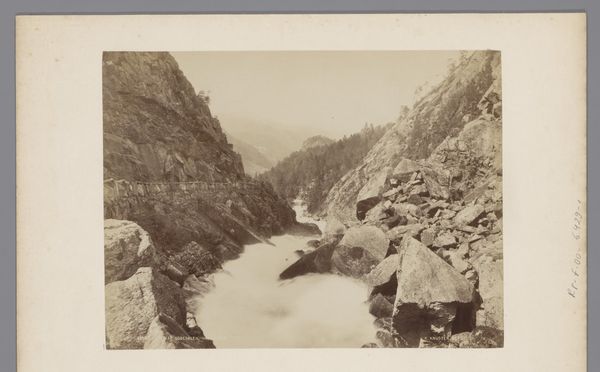

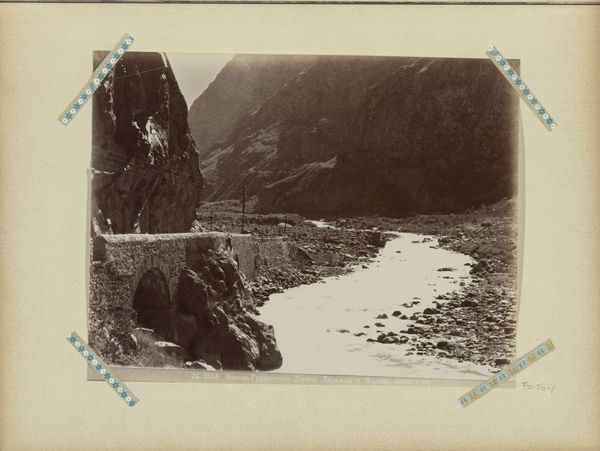

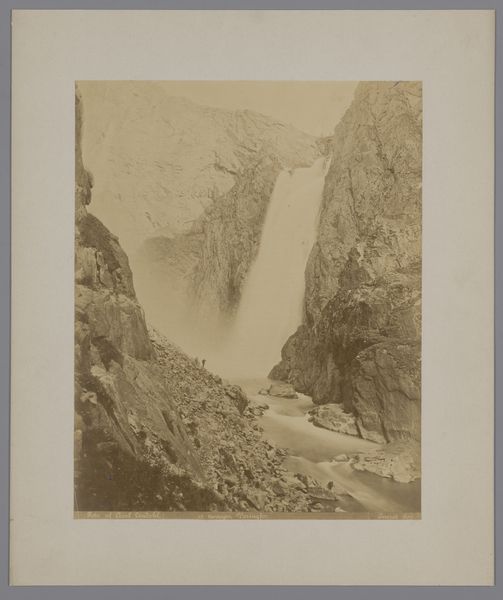

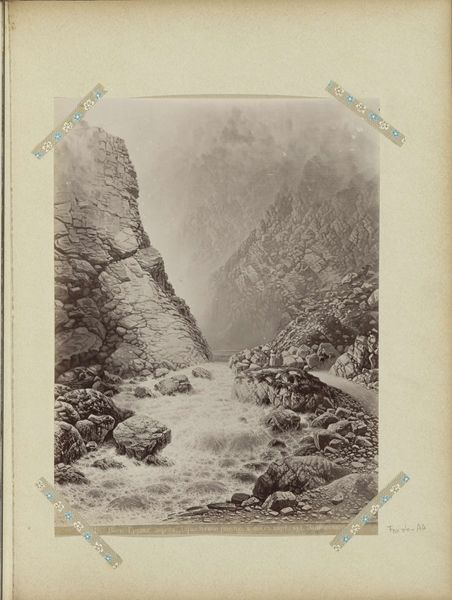

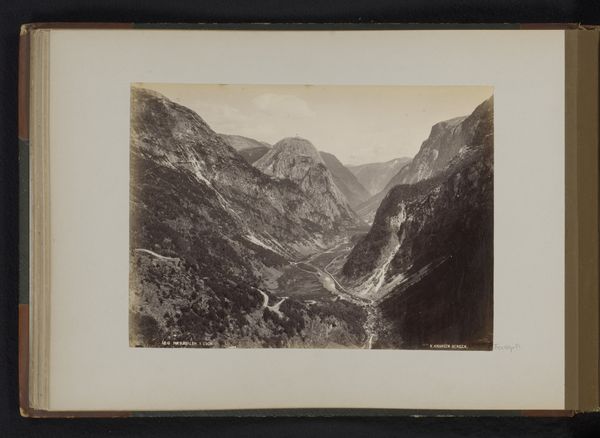

Dimensions: height 208 mm, width 265 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

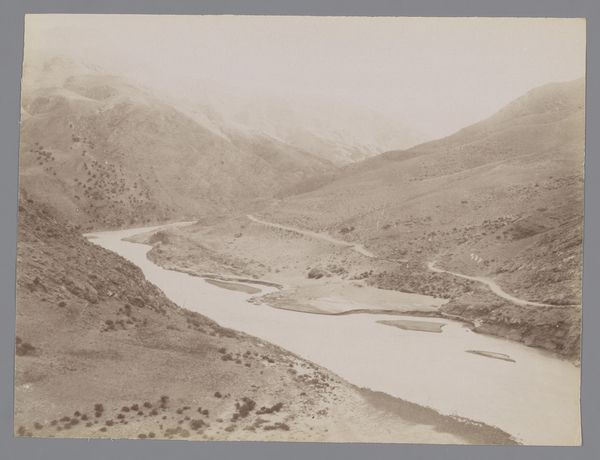

Curator: So, here we have Dimitri Ivanovitch Ermakov's "Mountain Landscape with River in Georgia," a photograph dating from around 1890 to 1900. It’s an albumen silver print. Editor: Wow, it's gorgeous. It looks almost like a painting! That blurred water gives the whole scene this dreamy, timeless feel. What an escape! Curator: It's more than just escapism though. Ermakov was documenting the landscape and cultures of the Caucasus during a time of significant Russian expansion. His photographs were often commissioned, so there is always an economic dimension at play too. It served the purpose of colonial surveillance and control. The sublime wilderness he captures would be integrated into the larger Russian imperial project. Editor: Interesting. It’s unsettling to consider such a beautiful image within a colonial framework. Looking at the detail in the rocks, it’s also impressive to consider the physical act of transporting photography equipment into remote areas. Ermakov's technical mastery combined with a vision truly transforms a landscape. It's so dramatic. Curator: Absolutely, but let's not forget this image, with all its romanticism, aestheticizes this rugged Georgian landscape during a tumultuous period of power dynamics and territorial ambitions. It presents a very particular and curated view. Editor: Of course, that's valid. However, that is why I resist the reading being so flattened by such sociopolitical factors only, and as an artist myself I understand that a desire to simply represent, to explore one's place and emotions is quite vital, too. To have something recorded with skill, in an interesting framing – it also just strikes me as valuable without any reading of colonial intention or expansionist political undertones. Curator: I get you – art *is* about connecting to universal themes of nature and beauty, outside the weight of colonial histories. This work captures an essential spirit, a timelessness perhaps… Still, I maintain that such romantic vistas served purposes intertwined with the socio-political structures of the time, to justify its colonial agendas. Editor: Indeed, let’s just say the water flows both ways in Ermakov’s art – pure, perhaps, but inevitably running through a landscape shaped by complicated history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.