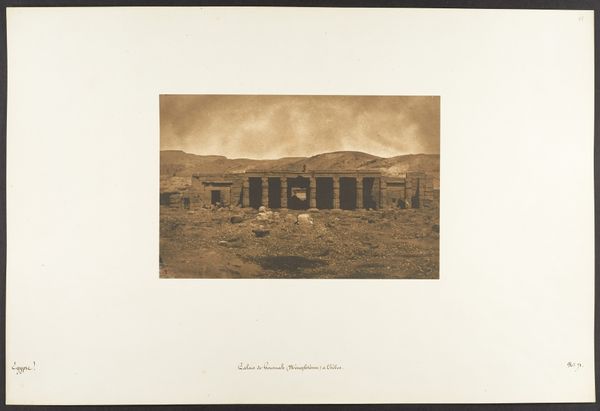

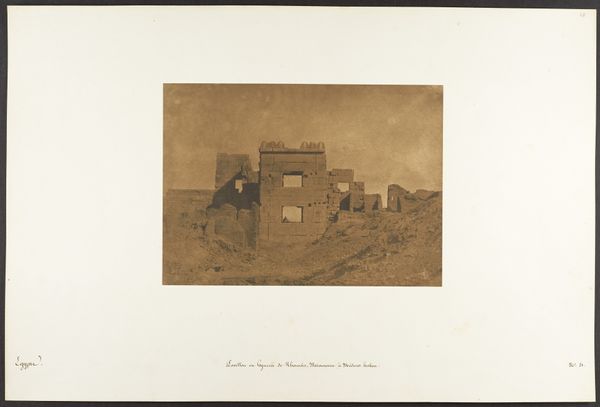

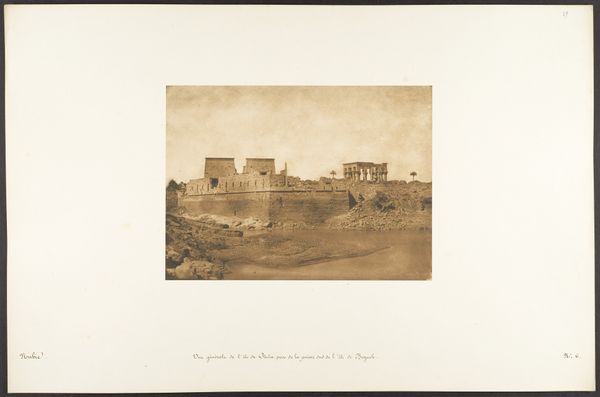

Vue générale des Ruines du Rhamesseum, à Thèbes (Tombeau d'Osymandian) 1849 - 1850

0:00

0:00

photography, site-specific, gelatin-silver-print, architecture

#

landscape

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

site-specific

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

architecture

Dimensions: Image: 5 11/16 × 8 11/16 in. (14.5 × 22 cm) Mount: 12 5/16 × 18 11/16 in. (31.2 × 47.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Before us we have Maxime Du Camp’s photograph, "Vue générale des Ruines du Rhamesseum, à Thèbes (Tombeau d'Osymandian)", taken sometime between 1849 and 1850. It's a gelatin-silver print. Editor: Striking how the desaturated tones create such a solemn atmosphere. The light seems to wash out the structure, blending its geometry into the landscape almost seamlessly. It certainly imparts a strong sense of antiquity, if not decay. Curator: Indeed. Du Camp, along with Gustave Flaubert, embarked on a journey to Egypt, and this photograph is a product of that trip. It is particularly noteworthy as it’s an early example of photography used for archaeological documentation and, therefore, its contribution to 19th-century Egyptomania. Editor: Tell me more about the composition itself. Notice how Du Camp positioned the ruins quite centrally. And the figure atop…a powerful decision to show its colossal scale but with a human presence. The architecture commands this plane! Curator: He’s employing the technology to record what was already being extensively depicted in painting and print media—the "Orient." I suggest Du Camp used photography to not only capture topographical and architectural information more “objectively” than traditional means allowed, but he’s participating in shaping popular perceptions and colonial attitudes towards Egyptian culture. Editor: Absolutely, although one cannot simply discount the formal beauty he managed to distill here, quite beyond the documentation itself. Consider the strong horizontal lines set against the column rows; how they play against the sloped plains and horizon, achieving visual balance. Curator: Yet, even this balance participates within colonial narratives. These "discoveries" bolster the West's sense of cultural and technological supremacy. We see, rather literally here, how the ancient world has fallen into ruin—presumably awaiting modern, European eyes to interpret it. Editor: So you’re indicating a visual hierarchy at play in both its immediate impression, but also Du Camp's role as a chronicler of history and a herald of a new cultural understanding that would have been impossible without photography? It offers the world to engage visually and contextually! Curator: Exactly. The photograph becomes less a neutral document and more an active participant in constructing an ideological landscape. It highlights how photography contributed significantly to the West’s construction of the East and itself. Editor: Interesting. I walked away with appreciation for Du Camp’s artful, even if seemingly passive, documentation. You give such weight to his impact in shaping—even propelling—socio-political dynamics. Food for thought.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.