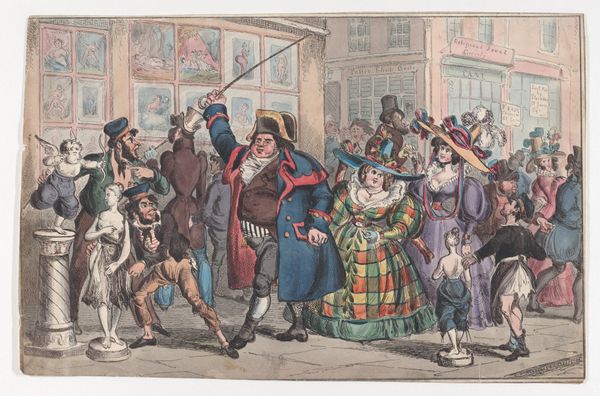

print, watercolor

# print

#

caricature

#

watercolor

#

folk-art

#

romanticism

#

watercolour illustration

#

genre-painting

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

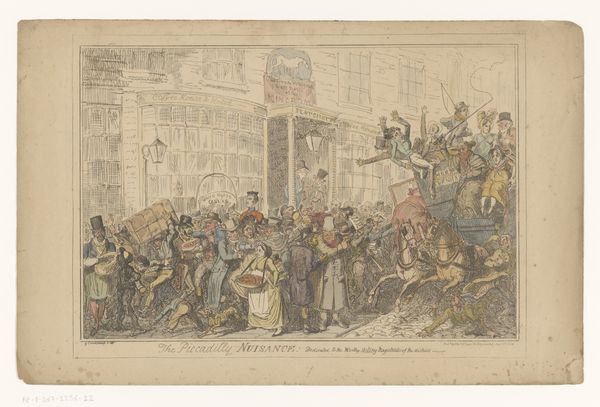

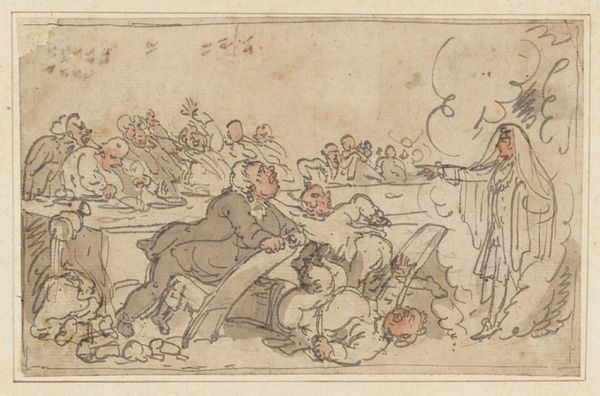

Curator: Let’s delve into Thomas Rowlandson's “The Inn Yard on Fire,” a watercolor and print from 1791. Chaos, isn’t it? Editor: Utterly! My immediate reaction is a kind of dark humor—a frenetic scene depicted with a palpable sense of panic and social disruption. I mean, look at the bodies piled in wheelbarrows—are those animals being carried to safety along with people? Curator: Exactly. Rowlandson, renowned for his caricatures, really leans into the means of production of such prints at this time and who was consuming them—consider how the labor of producing these prints for a rapidly expanding middle class reflects on the subject matter itself: a society seemingly on the verge of combustion. Editor: It's a fantastic depiction of societal anxiety during the late 18th century, too. Think about the French Revolution brewing across the Channel; the strict social hierarchies being challenged. This fire, depicted as it is, is metaphorical for a system about to collapse—note how figures from different social strata are thrown together haphazardly. And the romantic undertones underscore how revolution often involves a return to nature. Curator: The use of watercolor layered over the etching allowed for a mass produced image that appears unique, and created the overall impression of a quick sketch, perfectly captures that fleeting, feverish moment. This fire is obviously devastating but, to Rowlandson, it also presents a chance to examine society’s structural weaknesses. Notice how he gives a tremendous sense of movement to the eye of the viewer throughout the pictorial field by making extensive use of orthogonals Editor: I'm particularly struck by how he spotlights the grotesque aspects of people amidst the drama. Are these people being caricatured, or is this how their basic human qualities are laid bare by disaster? Consider the power dynamics on display as some profit from it, too—we have men climbing up a ladder presumably with the intention to burglarize the premises on the upper floor, so in its entirety it speaks to themes of human exploitation and survival in turbulent times. Curator: Precisely. Rowlandson used readily available materials to poke fun at what was bubbling under the surface, laying bare how flimsy were the boundaries between order and disorder at this time. It asks us to question not just what we see, but how it was made, who it was for, and what work it’s doing. Editor: And it succeeds. It's more than just a historical record; it serves as a cautionary tale about society's fault lines that we see continue in many ways today— class disparity, exploitation of labor, lack of care and empathy. Art becomes an uncomfortable mirror reflecting us, as always.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.