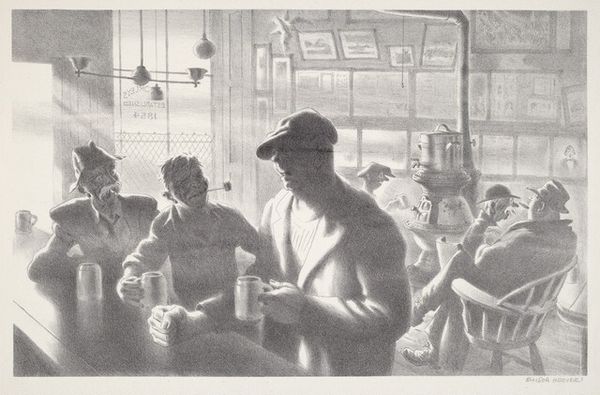

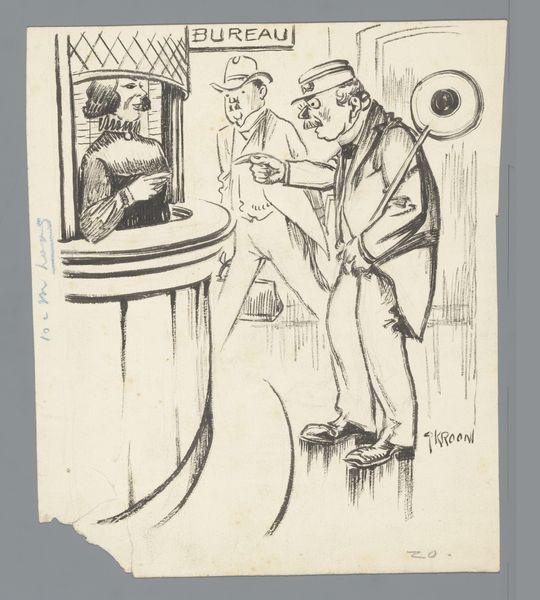

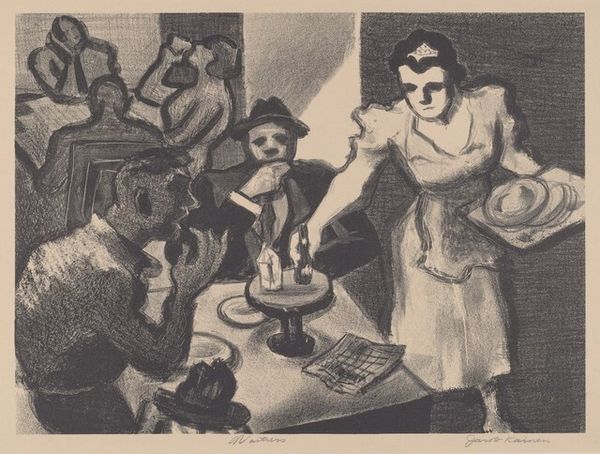

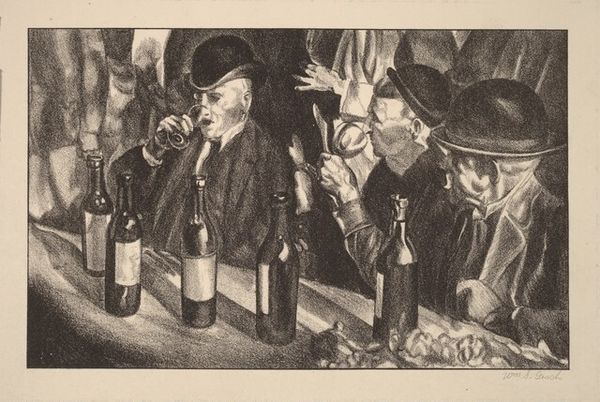

drawing, print, graphite, charcoal

#

portrait

#

art-deco

#

drawing

#

self-portrait

# print

#

surrealism

#

graphite

#

portrait drawing

#

charcoal

#

realism

Dimensions: image: 278 x 351 mm sheet: 443 x 573 mm

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Kenneth Hartwell created this drawing, "Untitled (Self Portrait at the Barber Shop)" in 1932. It looks to be graphite and charcoal on paper. What are your initial thoughts on the piece? Editor: It feels like a slice of life, though an intensely shadowed and weighty one. The sheer density of objects and people crammed into the composition creates a slightly claustrophobic atmosphere. Curator: Absolutely. This work prompts reflection on masculinity, both its performance and the spaces where it's cultivated. Hartwell situates himself in this very codified social space, inviting a discourse around identity. Editor: Let's consider the context of barbershops during the early 20th century. They were crucial communal hubs, locations where men could network and share thoughts, influencing local politics and social bonds. This drawing reveals labor and social connection. Look at the detail in those grooming tools and bottles! Curator: I'm fascinated by the interplay between visibility and erasure here. Consider, for instance, the repetition of faces—are they echoes of Hartwell's anxieties, fragmented aspects of his persona struggling for representation in a rapidly changing society? The barber seemingly looming directly over Hartwell feels significant. Editor: Note also the materials: the stark black and white rendering adds to the feeling of being suspended in time, further emphasizing a link to both the production and performance of traditional values. It highlights how men constructed themselves and how this identity creation may be linked to consumer practices. Curator: Hartwell also places himself as the focal point. It is more than just about getting a haircut; the intimate portrayal and the reflective setting within a very traditionally masculine sphere may ask a viewer to reflect on what those spaces mean in relation to the politics of gender, especially when considered in the 1930s. Editor: Yes, the interplay between Hartwell's own self-awareness as an artist representing himself alongside the practical tools of barbering—scissors, brushes, and soaps—demonstrates the connection between art making and the working class. Curator: Viewing this artwork allows us to reflect on individual identities and how societal norms intersect. Editor: Indeed. Hartwell offers a moment captured, allowing a discourse about creation in labor, performance, and representation to unfold.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.