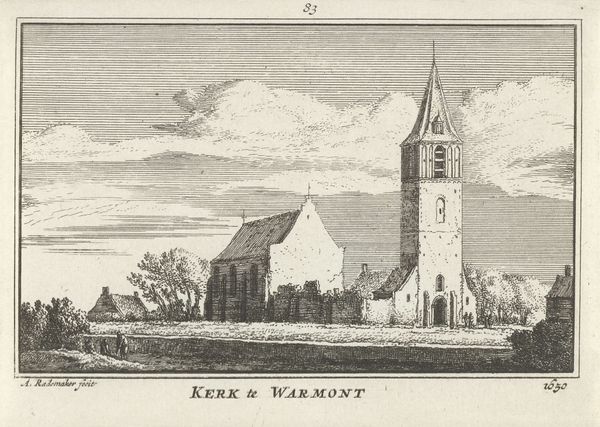

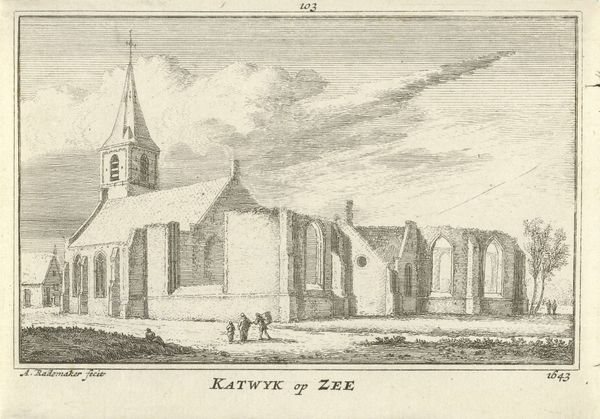

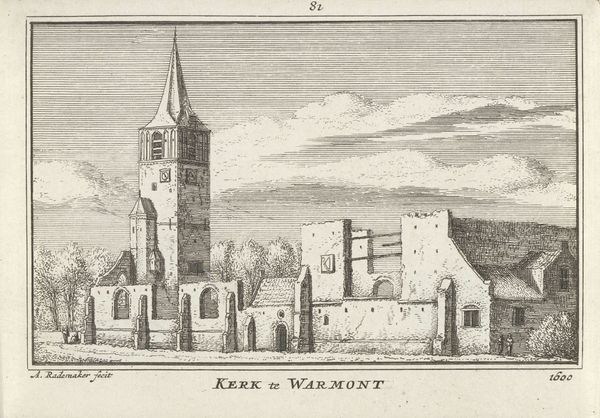

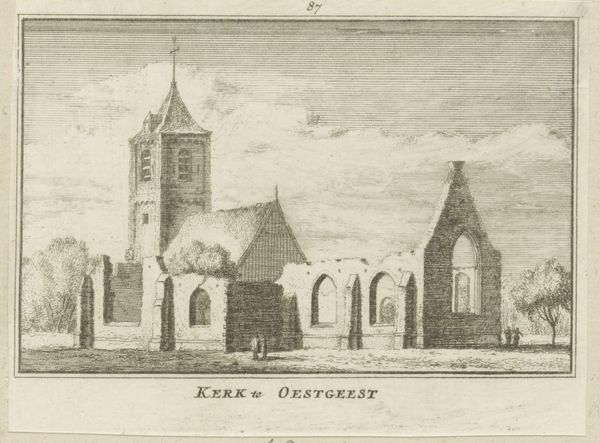

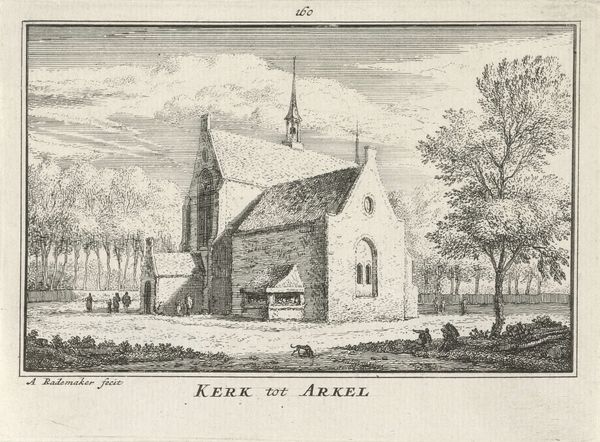

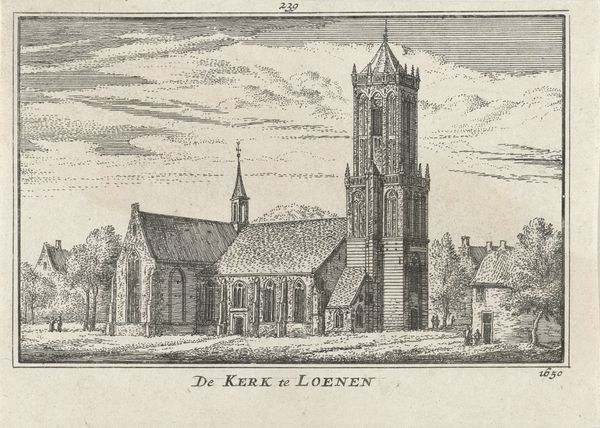

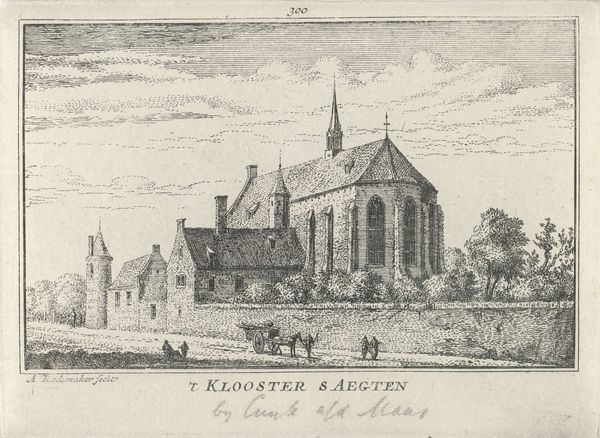

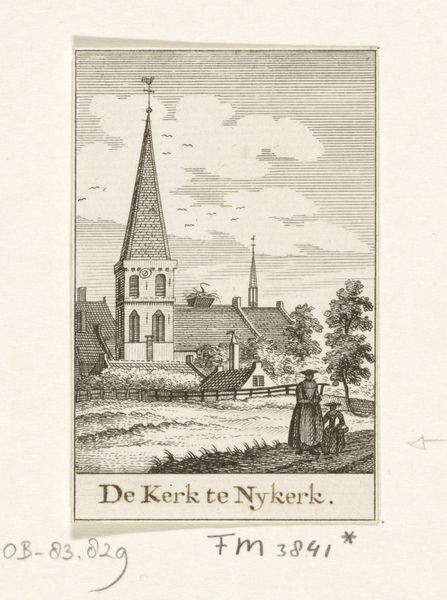

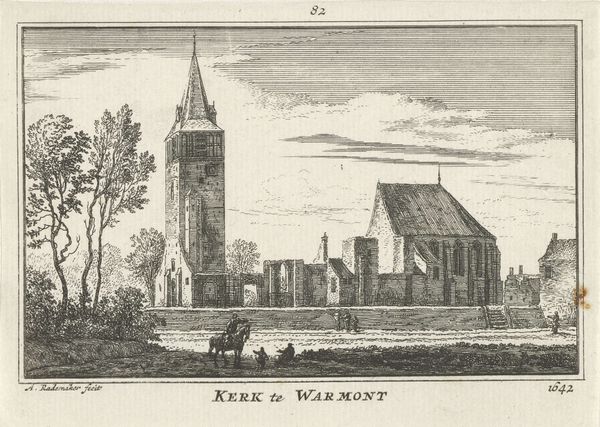

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 80 mm, width 115 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We're looking at "Gezicht op de Dorpskerk te Castricum," or "View of the Village Church at Castricum," a print made between 1727 and 1733 by Abraham Rademaker. It’s currently in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It feels serene. The delicate lines create such detail—you can almost hear the quiet rustling of leaves around the church. There’s a striking formality too, in the way Rademaker positions the church centrally. Curator: Rademaker was part of a movement interested in documenting Dutch life and landscapes. This print offers insight into the social significance of the church in a rural community of the period, capturing its imposing presence on the skyline of Castricum. Editor: Absolutely. And it highlights power structures, doesn't it? The church isn't just a building; it's a symbol of religious authority and community control. I’m also intrigued by the inclusion of everyday folk strolling on the road - that injects an element of the social dynamic between establishment and everyday life into the picture. Curator: Rademaker chose printmaking as the method here. Prints like this were easily reproduced and disseminated. Thus, in that time, it promoted a specific vision of the Dutch countryside, subtly shaping the nation's self-image. Editor: The deliberate composition also speaks volumes. Note how Rademaker uses linear perspective to lead our eye directly to the church. It’s a compositional decision but the hierarchy created implies that religion plays a prominent guiding force in the people’s lives in that location. Curator: Indeed. The formal style is typical of Baroque art and served the function of presenting the Netherlands as civilized, ordered, and inherently structured around influential entities like the Church. Editor: This piece goes beyond the picturesque, offering a glimpse into the complexities of societal organization and image cultivation in 18th century Netherlands. It challenges viewers to look beyond a pretty picture and acknowledge the encoded realities present in artworks of the time. Curator: Rademaker’s engraving leaves me pondering the way historical depictions shape our perception today, revealing that images aren't passive reflections of society but active contributors to how we understand ourselves. Editor: I’m leaving with a desire to disrupt linear narratives and spotlight overlooked dynamics, making space to confront art history as it collides with politics, belief and representation of marginalised people.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.