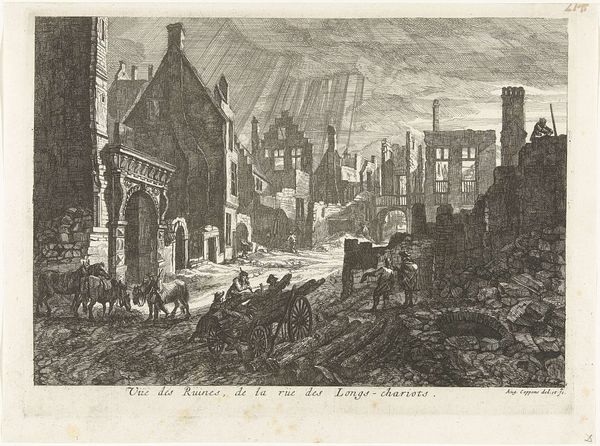

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 165 mm, width 198 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Pieter Schenk's "Ruins at the Grasmarkt in Brussels, 1695," an engraving likely made between 1695 and 1711. It depicts the aftermath of what appears to be a devastating event, possibly a fire. I’m struck by the detailed rendering of the destroyed architecture and the figures picking through the rubble. How should we approach interpreting a piece like this? Curator: Given that Schenk made a print, an easily reproducible medium, of the ruins, it raises interesting questions about accessibility, labour, and consumption. Was this print intended as a historical record, a form of disaster tourism, or something else? Consider the material conditions: the physical labor involved in creating the engraving plate, the cost of paper, and the social class that would have been able to afford such an image. Editor: That’s fascinating, framing it in terms of material production! It pushes me to reconsider the print's social value. The engraving shows workers amidst the rubble. Does their presence further highlight labor in relation to materiality and the creation of this piece? Curator: Absolutely. Note how the depiction of labor, typically downplayed in "high art," becomes central here. They’re not simply anonymous figures, they're actively reshaping the landscape, recovering and potentially reusing the materials. Schenk might be commenting on the cyclical nature of destruction and reconstruction, with labour as the engine. Are they erasing the previous city to build a new one, perhaps repeating mistakes, as laborers tend to do within class struggle and capitalism? Editor: It seems this is about far more than simply remembering the event or Baroque art. It points to questions about production, ruin, class, and rebuilding – and asks, “Who does that labor actually serve?" Thank you for directing me in a such compelling direction of material context. Curator: Indeed, it transforms the scene into a landscape of production and questions about who bears the brunt of destruction, and for whom does reconstruction happen.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.