print, photography

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

islamic-art

Dimensions: height 197 mm, width 252 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

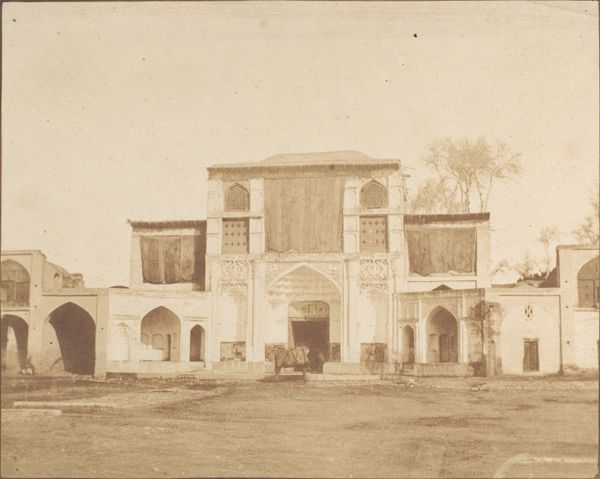

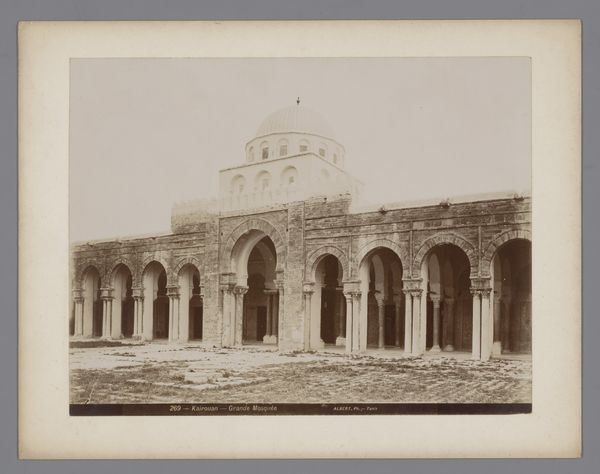

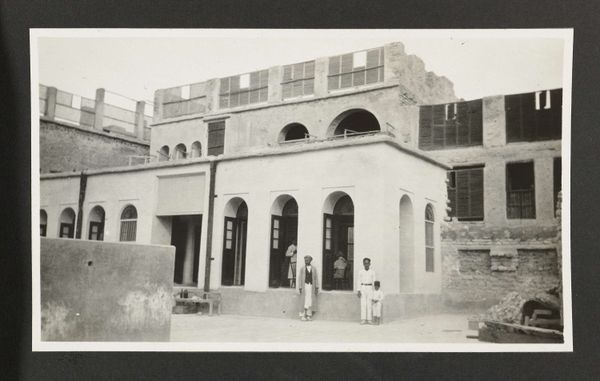

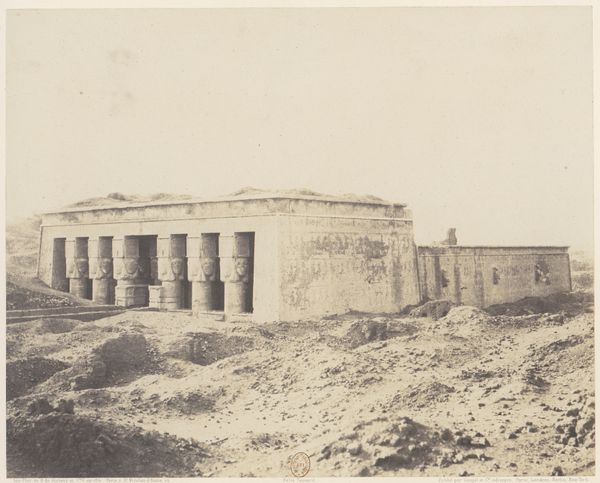

Curator: This albumen print, titled "Exterieur van het Bardopaleis in Tunis," dates from somewhere between 1880 and 1900. What strikes you first? Editor: Well, immediately I'm drawn to the stark materiality of the image itself. The texture of the aged print, the tonal range rendered by the albumen process… it evokes a tangible sense of history. It speaks volumes about photographic techniques of that era. Curator: Indeed. The very nature of photography then, with its complex chemistry and equipment, shaped the vision. How does it situate itself historically for you? The Bardo Palace has served diverse purposes and populations… Editor: Exactly. The Bardo Palace stands, documented in shades of sepia. Its imposing facade of brick, stone, or perhaps even concrete suggests the labor of many hands – their skill, their time, their lives intricately interwoven with the physical manifestation of power that the palace represents. Curator: I agree that we need to acknowledge the unseen labor within such representations of power. Let’s remember that in 1881, Tunisia became a French protectorate, adding layers of colonial complexity to the palace’s role. Editor: Precisely. It makes me question the conditions under which this photograph was created. Was it a commissioned work, and for whom? Who held the power in this exchange between photographer, patron, and place? What were the dominant materials of local art at the time? Curator: Those are vital questions. Think of the possible viewpoints – the photographer's gaze, the implied consumer's desires, the palace's symbolic weight within a changing political landscape. Even the framing positions this architecture. Editor: And the labor inherent in this artistic documentation must have demanded some consideration, especially in the way that a print makes even architectural grandeur somehow graspable, packaged, maybe even appropriated. The material itself carries that story, literally. Curator: Yes, it shifts the paradigm to understand all art within broader economic structures of making and consumption, which opens interesting historical and political conversations. Editor: It does. It reminds us that the beauty of art can, and must, provoke rigorous contextual questions about labor, social dynamics and historic realities. The image itself embodies and also exceeds the materials, becoming a question of ethics. Curator: It has changed the way I look at the photograph already. Thank you for your insights.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.