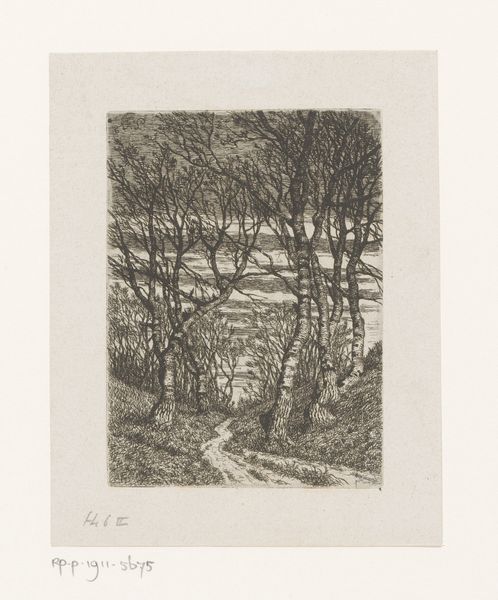

![A Lonely Farm [Hawkridge] by Robert Polhill Bevan](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzL2ZhZDc1MzNmLWVlN2UtNDU0Ny05MWYxLTM1MjU3NmE5ZGJiMS9mYWQ3NTMzZi1lZTdlLTQ1NDctOTFmMS0zNTI1NzZhOWRiYjFfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

Dimensions: image: 34.8 × 40.5 cm (13 11/16 × 15 15/16 in.) sheet: 45.9 × 55.9 cm (18 1/16 × 22 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

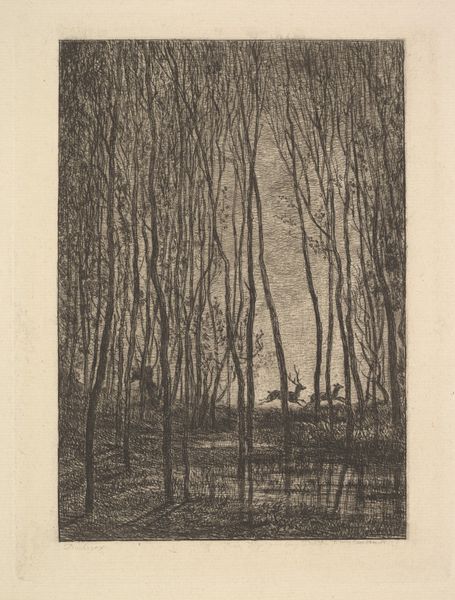

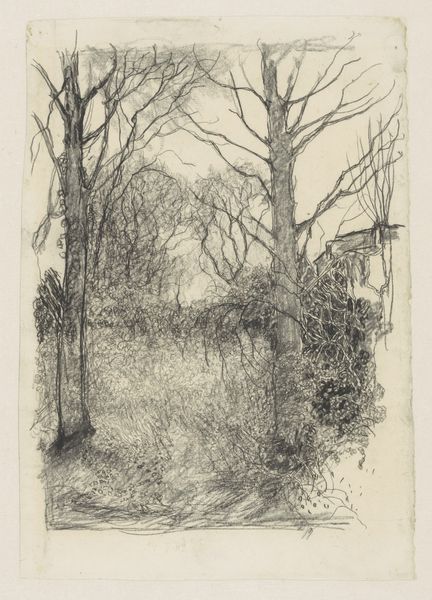

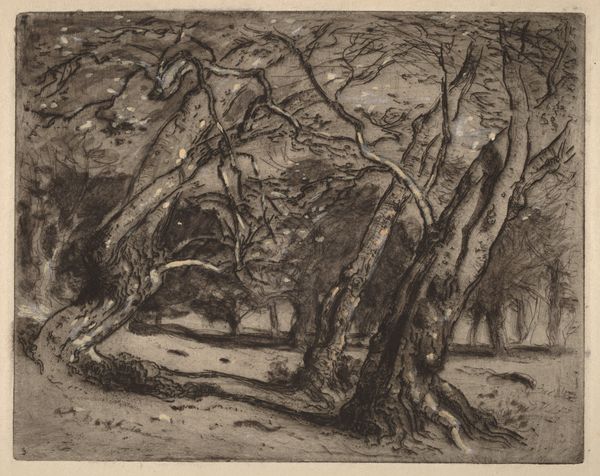

Curator: This piece is entitled "A Lonely Farm [Hawkridge]," crafted around 1900 by Robert Polhill Bevan. It appears to be a graphite drawing, or perhaps a print made from one. Editor: My first thought is of solitude. The stark, almost claustrophobic monochrome palette combined with the lone light in the house evoke a sense of stark isolation. Curator: Bevan, although associated with Impressionism, had a distinctive vision. Let's consider the social context: the late 19th-century agricultural shifts, rural exodus. Doesn't this image resonate with a narrative of societal displacement? What voices might have been excluded at the time that Bevan is giving space to? Editor: Indeed. And the materiality of the print or drawing further reinforces this. The density of the graphite suggests a weight, a pressure almost reflecting the manual labor involved in farming. It draws attention to the physical act of production, doesn't it? Bevan, who had connections with Gauguin, emphasizes surface in this work through his repetitive mark-making. Curator: I see how the repetitive mark-making embodies labor. There's an undeniable tension. The house, illuminated, provides a focal point amidst the encroaching darkness of the woods, like a symbol of both refuge and vulnerability. Are we, as viewers, implicated in the forces isolating that little light in the building, contributing to this narrative in a modern market-driven environment? Editor: Precisely! The printmaking process allows for replication and distribution, potentially democratizing the image but also turning this isolation into a commodity for urban consumption. There is so much texture from the layering of material and ink that really creates a stark contrast between dark and light. Curator: And there is a ghostly essence with the absence of people from the landscape, the emptiness. It prompts reflection on the social inequalities inherent in artistic representation during that time, and it remains hauntingly relevant today. Editor: Ultimately, it makes us think about the cost, material and human, involved in creating an idealized view of rural life that would hang on the walls of a middle-class drawing room. Curator: Yes, it's about uncovering the intricate, interconnected layers of production, representation, and reception. Editor: Absolutely.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.