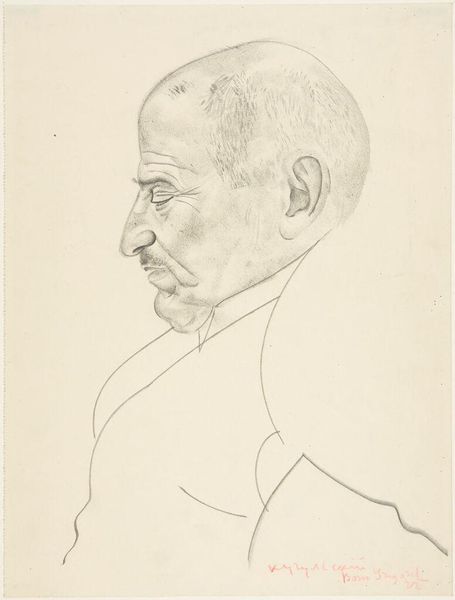

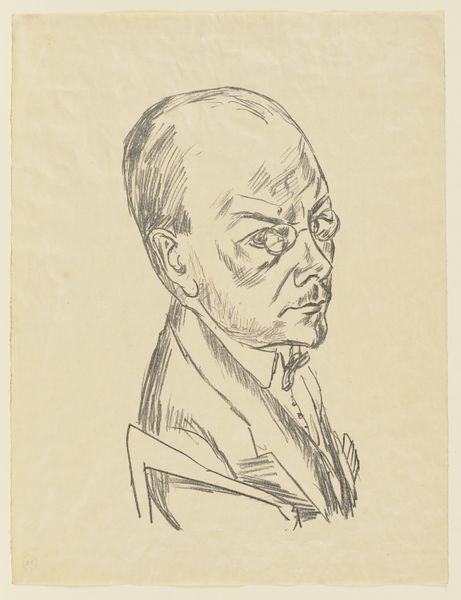

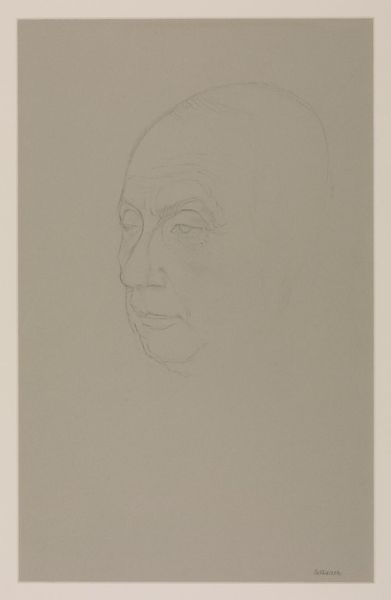

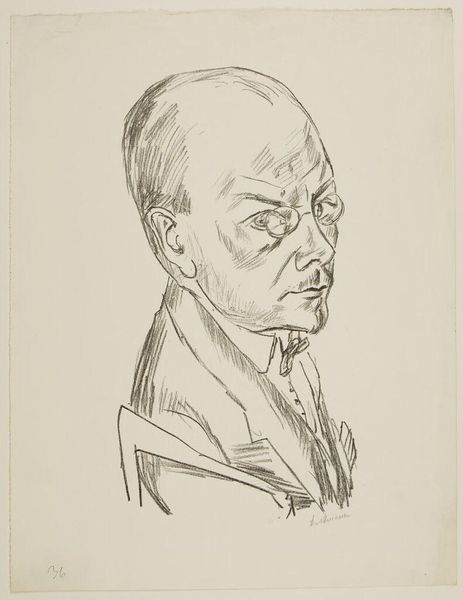

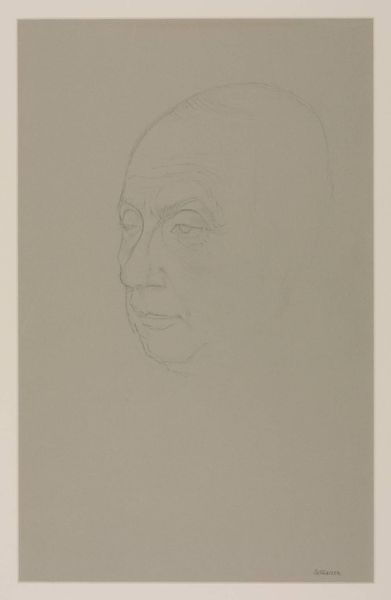

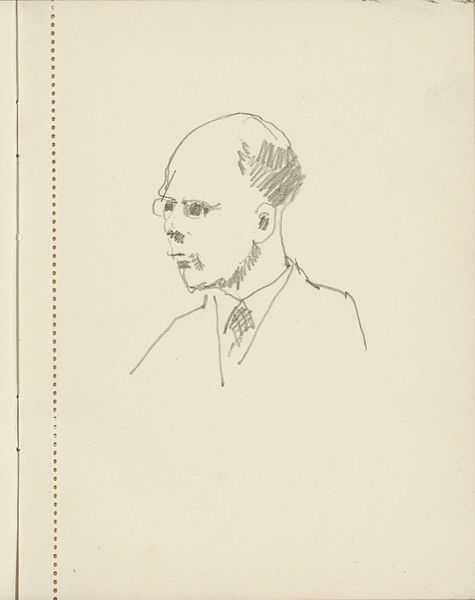

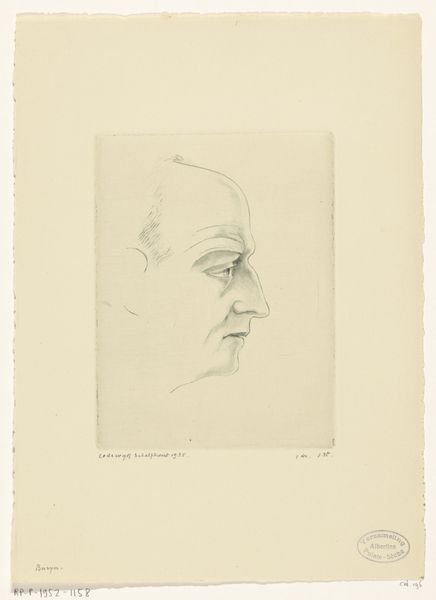

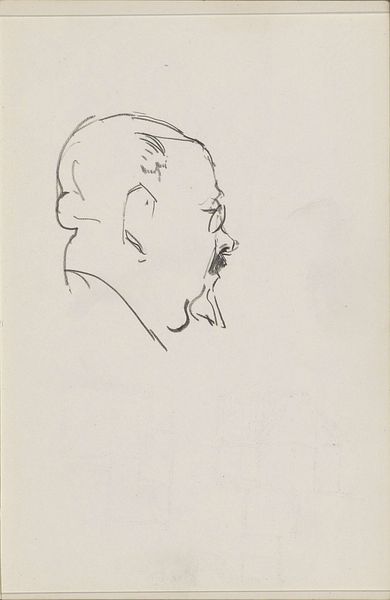

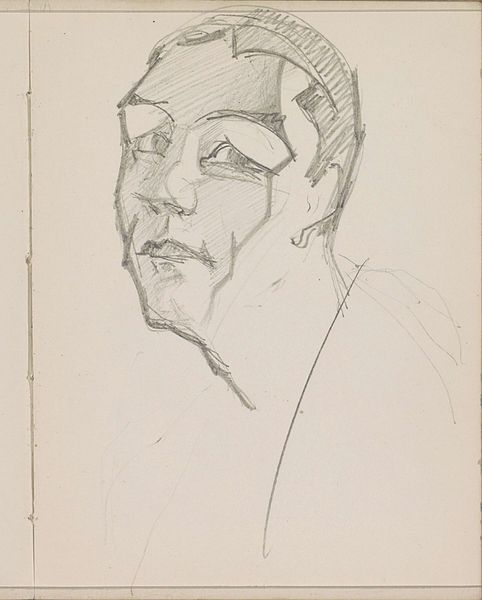

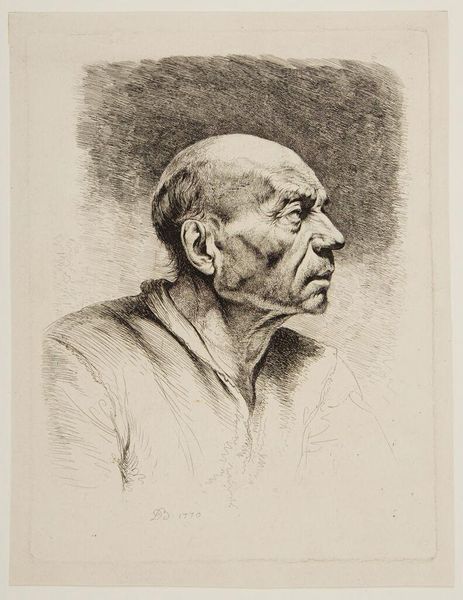

drawing, pencil, graphite

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

graphite

#

portrait drawing

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

Editor: Here we have Eero Järnefelt's "Omakuva," dating to the 1920s. It's a drawing rendered in pencil, almost like a study. It has a certain raw quality to it; the lines are visible, showing the process of creation. What strikes you about this work? Curator: Immediately, I'm drawn to the visibility of labor within the piece. Järnefelt hasn't obscured the graphite strokes or the initial sketched lines. This challenges the traditional idea of the artist as a distant genius, doesn’t it? We see the artist *working*. How might the availability and cost of materials, like graphite during this period in Finland, influence Järnefelt’s choice of medium and style? Editor: That's a great point. I hadn't considered the material constraints. So, the simplicity might be deliberate, but also economical? Curator: Precisely. Also, the concept of "Omakuva" or "self-image," which highlights artistic intention and the marketing surrounding this piece. In a materialist reading, even the artist’s intention becomes another layer of labor. How might the *reception* of such a visibly handmade work differ from that of, say, a meticulously finished oil painting of the time? Do you think it was aiming for broader appeal, being easier and cheaper to reproduce? Editor: I suppose that by revealing the means of production, Järnefelt is inviting the viewer to connect with his artistic practice. He's closing the distance between creator and audience through this medium. So by displaying labor so overtly, is he elevating 'low' art of drawing towards 'high' art? Curator: Exactly. The visible labor creates value, doesn't it? It invites scrutiny of its social context. Now that you have seen its relation to work conditions of the time, how do you reflect on this work? Editor: Seeing how the economics of materials and the open display of artistic labor shaped the piece gives me a much deeper understanding. Thanks for your help!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.