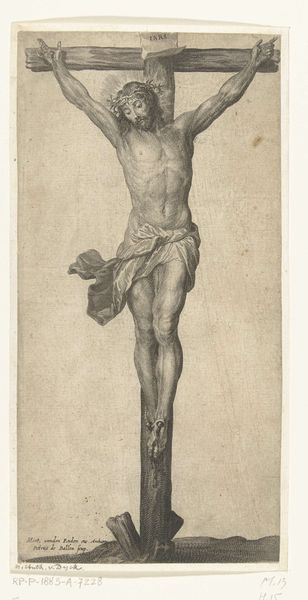

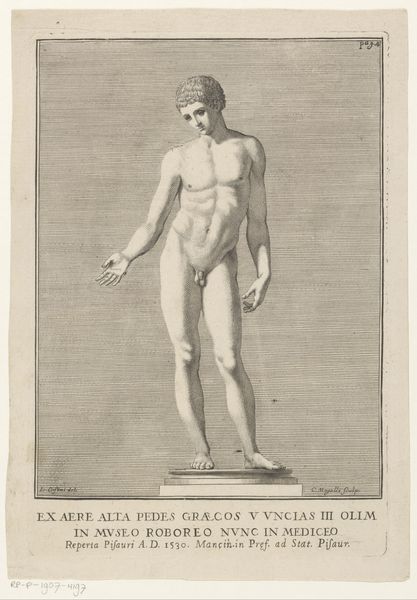

drawing, print, ink, pen, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

ink

#

pen

#

history-painting

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 710 mm, width 272 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: It’s a stark image, isn't it? The Crucifixion of Christ by Gaspar Huybrechts, likely created sometime between 1629 and 1684, rendered in pen, ink, and engraving. Editor: Absolutely, the first word that springs to mind is "anguish." The upward reaching arms, the downward cast of the head. It powerfully conveys suffering, though it's almost surgically precise in its execution. Curator: Precise is a key word. Think about the symbolic weight of the cross itself. It transcends its literal meaning as an instrument of execution and evolves into an axis mundi, connecting heaven and earth through sacrifice. That INRI inscription hovering above adds another layer—a public declaration of identity and authority. Editor: And what authority is being projected? It reads almost as propaganda, given how it presents Christ’s suffering in the nude as a deliberate, and rather sensual display of vulnerability, within a clearly patriarchal structure of power and state sanctioned murder. Curator: Perhaps, but look at how the light catches his form, highlighting the humanity within the divine. Consider the symbolic associations of light with divinity, revelation, and truth. These are tropes used consistently throughout art history and religious iconography. Editor: Right, and what "truth" are we meant to find? In this context, it seems aimed to naturalize violence through hyper-stylized and theatrical grief to justify social hierarchy through faith and martyrdom. Even the nude form becomes complicit in reinforcing narratives around power, domination, and perhaps guilt. Curator: I see your point. But I also wonder if, even within the power structure, Huybrechts might be capturing a genuine sense of loss and mourning. Consider the tradition of devotional art as a personal, even intimate expression of faith, not just public performance. Editor: But aren’t individual expressions inevitably shaped by the structures that enable them? Can we really divorce the personal from the political, especially when examining such overtly charged iconography? Curator: A question for the ages, indeed. Either way, Huybrechts presents us with potent symbolism. Editor: A symbol that demands continued questioning. It pushes me to deconstruct established narratives and interrogate what's embedded within art historical legacies.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.