drawing, print, etching, paper

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

charcoal drawing

#

paper

#

charcoal

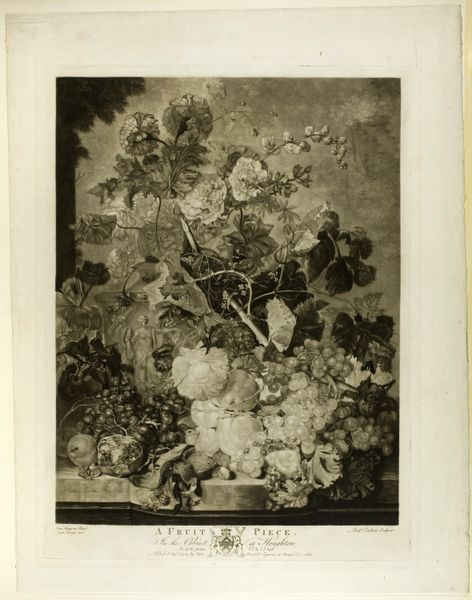

Dimensions: 503 × 394 mm (image); 552 × 426 mm (plate); 667 × 509 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

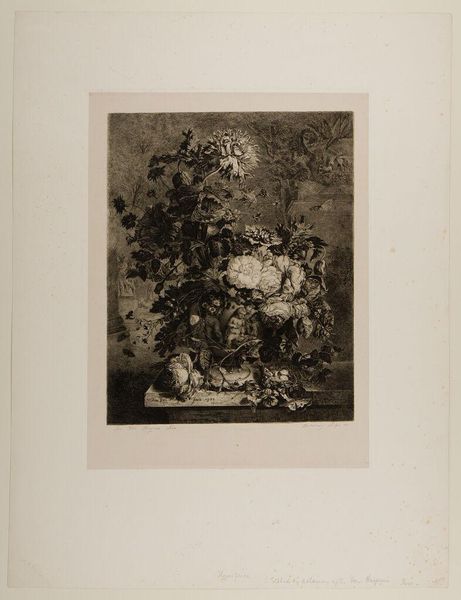

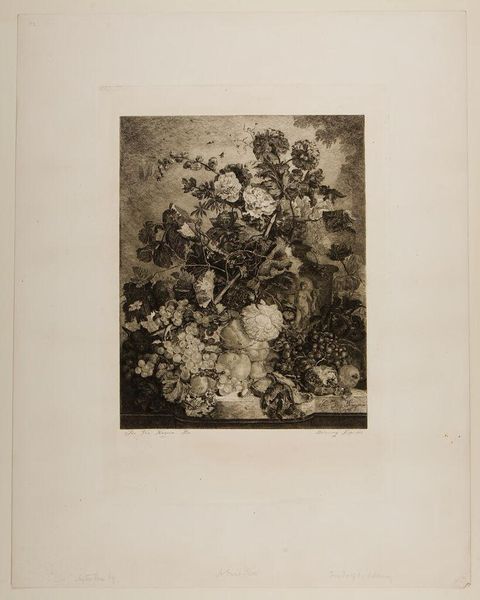

Editor: So this is Richard Earlom's "A Flower Piece, from The Houghton Gallery," created around 1778. It's a print, an etching made using drawing and paper, but it looks incredibly like charcoal. I'm really drawn to the almost photorealistic rendering, particularly considering the limitations of the printmaking process at the time. How do you see this piece fitting into its historical context? Curator: The photorealism you’re noting is fascinating because it intentionally obscures its means of production. Look at the etching – it’s mimicking the style and aesthetic of charcoal drawings, traditionally seen as preparatory sketches. But why elevate it to a finished print, reproducible for a wider audience? This raises questions about the artist's labour and how that is viewed by the market. Were Earlom’s print intended as a democratisation of art, or rather was the intent simply to sell the image using an inexpensive printing method? Editor: That's an interesting way to frame it! I was stuck on the composition itself, the aesthetic beauty. But thinking about the production process, were the patrons buying this print aware of or even concerned with the materials or process used in it’s manufacture? Curator: Absolutely. Consider the rising middle class in the 18th century. Prints like this allowed access to art previously reserved for the wealthy elite who commissioned original paintings. But it also changes the meaning of "originality" and ownership. It would be relevant to ask: What happens when art moves from a unique handmade object to a mass-produced commodity? The labour of the artist in producing multiples blurs the line between artistic creation and industry production. Editor: So, it's not just about *what* is depicted, but how that depiction was made accessible? I guess I was so focused on the flower arrangement itself, I didn’t stop to consider the labour involved. Curator: Precisely. It encourages a focus on not just the finished object but the social and economic structures that made its existence possible, making us aware of class, materiality, and the very consumption of art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.