print, photography, site-specific, gelatin-silver-print, architecture

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

site-specific

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

cityscape

#

italian-renaissance

#

architecture

#

realism

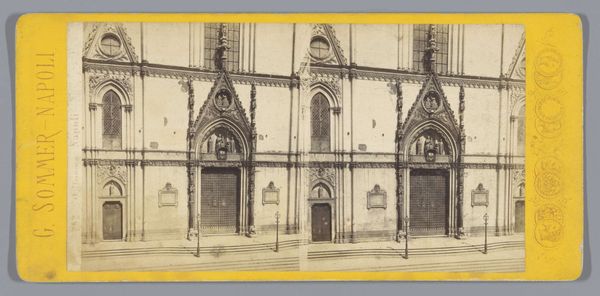

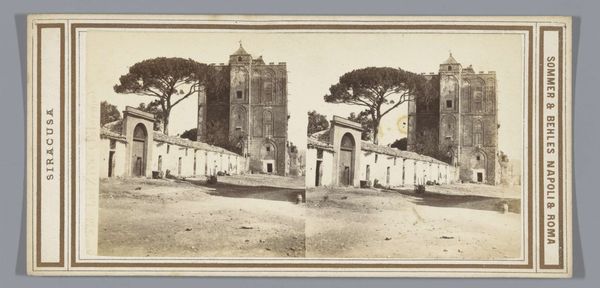

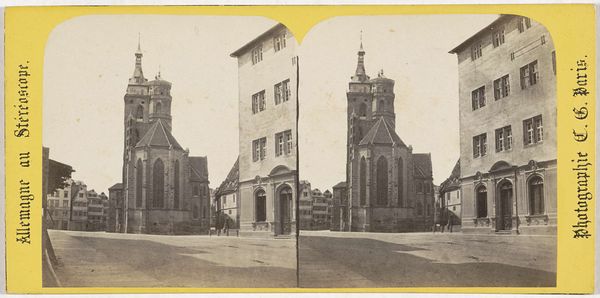

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 178 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at Giorgio Sommer’s gelatin silver print, titled "View of San Rufino in Assisi," created somewhere between 1860 and 1880, I am immediately struck by its imposing presence and intricate detailing of this religious space. Editor: It's heavy, isn’t it? I mean literally, looking at the image, the density of the stone and the obvious labor required to construct the basilica radiates outward. There's a definite materiality dominating everything else. Curator: Indeed. Think about Assisi as a major pilgrimage site, particularly linked to St. Francis, whose association profoundly shaped notions of poverty, humility, and connection to the natural world. The grand basilica shown here represents both an assertion and subversion of those values. Editor: I agree; it's a statement, built and maintained using specific methods. You know, the physical labor required and the sourcing of those materials. It raises questions about power and who benefits from the production of these large scale projects. Were they using local quarries? Who were the stone masons? What were their working conditions? Curator: Precisely! This basilica wasn’t erected in a vacuum. The labor involved likely included various classes and levels of expertise. Analyzing that power structure allows us to understand the intersections of artistic production, economic systems, and the deeply embedded gendered divisions of labor at the time. The act of photography itself also serves to democratize spaces traditionally held only for particular classes or purposes, opening new avenues for examining art, architecture and social relations. Editor: Absolutely, thinking about the wet-collodion process alone—the preparation, the development. It’s crucial to understanding not only the image-making but also how widely this kind of photography could actually circulate at the time. This specific image almost feels mass-produced. The stereocard format allowed mass reproductions—art as commodity! Curator: Which highlights a complex interplay between spirituality, class, and representation in the context of nineteenth-century Europe. These seemingly simple landscape views held deeply gendered perspectives tied to colonial ideals about place and ownership. Editor: Exactly! From my perspective, digging into the means of production challenges these inherent power structures by pointing back to labor, context, and materials themselves. Curator: Thinking about all this has only deepened my understanding of the intricate historical and social meanings intertwined within this powerful photograph. Editor: And for me, focusing on those construction elements and material processes makes it possible to interpret the photograph and challenge traditional, often exclusionary, definitions of art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.