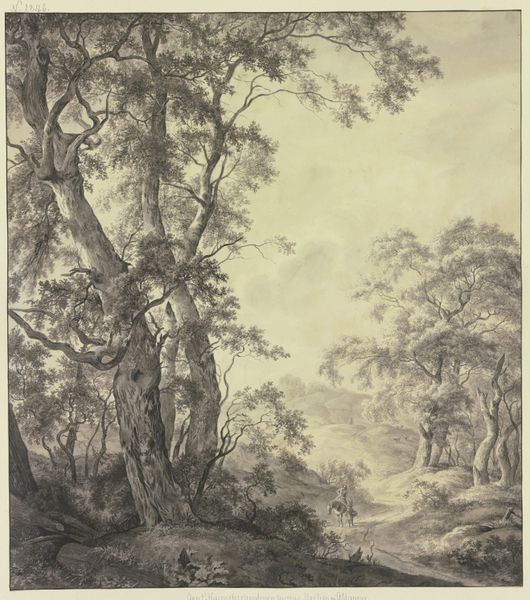

Landscape with a House Hidden Between Trees and Two Men Near a Small Bridge 1779 - 1808

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, paper, pencil

#

drawing

# print

#

landscape

#

paper

#

romanticism

#

pencil

Dimensions: sheet: 14 x 13 1/2 in. (35.5 x 34.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Just looking at this work gives me a deep breath of…grey. It's somber. Editor: I agree. Let's dive in. We are looking at a piece by Franciscus Andreas Milatz, "Landscape with a House Hidden Between Trees and Two Men Near a Small Bridge," made sometime between 1779 and 1808. It’s currently housed here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It appears to be primarily crafted from pencil and printed on paper. Curator: Immediately, the symbolism of nature overwhelms everything. The trees aren’t just trees. They are gnarled figures guarding a secret space. That house tucked in the background feels like a mental projection, a place of hidden longing. Editor: Fascinating take! I see the house more as an artifact, a constructed space built with timber and labor. Think about the act of procuring materials and raising this building, especially considering the pre-industrial period when the artist was working. Curator: The Romanticism oozes from every drawn line, and that path cutting through the forest leads the viewer’s eye—and hopefully their spirit—into the depths. The figures feel like surrogates, urging us to embrace the sublime melancholy of existence. Editor: Interesting…For me, the rough-hewn bridge dominates, reflecting on material realities. Who built it? What kind of tools did they employ? Were they members of the household that owns the space or itinerate construction laborers? Those pencil lines describe labor but also the local geology from which this timber comes from. Curator: I do concede the bridge is essential, a metaphorical threshold between the mundane and the transcendent, which are central concepts in Romanticism. It emphasizes humanity's fragile connection to the overwhelming force of nature. Editor: So you’re arguing that in this particular instance the symbol is itself materially formed? Fascinating. Considering Milatz was employing readily accessible materials, we could also question the nature of art consumption at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries. Curator: Yes! And that accessibility strengthens the visual narrative, empowering the audience to interpret personal meanings from its iconic language. Well, I've really enjoyed considering all these different dimensions of symbolic construction and the human drive for meaning-making with you today! Editor: Likewise. It's enlightening to engage with this landscape through multiple perspectives, underscoring both art as labor, and also the cultural and socioeconomic environment in which the artistic process occurs.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.