print, fresco, woodcut

#

medieval

#

narrative-art

# print

#

figuration

#

fresco

#

woodcut

#

history-painting

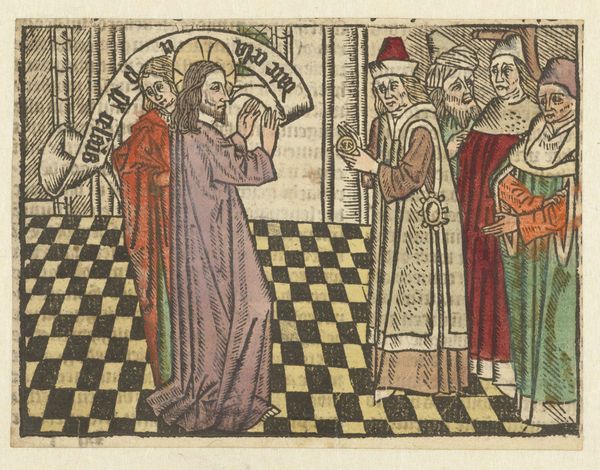

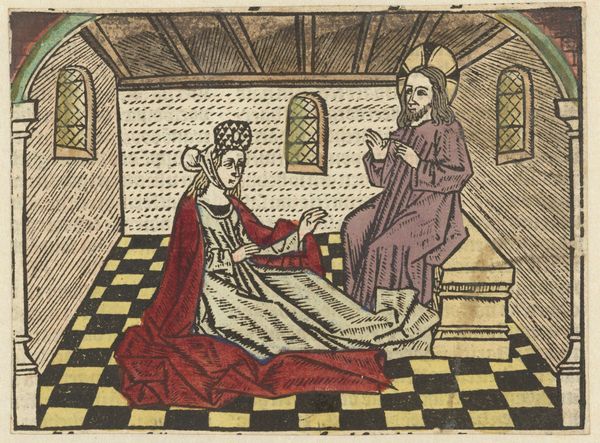

Dimensions: height 94 mm, width 127 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This woodcut, "Christus en de overspelige vrouw" or "Christ and the Adulterous Woman" comes to us from the Master of Antwerp, active in the late 15th century. Editor: Woah. The moment I look at it, there’s a kind of stilted stillness to it. Like actors waiting for the next cue, except the stage is a rather fetching black and yellow checkerboard. I wonder if it feels so still because it looks like it’s a woodcut. Curator: That’s insightful. Its being a woodcut influences its impact. Notice the limited tonal range. How does the texture emphasize the narrative’s moral dimensions for its contemporary audience? Editor: Hmmm... “Moral dimension.” You know, the lines feel incredibly tense. Like the morality is trapped, hardened like wood or dried plaster. See how each line carves out the figures, giving a rather graphic feeling? What do you make of those severe, unwavering gazes from the people who are confronting the woman? Curator: Those stares reinforce societal judgment, yes. Medieval prints played an essential role in conveying biblical narratives to a largely illiterate population. The architectural details and figure types communicate moral lessons about justice, sin, and redemption. Christ’s bending posture indicates a counterexample to the stances and attitudes shown by everyone else in the artwork. Editor: It’s that bent-over posture I’m focusing on too. He's writing, it appears. Is he documenting the moment or refuting it? It gives us a key moment within the grand, dramatic tableau. And also I feel it personalizes his experience. Like he feels sorrow or pity for this moment as opposed to righteous anger. Curator: Exactly! This particular scene had wide distribution via prints and frescoes. Its circulation and republication is as relevant as any particular audience receiving it. Editor: Which says a lot. Because even now, several centuries later, there's still that haunting feel that this happened to one woman... or might have. Curator: Yes, that’s a testament to its enduring relevance in discussions about compassion and law. Editor: Indeed. Every era reinterprets its own lessons. The beauty here, though, lies in its visual power to ignite it again in someone experiencing the work, for the very first time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.