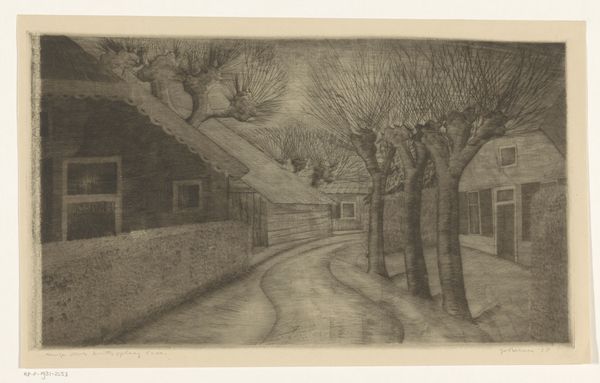

Dimensions: height 198 mm, width 262 mm, height 292 mm, width 360 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

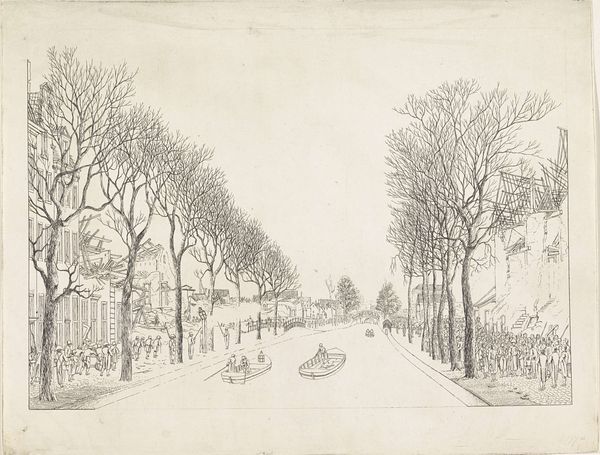

Curator: Here we have Unichi Hiratsuka’s "Akasaka Palace," a woodblock print dating to 1945, currently held in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. Editor: There's a certain tranquility despite the date, wouldn't you agree? The light palette and straightforward composition give it a surprisingly placid feel. The muted blue contrasts delicately against the cream-colored paper, constructing a calming symmetrical urban landscape. Curator: Well, 1945 marks the end of World War II, a profoundly significant moment in Japanese history. The almost melancholic simplicity you perceive might stem from Hiratsuka's effort to depict a landscape recovering from such widespread trauma. The Akasaka Palace, in this light, could symbolize resilience and the endurance of Japanese culture. Editor: Interesting take! However, considering formal aspects, observe how Hiratsuka uses the repeating verticals of bare trees and the orderly arrangement of forms, all echoing each other. Note the composition guiding the viewer’s eye straight toward the palace. What about the almost uniform texture throughout the surface of the paper, lending itself well for the overall visual experience? Curator: That's an astute observation. Yet, if we zoom out a little more, consider how this image was created in the same period of profound social change within Japan— a time when the very foundations of the imperial system were being questioned and challenged. The serene palace façade masks potentially turbulent shifts in national identity. Its physical structure, replicated uniformly, becomes a question itself, rather than a fact. Editor: Yes, of course. I am with you—semiotics can serve us. In that perspective, this image serves not just as a record of space but perhaps reflects on architecture becoming an emblem, which stands between the city and an individual. However, looking from material’s point of view: the printmaking and carving lines become an expression method as such and bring visual satisfaction, nothing less! Curator: I can’t help but think about how these art historical contexts reframe the image, complicating its seemingly uncomplicated nature. Considering social narratives, what might viewers feel during those changing times when seeing such governmental buildings in replicated formats? What kind of commentary the artist implied when repeating these rigid lines? Editor: Indeed, bringing context is never a bad practice. Curator: Agreed; that balance allows for a richer engagement with art!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.