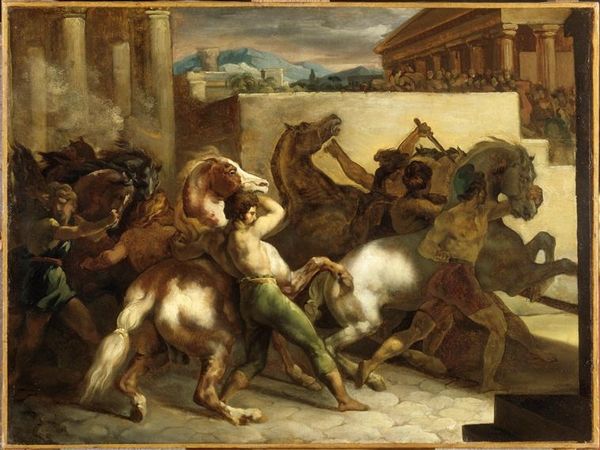

Study for the Race of the Barbarian Horses 1817

0:00

0:00

theodoregericault

Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille, Lille, France

drawing, painting, charcoal

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

painting

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

horse

#

charcoal

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 60 x 45.1 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Editor: Géricault’s "Study for the Race of the Barbarian Horses," created around 1817, bursts with dynamic energy. It's a charcoal and oil study, and I’m struck by how turbulent and almost violent the whole composition feels. What do you see in this piece beyond the obvious chaos? Curator: It’s interesting you use the word “violent.” Consider the context: post-Napoleonic France, a society grappling with upheaval, class divisions and deeply embedded colonial power dynamics. The “Barbarian Horses” themselves become symbolic, don’t you think? Representing unrestrained power, maybe even the repressed energies of a nation trying to redefine itself after years of conflict. What's your interpretation of the 'race' itself? Is it simply a sporting event? Editor: I hadn’t thought about it that way. I guess I saw it as just a race, a spectacle. But thinking about it through the lens of societal upheaval, the race could be a metaphor for the struggle for dominance. Curator: Precisely! And look at how Géricault renders the figures—their struggle, their barely controlled power over the animals. This speaks to the fraught relationship between humanity and nature, a relationship tinged with exploitation and control, mirroring France's colonial endeavors. How might ideas about the exotic "other" play into the composition? Editor: So, it's not just about the aesthetic appeal of the race but also about the deeper societal anxieties and power structures at play. That really shifts my perspective on it. Curator: Exactly. Seeing art as more than just aesthetics, but also as a cultural and political artifact, opens up so many possibilities. It forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about ourselves and the world we've inherited. Editor: This makes me look at historical paintings completely differently now. It’s not just capturing a moment, it's actively participating in a dialogue about power and identity. Curator: And isn't that what makes art so endlessly fascinating? It’s always in conversation with its context and with us.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.