drawing, print, etching, pastel

#

drawing

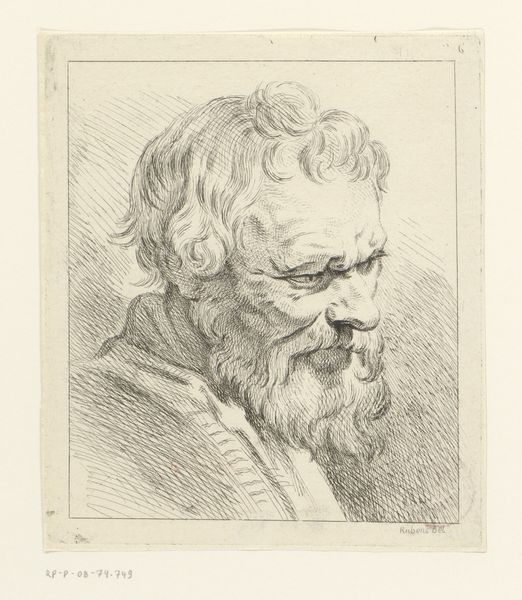

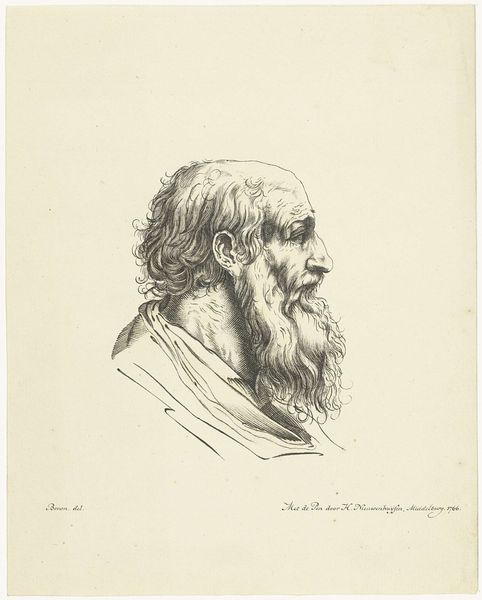

# print

#

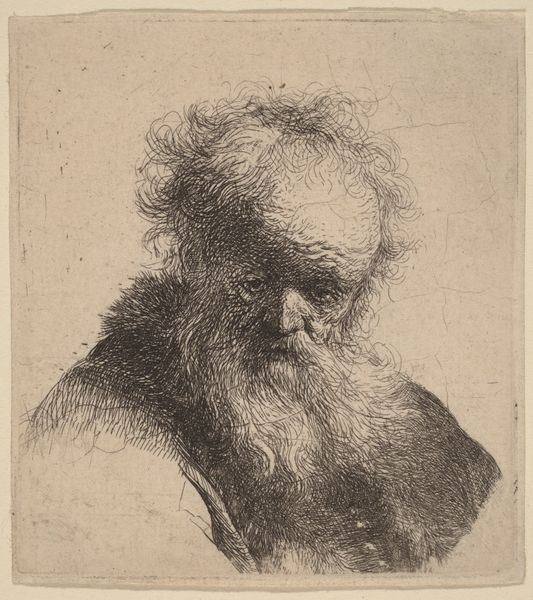

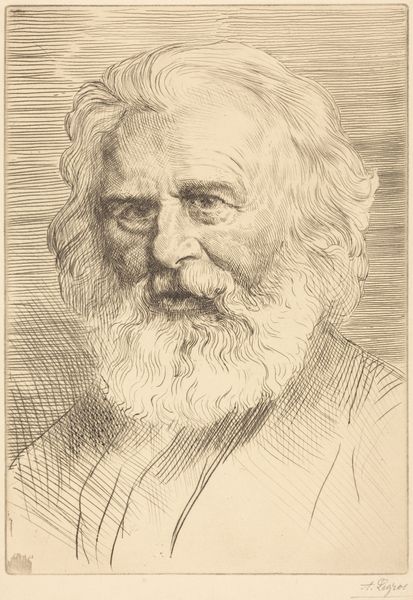

etching

#

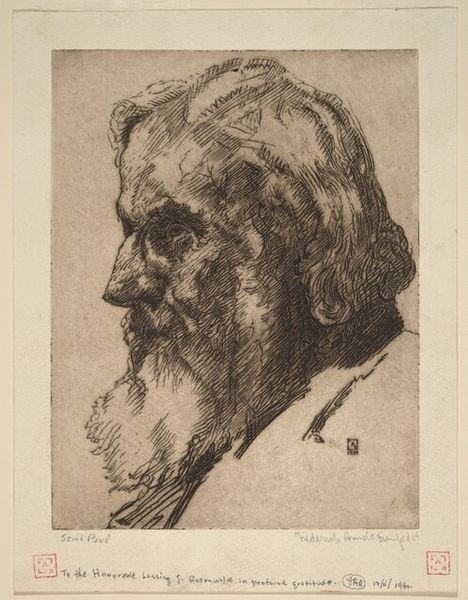

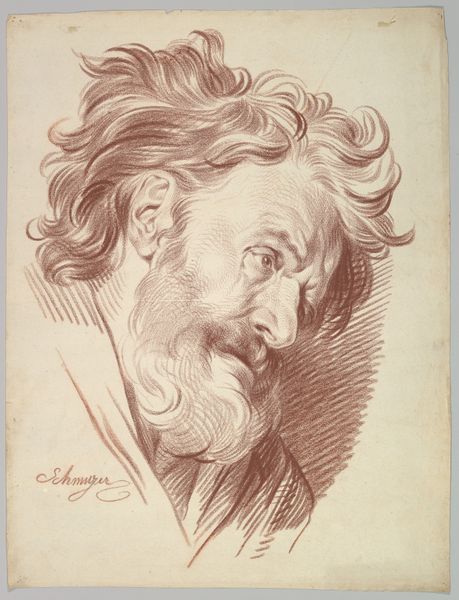

pencil drawing

#

portrait drawing

#

pastel

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

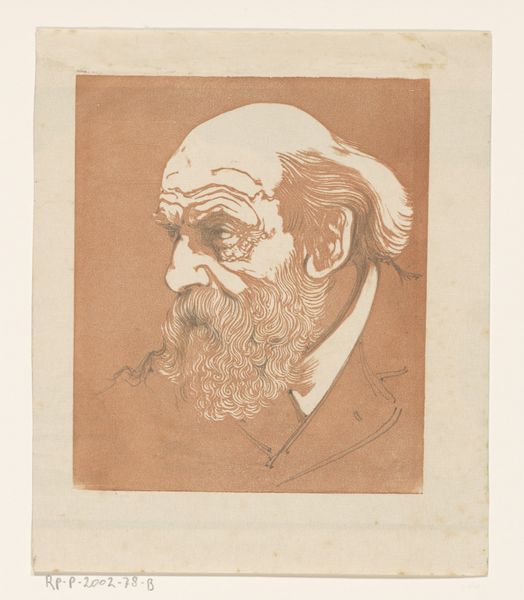

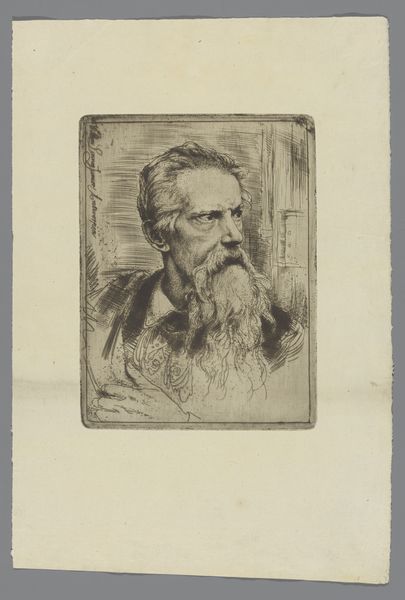

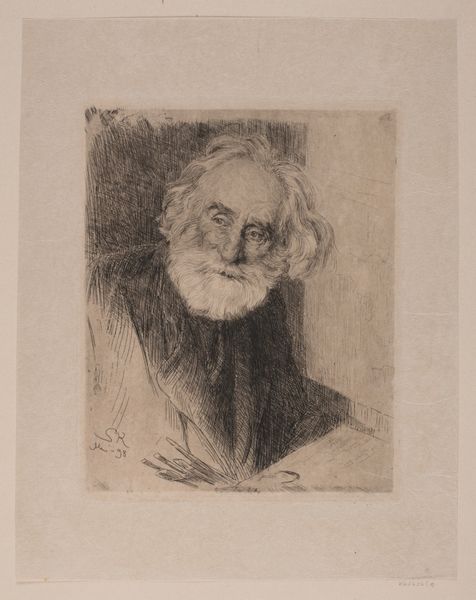

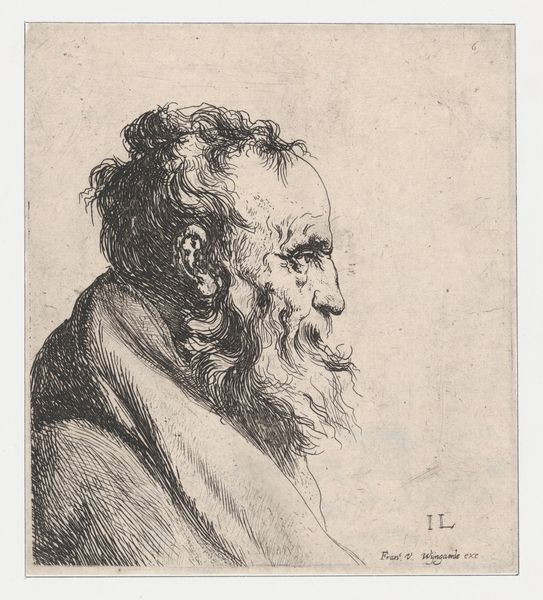

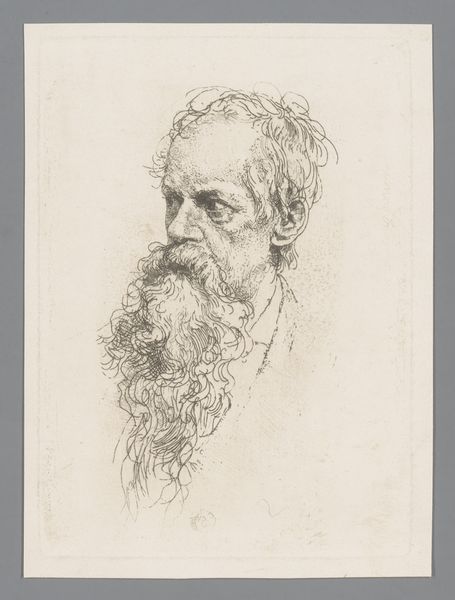

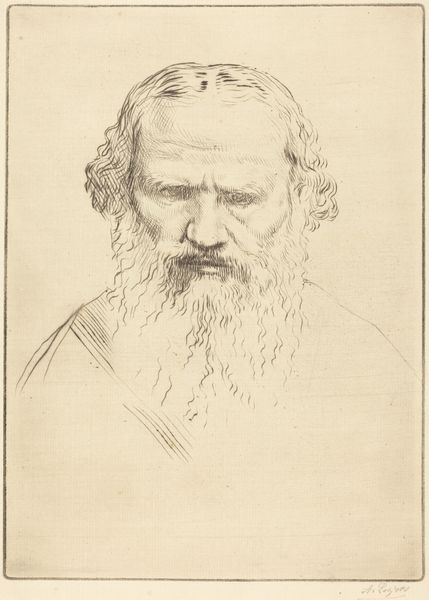

Dimensions: 208 mm (height) x 157 mm (width) (plademål)

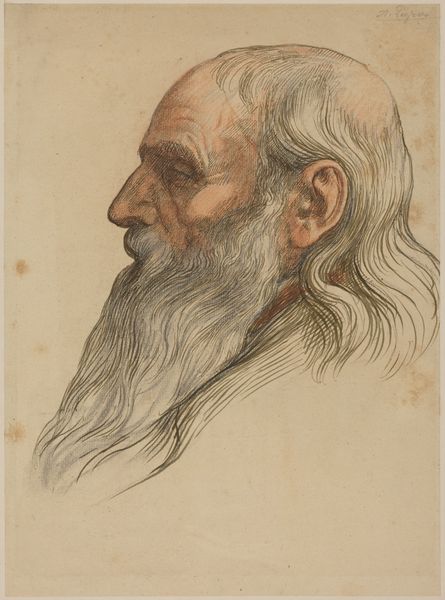

Curator: This drawing, "Portræt af en gammel mand en face," offers us a study of an old man's face by Louise-Rosalie Hémery, created sometime between 1775 and 1779. It is a red chalk drawing, a technique which lends itself well to the