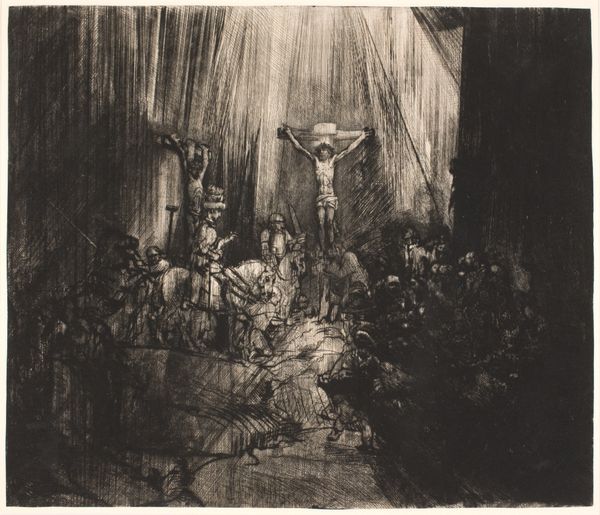

print, drypoint

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

drypoint

Dimensions: 15 3/16 x 17 11/16 in. (38.5 x 45 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

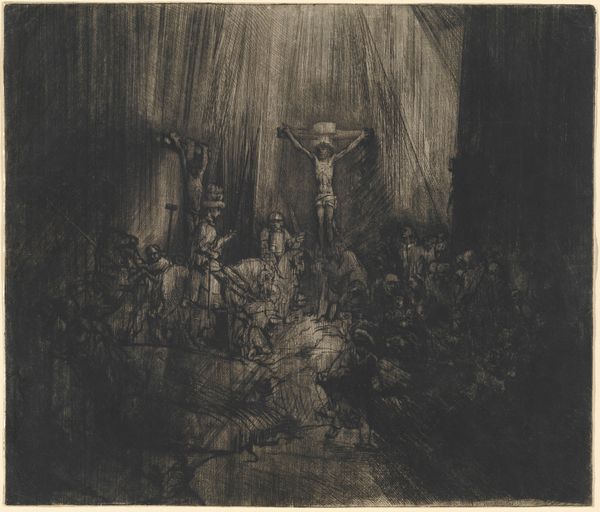

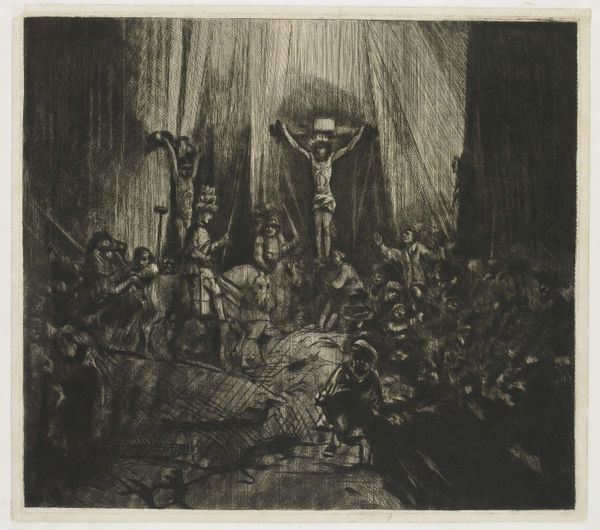

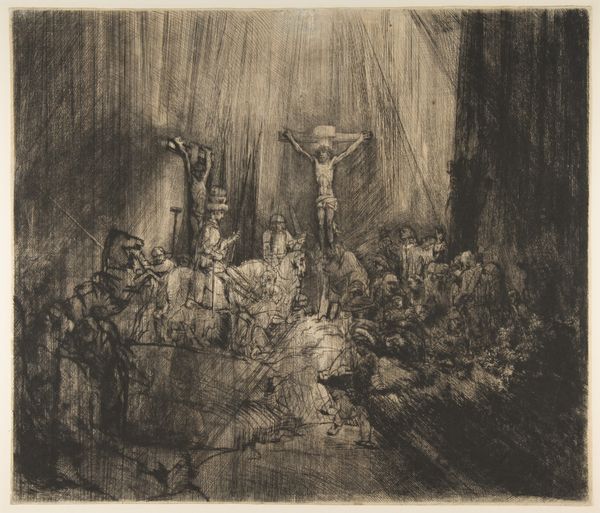

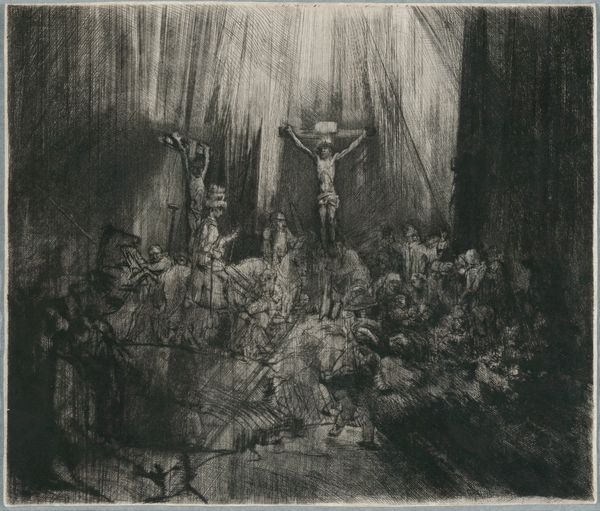

Editor: Today, we're looking at Rembrandt van Rijn's "The Three Crosses" from 1653, a print created using drypoint. The stark contrast of light and shadow is immediately striking, almost theatrical. It feels incredibly intense. What are your first impressions of this piece? Curator: It hits you in the gut, doesn't it? Rembrandt wasn’t just illustrating the crucifixion, he was *feeling* it. Imagine the scene, this single moment frozen. He creates such an emotional resonance through that dramatic use of light. Think about stage lighting—all the characters are on display! It makes you ask why these people? What are they feeling? It is Baroque storytelling, but without all the fancy bells and whistles we expect from a Baroque art piece. Do you agree? Editor: Yes, it does, but why this medium to convey emotion, couldn't he have used paint and convey that? Curator: Well, drypoint is a very direct medium, the artist is essentially scratching into the plate which is a slow deliberate mark. Also prints meant the work was easily circulated. So you feel he made a deep, deliberate, and ultimately reproducible artwork for mass distribution so more people could get in on the suffering? Editor: That's a fair point, I mean, everyone at some point will deal with it! Curator: Exactly. But I wonder how much the average 17th-century art lover would have connected that sense of suffering to their lives. Or did Rembrandt just corner the market of depicting suffering? Editor: Either way, this drypoint certainly offers a space for our collective pondering. Curator: True, art and the artist working together for the "greater" something something. Well thanks for making me ponder the collective human experience today. I certainly enjoyed it.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Rembrandt's grand interpretation of the Crucifixion probably developed in tandem with his Christ Presented to the People. It started out as an operatic extravaganza performed in a radiating cone of light. Rembrandt's revision of the Crucifixion scene was even more radical than his obliteration of the crowd in the judgment scene. He changed many details of the image. The horse in the earlier version has been reversed and received a rider in this later one. The centurion no longer looks up at Christ; instead, he bows his head in remorse. But most dramatically, Rembrandt took his etching needle firmly in hand to lacerate the printing plate, throwing the scene into chaos and darkness. He had never executed anything like this before or after. In fact, nothing would truly compare until the advent of expressionist art in the 20th century.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.