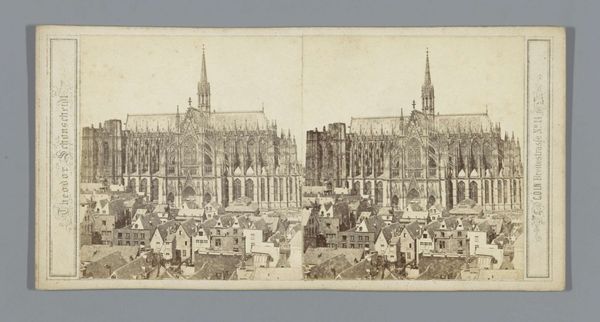

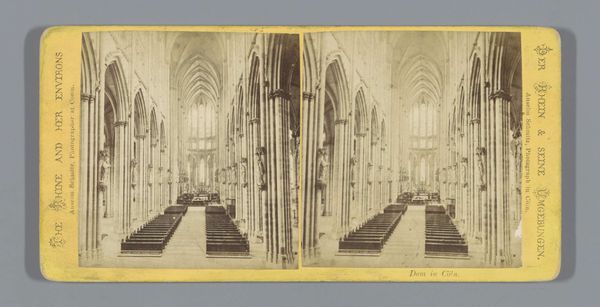

Dimensions: height 85 mm, width 170 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a fascinating gelatin silver print dating from about 1865 to 1875, attributed to Theodor Creifelds. The subject is a cityscape—specifically, the Cologne Cathedral. Editor: It strikes me immediately as quite imposing, despite its somewhat faded appearance. The sheer scale of the cathedral is emphasized by the way the image is constructed. Curator: Indeed. Creifelds captured the Dom at a key moment, during its protracted construction. Work on the cathedral had begun in 1248, stalled in the 15th century, and was only restarted in the 19th, fueled by a surge of nationalistic sentiment and a desire to complete this symbol of German identity. Editor: The cathedral looms large—a kind of aspiration, certainly, a symbol of something almost beyond human reach. Churches, especially Gothic ones, so often have this air about them, but with the added historical weight you mention, this particular structure just dominates. I'm struck by the cranes, the scaffolding still clinging to the towers. There’s something potent about the incompleteness of the divine. Curator: The photographic medium itself adds layers to that symbolism. The rise of photography coincided with this period of renewed national fervor, and images like this played a crucial role in shaping public perception, becoming potent symbols of progress and national unity. They sold very well. Editor: Do you think the photograph therefore emphasizes how national fervor was made concrete, made real, brick by brick? Was this construction of Cologne Cathedral also constructing something else? Curator: Absolutely. The completion of the cathedral became a symbol of a unified Germany, something eagerly consumed as photographs like these spread the image far and wide. In that light, this particular gelatin-silver print reminds me how much imagery served national ambitions. Editor: It shows that a potent symbol does not need to be perfect or immaculately preserved to communicate meaning; that incomplete nature may even make it more powerful, implying aspiration beyond our present selves. Well, it makes you think. Curator: It certainly does, reflecting on the public role of art and its connection to historical and socio-political forces gives the image a compelling richness.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.