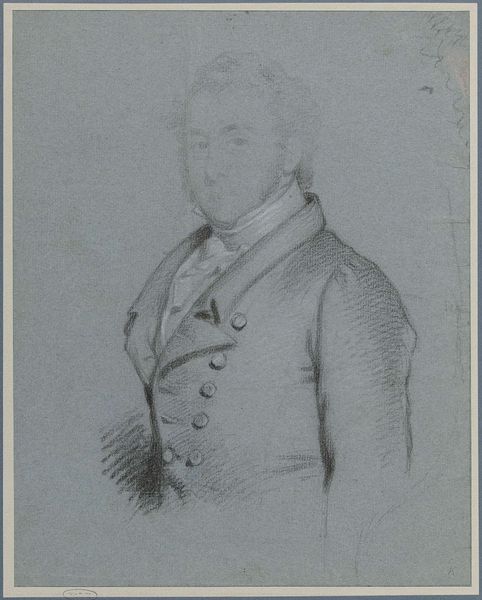

drawing, graphite, charcoal

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

charcoal drawing

#

pencil drawing

#

romanticism

#

graphite

#

charcoal

Dimensions: height 195 mm, width 162 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

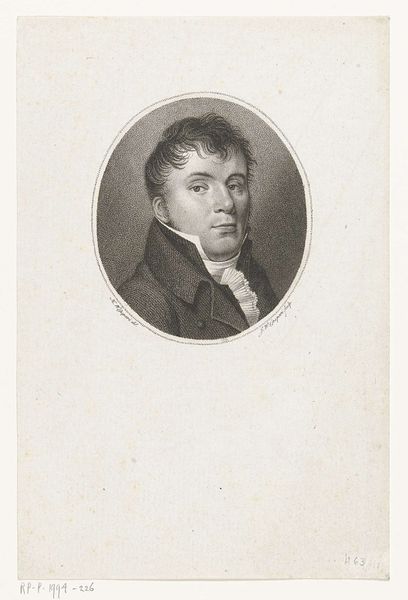

Curator: Here we have a work entitled "Portret van Willem Grebner," estimated to have been created sometime between 1800 and 1830. The medium appears to be graphite and charcoal on paper. Editor: It has a kind of austere charm, doesn't it? There's a subdued, almost ghostly quality in the subject's face, emphasized by the monochromatic tones. Curator: Indeed. The oval format reinforces the tradition of portraiture, channeling a certain timelessness. The artist uses subtle gradations of tone to define form. Note how the light falls to create a sense of volume. Editor: Yes, but look closely at the application of materials; you can see individual strokes, the hand of the artist quite literally *in* the making of this portrait. I imagine the artist painstakingly building up the shadows with charcoal dust, perhaps even using a cloth or soft tool to soften the harsher edges, thus allowing light to describe contours smoothly. Curator: Precisely. It’s also important to acknowledge how the Romantic era informs its visual rhetoric; you have elements of naturalism married to emotional expression. Grebner's composed gaze projects an intensity, reflective perhaps of the shifting political landscapes of that time. Editor: Or perhaps we’re seeing the hand of commerce here? Commissioned portraits were a source of revenue, so the quick application of materials speaks to practical economy: time saved could generate profits. Graphite and charcoal were much less costly than oil paints. What sort of economic pressures influenced Grebner to be portrayed in charcoal rather than more lavish, pricier media? Curator: An interesting avenue for thought. And consider how this piece transcends mere representational depiction, acting instead as a symbol of social and personal identity formation at the threshold of modernity. It raises fundamental issues of portraiture as visual form. Editor: Maybe so. For me though, the true revelation resides within that visible act: smudging, stroking, blending until it’s done… It suggests both intention and execution within socio-economic contexts! I'm captivated by how our subject becomes *visible* only after such artful toil. Curator: A compelling articulation indeed. I find I look more at the structure and composition as defining visual signifiers. Editor: Well said.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.