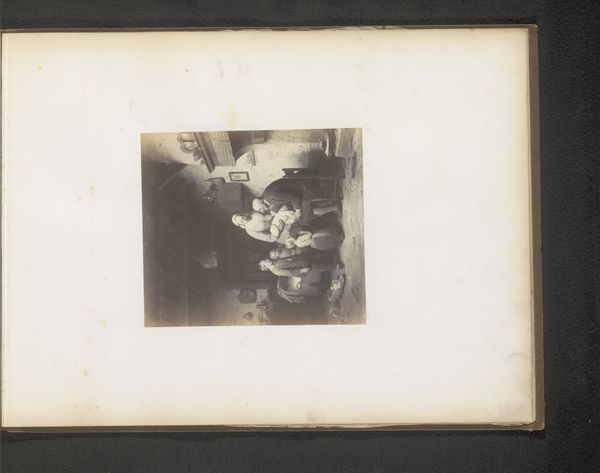

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

street-photography

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 119 mm, width 153 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a photographic reproduction, a gelatin-silver print, of Charles de Groux's painting "Le moulin à café," which translates to "The Coffee Grinder." It's part of the Rijksmuseum collection and dates back to before 1863. What springs to mind for you upon seeing this piece? Editor: An almost oppressive silence. It's as though the very air is thick with unspoken stories, shadowed faces huddled in muted conversation. The narrow alley and subdued tones really give it a sense of melancholic mystery. Curator: Absolutely, the scene oozes the quiet intensity typical of genre paintings of the era, and you see, of Realism, really. The everyday life of ordinary people—it attempts to depict reality, however grim. Note the figures gathered around the apparent coffee grinder – possibly a social hub, or perhaps just a necessity. Editor: I immediately zero in on the object itself: the coffee grinder. Thinking about its industrial materiality, its presence signifies not only daily sustenance but the burgeoning accessibility of global commodities. I wonder who made it and the labor conditions involved in its creation? It's far more than an image; it is deeply rooted in specific manufacturing. Curator: A stark contrast, yes, to how the artistic eye would observe it: De Groux captured, and the photographer replicated, the emotional and social realities surrounding this object. There’s a feeling of community, poverty, or even the simple act of sharing stories alongside brewing coffee. It acts as a quiet window into another world. It invites pondering about their lives. Editor: And think of the technical labor, though, involved in this print: the alchemy of gelatin-silver, a relatively new medium back then, attempting to replicate a painting—a new art literally consuming the old! What layers of making can reveal... And who got to see these reproductions; to whom did it give access that they previously didn’t have? Curator: And consider its social impact. Perhaps it aimed to invoke empathy for the working class. The play of light and shadow—a characteristic aspect of realism at the time, and here also so evident in the final print. What stories this reproduction tried to replicate. What a moment to meditate upon; a painting of a scene available thanks to another mode of production. Editor: Ultimately, the power of the image comes through – and that object, transformed across media, keeps fueling our historical inquiry. Thank you for leading us down such a revealing path!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.