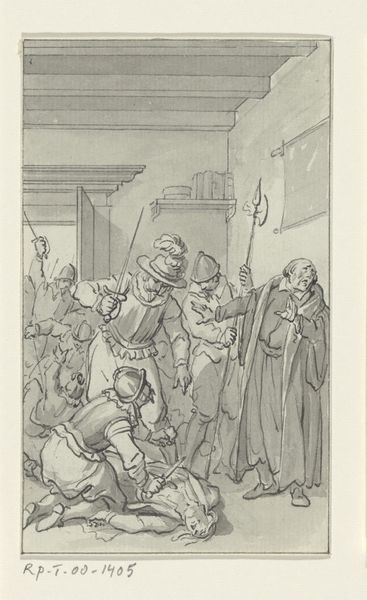

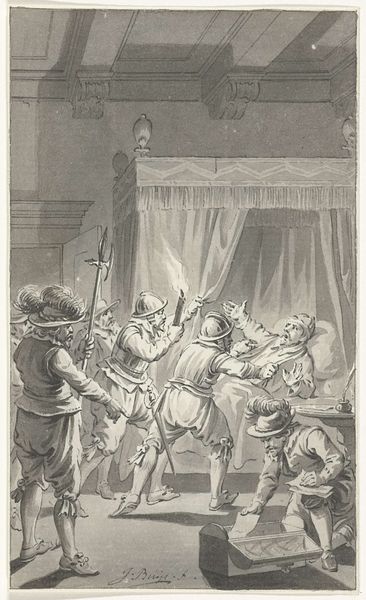

drawing, ink, pen

#

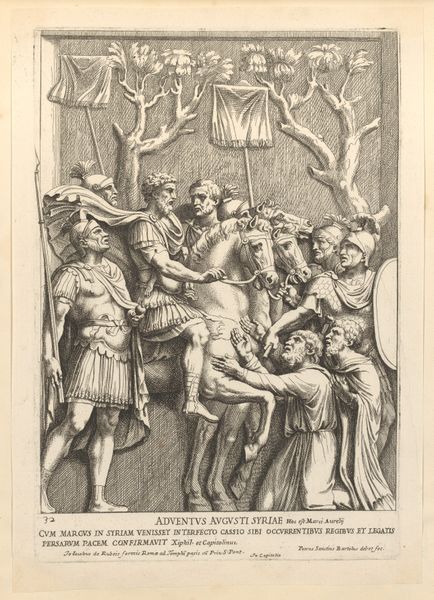

drawing

#

pen illustration

#

ink

#

pen

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 149 mm, width 90 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is Jacobus Buys' pen and ink drawing, "The Iconoclasm," made between 1784 and 1786. It feels… intense, chaotic. What jumps out at you when you look at this piece? Curator: What I find compelling is the historical moment Buys chose to depict, and even more so, the context in which he created this work. The "Beeldenstorm" – the iconoclastic fury of 1566 – was a pivotal moment in the Dutch Reformation, marking a violent rejection of Catholic imagery in churches. Editor: Right, I see that destruction represented pretty vividly here. But Buys made this drawing over two centuries later. Why revisit such a turbulent event then? Curator: Precisely. Buys was working during a period of Enlightenment ideals, where notions of religious tolerance and freedom of conscience were gaining prominence. His depiction of the iconoclasm, almost romanticizing its violence, likely served to fuel contemporary debates about religious authority and the role of the state. The drawing acts as a mirror reflecting anxieties around public order and religious expression in his own time. What do you make of the artist including a clear image of a broken bishop? Editor: That image definitely feels pointed. Highlighting that religious leader brings to the fore the struggle for power and challenges ideas of the Church's authority during this earlier moment in time. So Buys isn't just illustrating history; he's making a statement about his own era. Curator: Exactly. He’s engaging in a visual argument, prompting viewers to consider the legacy of religious conflict and the ongoing negotiation between faith, politics, and the public sphere. Editor: It's amazing how a drawing can be so much more than just an illustration. I’ll never look at historical depictions the same way again. Curator: Indeed, every brushstroke, every composition, reflects a complex interplay between the past and the present. It really forces one to analyze not just what is shown, but why and when it is being shown.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.