warmth and detail visible here. Editor: It strikes me as intensely human. The redness, as you point out, is key, giving a sense of warmth, vulnerability. His gaze is both wise and weary, and the marks of time etched so plainly feel really intimate. I find that compelling. Curator: Indeed. There’s a rich symbolism present. The aging figure is often a vanitas motif, prompting contemplation of mortality and wisdom gained through life's journey. The frontality is notable too, commanding attention. Editor: The question, for me, then, is what does this contemplation of mortality mean? In the 18th century, ideas around age and wisdom were so steeped in power dynamics, who was considered wise, who got to interpret that for the rest of society. Does this challenge or reinforce that hierarchy? Curator: Perhaps a little of both. Hémery uses academic art traditions. She shows that mastery of the art allows her to create this depth, but that depth lets her hint at themes beyond just skillful mimesis. His expression is open for the viewer’s projection, becoming something of a mirror reflecting their own understanding of aging and experience. Editor: A mirror… and perhaps a skewed one? Think of all the countless portraits that depict youth as ideal—portrayals that are then endlessly held against women as their bodies naturally change with time. I have to consider that here too. Curator: That's a very valid point. Hémery gives us this counterpoint by emphasizing wisdom in age. This drawing may invite reflection on beauty standards within a deeply gendered social context, though without offering a concrete revision. Editor: Well, no artwork can carry all the answers. What’s so good here is it’s a start—a starting point to raise these conversations even now, centuries later. Curator: I concur; perhaps that's why it remains so emotionally available. Its value lies as a vehicle of emotional engagement with a tradition while creating new associations with history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.