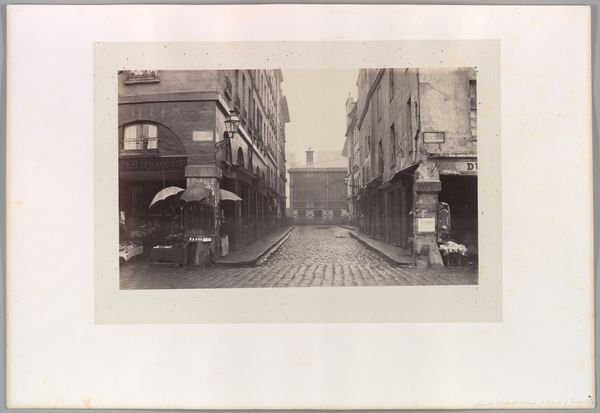

Dimensions: height 194 mm, width 138 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

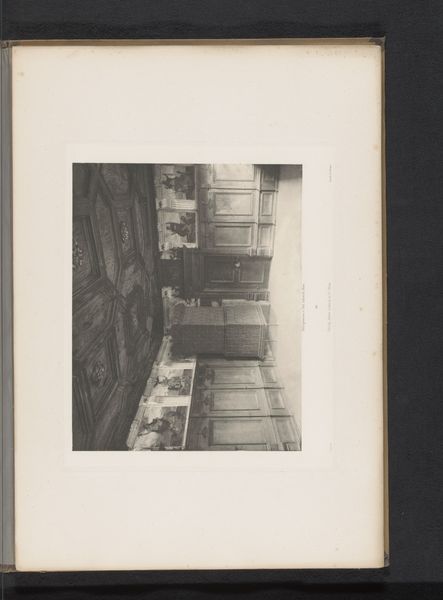

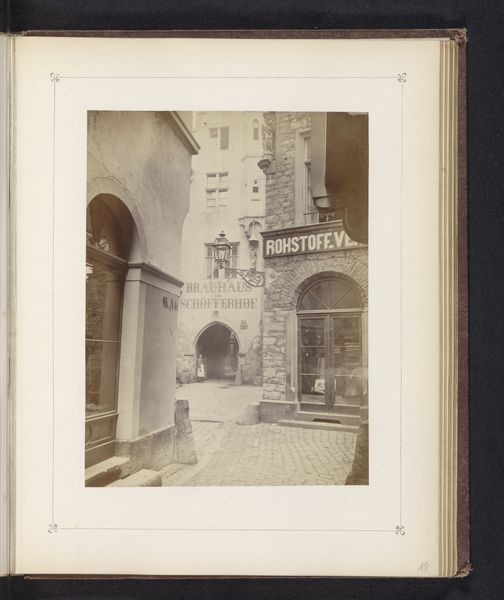

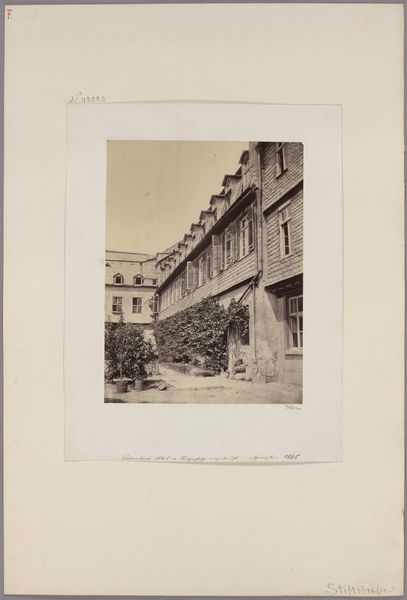

Curator: This gelatin-silver print, taken before 1869 by John Harrington, presents a view of Westminster Abbey, catching a quieter angle away from the bustle, shall we say? Editor: My first impression is that it looks like an illustration from a Gothic novel, all shadows and towering stone, very austere and even haunting somehow. The photographic process really captures the granular texture of everything, down to the cobblestones. Curator: Indeed. Harrington's "Gezicht op Westminster Abbey" translates from Dutch to “View of Westminster Abbey," but it also points to something beyond mere visual record. There’s a stillness that suggests timelessness. Think of the labor—quarrying the stone, carving those intricate details we see fading here, and, later, the photographer meticulously coating the plates with chemicals, composing the shot. It's an enormous amount of labor frozen in a moment. Editor: Exactly! That stillness clashes with the inherent busyness embedded in its making. And look how the different types of paving stones create an oddly graphic ground. Almost like proto-modern abstraction right there in front of us! Then you factor in the developing process: the solutions, paper, the darkroom practices... photography has its own peculiar relationship to labor and making as well. Curator: And think of who gets remembered. Here is this grand architectural structure representing power, authority, and centuries of history depicted by the lens of someone like John Harrington. His vision, his choice of perspective. And what was his motivation to make it and immortalize a fragment of an even grander idea. The material process and social act is what binds them. Editor: It does raise that important question of authorship. Is it Harrington's "creation," a collaborative venture between the photographer and all who constructed the space, or simply a document of existing labor and power structures? It makes you wonder about the untold stories behind those weathered stones. Curator: A wonderful provocation to end on, focusing less on pure aesthetics and more on layers of human experience that comprise an artwork. Editor: Indeed. Art, when understood materially, really throws light onto who built our world. Or should I say, worlds.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.