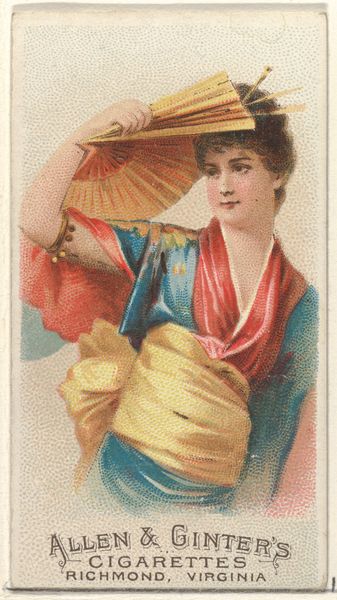

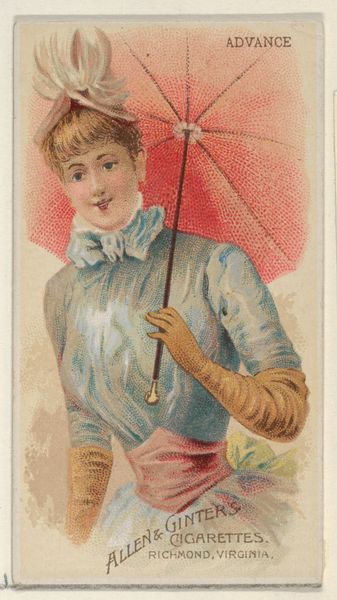

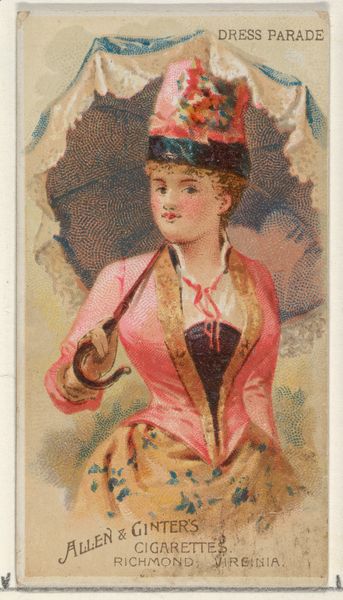

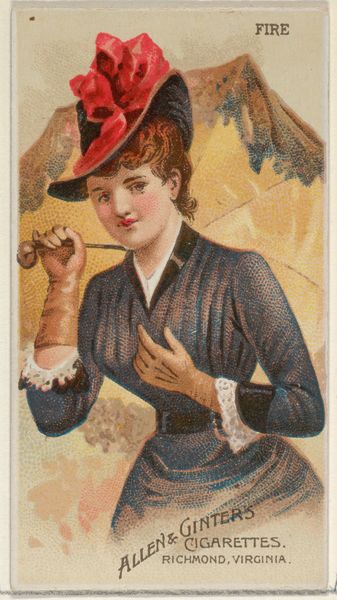

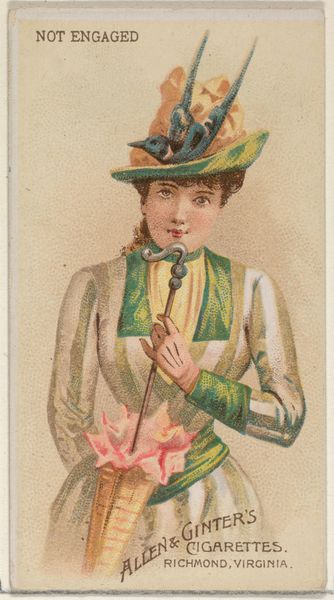

Best Company, from the Parasol Drills series (N18) for Allen & Ginter Cigarettes Brands 1888

0:00

0:00

#

portrait

# print

#

figuration

#

coloured pencil

#

watercolor

Dimensions: Sheet: 2 3/4 x 1 1/2 in. (7 x 3.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: What a fascinating little confection of an image. This is "Best Company, from the Parasol Drills series," a collectible card from 1888 by Allen & Ginter Cigarettes. It's currently housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: My immediate reaction is…intrigued by the materials! The almost pixelated rendering, likely from the print process, clashes interestingly with the idealized image of the woman. It creates an odd sort of tangible beauty. Curator: Absolutely, and let’s think about that “tangible beauty.” These cards, printed with colored pencil and other techniques, were inserted into cigarette packs. Imagine the contrast, then, between the ephemerality of tobacco consumption and the desire for these durable, collectable images. Editor: Right, a little piece of supposed art nestled amongst a pack of death sticks. What’s the social implication of that? How does it elevate or demean this young woman depicted? I also think about the factory workers who mass-produced them. Curator: It democratizes imagery, in a way. The company aimed to offer "premium" items, but it was still a capitalist venture driven by consumerism and, let's be honest, addiction. This particular series highlights parasols and fashionable women, reinforcing certain social values while advertising their brand. The brand’s success hinged on expanding tobacco consumption and normalizing gender roles, embedding that message within appealing images. Editor: Yes, it normalizes and sells lifestyles through visual enticement! What seems quaint today was shaping cultural perceptions and desires at the time, blurring lines between art, advertising, and social engineering. Curator: Consider the distribution—widely available due to its integration within cigarette packaging. It inserts imagery into everyday lives and turns collection into a habit, driving sales further. Allen & Ginter became known for the quality of their printed materials. Editor: Ultimately, a seemingly innocent, decorative piece, charged with material contradiction and institutional intention, deeply interwoven with production, commerce, and even ideas around feminine identity in the late 19th century. Curator: Indeed. The value lies not only in the image itself, but the journey it undertook from production line to pocket, reflecting the ambitions and anxieties of the era.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.