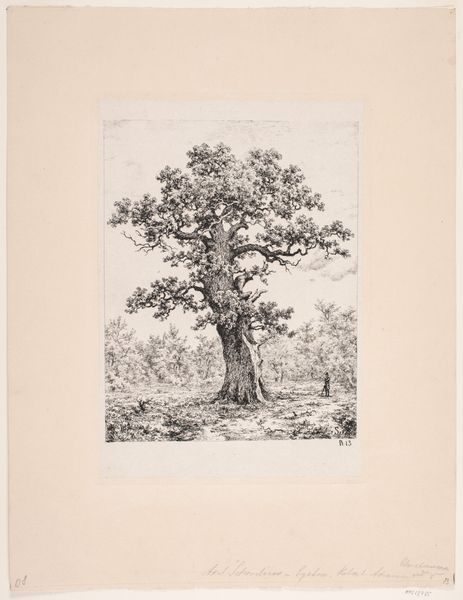

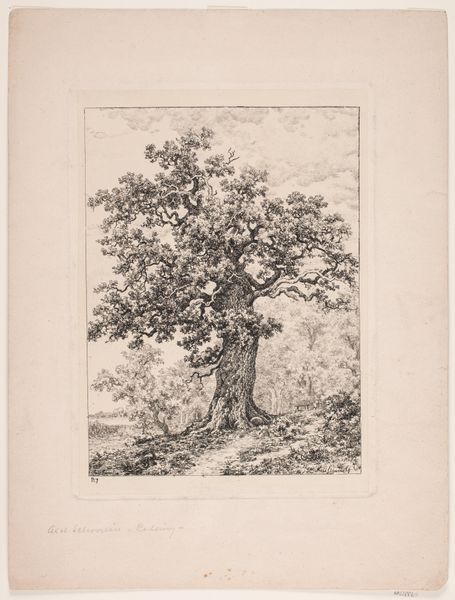

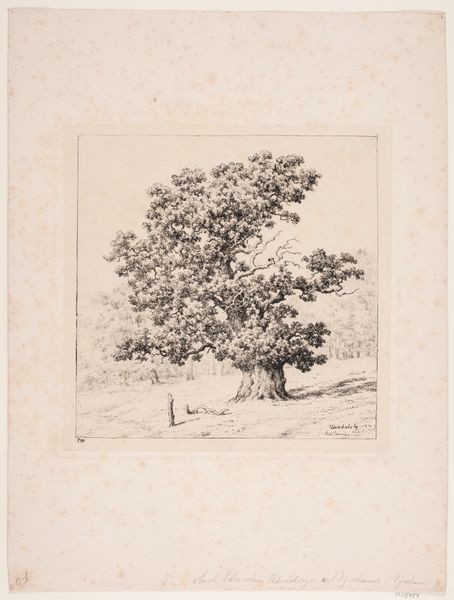

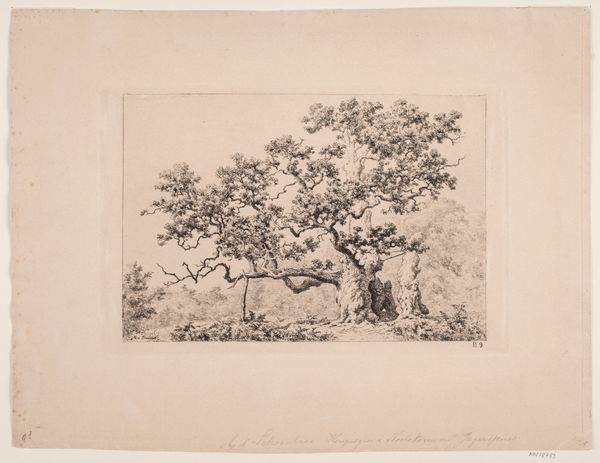

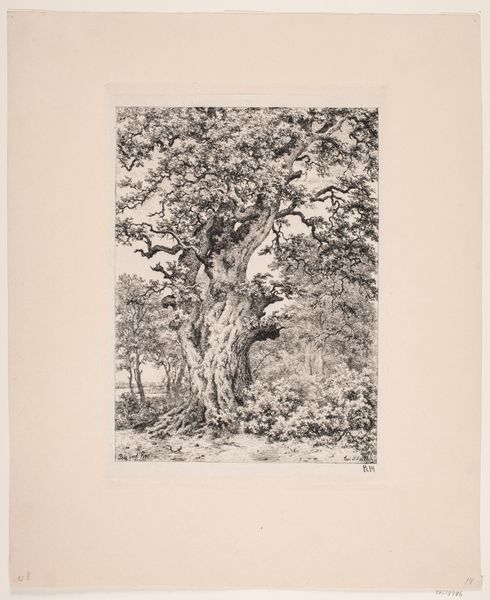

drawing, print, engraving

#

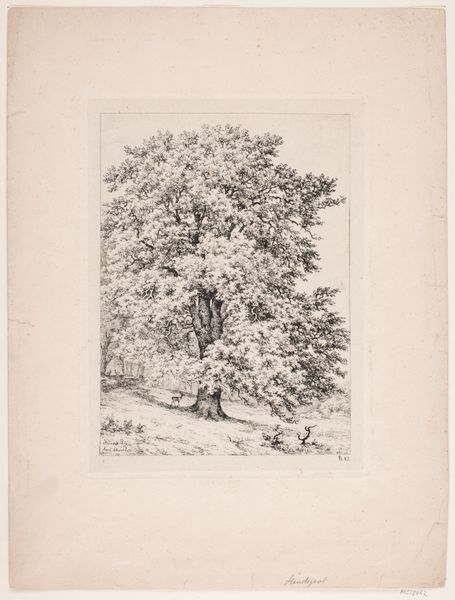

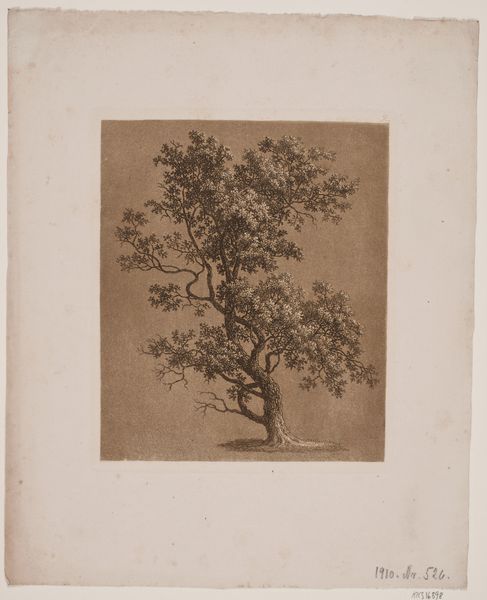

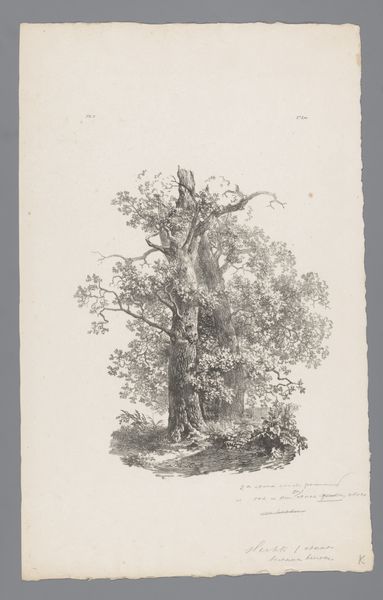

pencil drawn

#

drawing

# print

#

landscape

#

pencil drawing

#

line

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: 238 mm (height) x 170 mm (width) (plademaal)

Editor: So, this is Axel Schovelin’s “Frederiksborgegen,” made around 1880. It’s a drawing and print, and the detail is amazing. I'm really struck by the stark contrast between light and shadow; it makes the landscape feel both grand and a little melancholic. How do you interpret this work? Curator: It’s fascinating to consider the rise of landscape art within the broader context of 19th-century nationalism. Landscapes like this weren’t just about representing nature; they were actively constructing a sense of national identity, particularly for Denmark. Notice how the imposing oak dominates the composition, its roots firmly planted. Does that suggest anything to you? Editor: I guess it projects strength and permanence… maybe even Danish identity rooted in the land? It feels like it's glorifying a particular view of Denmark, though. Curator: Precisely. And consider who was consuming this art. It wasn't for the working classes. Prints like these were accessible to the bourgeoisie, helping to cement a specific image of the nation and reinforce existing social hierarchies. Think about how the castle Frederiksborgegen might factor into their perception of national history and power too. Editor: That’s a great point. It’s easy to see this just as a pretty landscape, but there are deeper layers of social and political meaning. I never considered how art could actively shape national identity! Curator: Exactly! By understanding the social forces at play during its creation and consumption, we see this seemingly simple landscape for what it truly is: a carefully constructed piece of national iconography. Editor: This really makes me look at landscape art in a new light, not just as pretty scenery but as part of a broader historical narrative. Curator: Indeed. The politics of imagery is ever present; awareness is key to understanding art’s function in the world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.