photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

culture event photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 135 mm, width 86 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

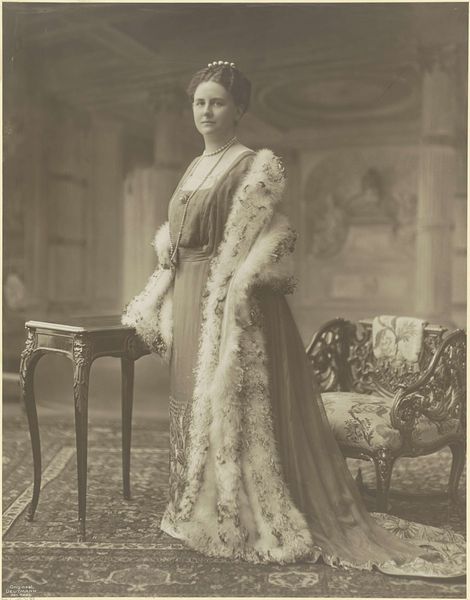

Editor: Here we have Herman Deutmann’s “Portret van Juliana, koningin der Nederlanden,” a gelatin silver print from somewhere between 1921 and 1929. The young princess looks so serious, almost weighed down by her opulent gown. What can you tell me about its cultural significance? Curator: It’s fascinating how photography cemented royal imagery, isn’t it? Prior to widespread photography, royal image management depended largely on painted portraits. This gelatin-silver print captures a specific moment, carefully staged for public consumption. Consider the date, around the 1920s – a time of social and political upheaval. How do you think this portrait contributed to constructing an image of stability and tradition? Editor: It feels like a calculated attempt to project an image of enduring power amidst societal change. All the regal attire certainly adds to the effect. But I wonder, what kind of public was this photograph meant to reach? Curator: It was likely aimed at both domestic and international audiences. Domestically, royal portraits served to reinforce national identity and unity. Internationally, they presented a modern yet traditional face of the Netherlands. The use of photography itself, a relatively new medium at the time, indicates an understanding of how to engage a wider public than ever before. Have you noticed anything about the chair she’s seated in, the textiles, or other background elements? Editor: Now that you mention it, the elaborate chair and decorative items behind her also seem carefully chosen to convey wealth, status and connection to Dutch heritage, especially as it moves from the monarchy’s private chambers to a broader, eager public. Curator: Exactly. Royal portraits are never just about the individual. They’re powerful tools in shaping public perception and solidifying socio-political structures. Considering this, it changes your initial perception of Juliana’s expression, doesn't it? Editor: It definitely does. It’s no longer just a serious portrait, but a constructed image meant to reassure and impress. Thanks for opening my eyes to that! Curator: My pleasure! Seeing art in its socio-historical context always enriches the experience, wouldn’t you agree?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.