Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

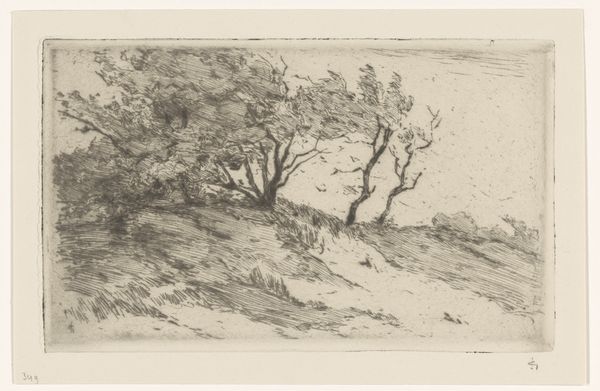

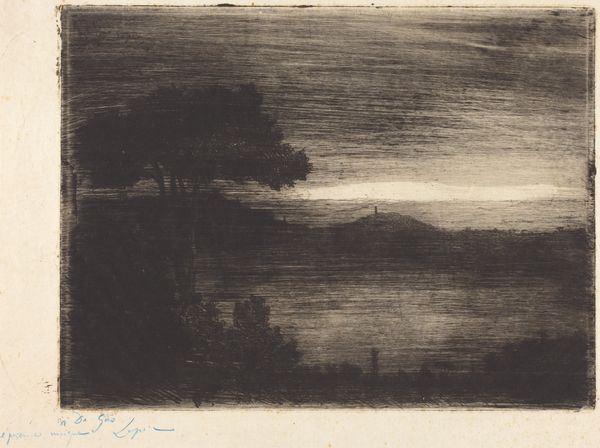

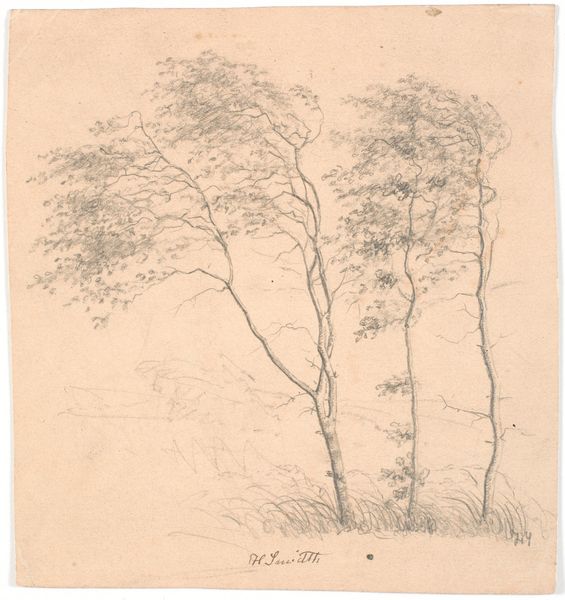

Editor: So, this is Trude Hanscom's 1952 etching, "The Tempest." I'm struck by how she uses line to convey such a raw and turbulent scene. What are your thoughts on how she created this? Curator: The etching process is critical here. Consider the labor involved. Hanscom likely used acid to bite into a metal plate, controlling the depth and thickness of the lines. This isn't just representation; it's a direct physical engagement with the material world to conjure this natural phenomenon. It invites reflection on how she, as the artist, labored to create this landscape, in comparison to how natural laborers of weather shaped the scene itself. What can that teach us about Hanscom's perspective on nature? Editor: That's fascinating. I hadn't thought about the labor aspect so directly. The print itself – the material object – becomes a record of that process. Does the edition number, 100/48, play into your Materialist interpretation? Curator: Absolutely. It forces us to think about reproduction, and the implications of consuming multiple iterations of the same image. Printmaking democratizes art, making it accessible beyond the elite, although the low number in the edition still suggest a limitation. But who are these for, and how are they distributed? Were they for teaching, commercial sale, or art-for-art's sake? Each would shift our understanding. Editor: I guess I usually focus on the imagery and what it "means" instead of considering that this is, like, a crafted object. Curator: Exactly. It’s not just an image, it’s a material document of a specific time, place, and mode of production, revealing a narrative about its creation and the social forces influencing it. Editor: I will never look at prints the same way. This helps understand the intersection of art, labor and consumption in landscape art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.