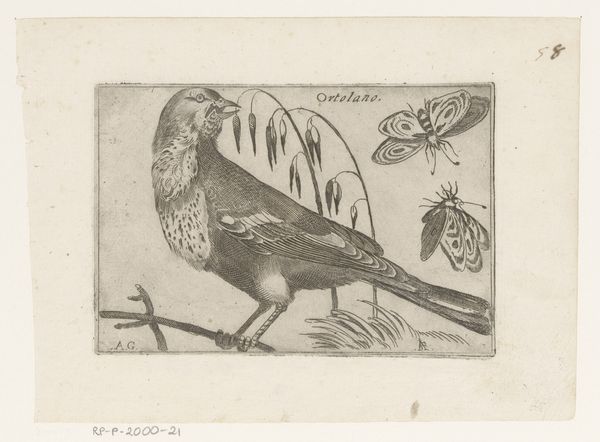

print, engraving

#

animal

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

11_renaissance

#

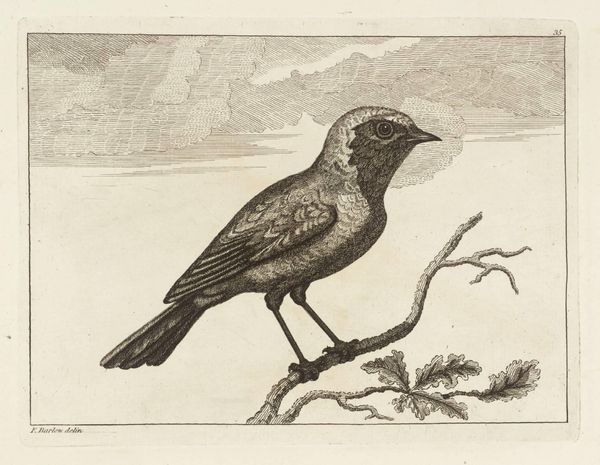

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 91 mm, width 135 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have an engraving from the late 16th century titled “Spreeuw (Sturnus vulgaris)”, or Starling, dating from around 1580-1590. It's currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection. The print is attributed to Jacques de Fornazeris. Editor: The somber yet meticulous rendering creates a melancholic stillness. There is an austere precision, in how Fornazeris captures the texture of the bird's plumage against the flat expanse of the engraving medium. I’m also interested in the way this realism sits alongside the decorative addition of a butterfly—are we supposed to find a kinship between them? Curator: Well, focusing on form, it is an astute study of contrast – the density of line creating the bird’s form plays against the negative space inhabited by the butterfly. Consider the engraving technique itself; the incised lines not only delineate shape but evoke the almost tactile quality of feathers. De Fornazeris expertly utilizes line variation to generate depth and shadow, all within a rigorously controlled composition. Editor: It strikes me that these Renaissance studies of birds occurred during an early moment of global encounter and colonization. The rigorous categorization that attends scientific illustration has troubling roots in the appropriation and classification of people during that same historical period. One has to wonder: who, precisely, did access to knowledge production around the natural world serve at this time? Curator: That may be so. But I think the artist is making specific visual decisions within a symbolic structure; the contrast isn't accidental, it establishes the very real weight of existence, embodied by this bird, within an overall structure of beauty. Notice also, the detail with which the Starling is rendered in comparison with the relatively light representation of the butterfly. These things are deliberate visual devices. Editor: Sure, there's intent on a formal level. And as always with visual language, who has access to it matters greatly. For some, this could serve as simply decorative—a symbol of erudition; but for others in the rapidly expanding, brutal colonial outposts, it must have been another expression of forced and extracted labour to further expand access to knowledge for Europe's powerful elite. It reminds us to engage critically. Curator: A pertinent reflection, indeed. Engaging with the art object, even one as apparently simple as this print, necessarily activates multiple modes of inquiry. Editor: Precisely, and keeping in mind how the tools we use for decoding the past, whether structural or historically contextual, necessarily impact our present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.