Dimensions: image: 439 x 579 mm

Copyright: © Thomas Struth | CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

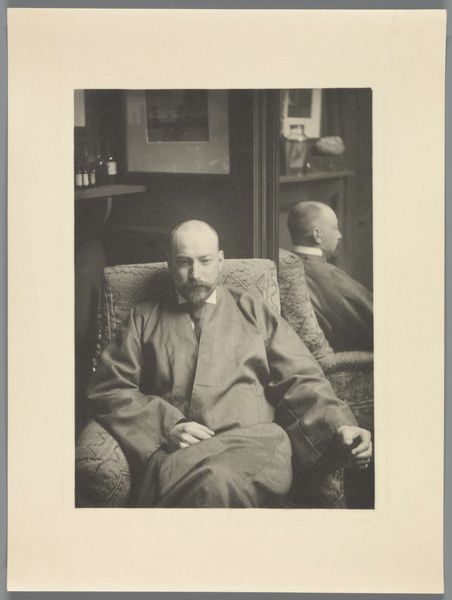

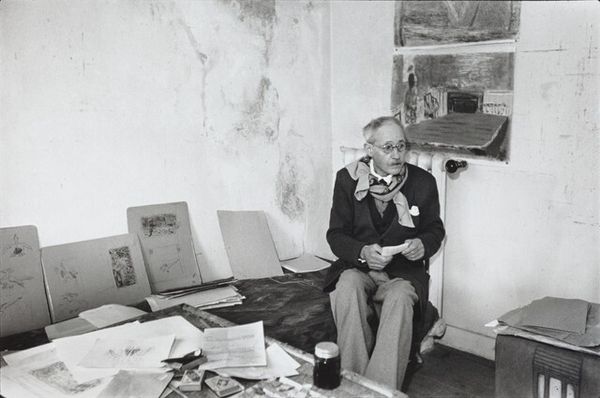

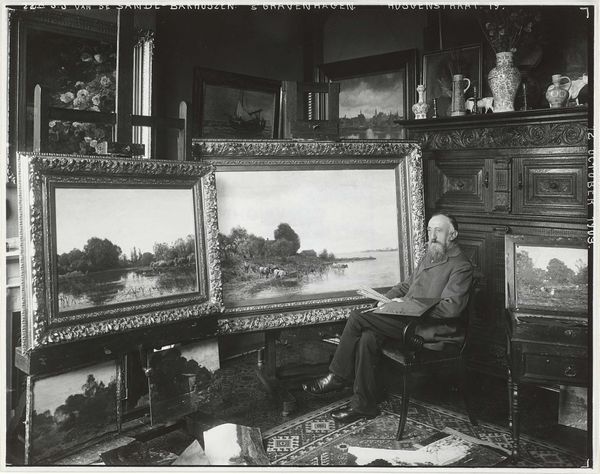

Editor: Thomas Struth's photograph, "The Late Giles Robertson (with Book), Edinburgh 1987," has such a still and quiet quality. What do you see in the composition of this piece? Curator: The photograph presents a complex arrangement of planes and textures. Note how the textured wallpaper competes with the aged surface of the table. Struth's strategic use of lighting sculpts the subject, drawing our eye through the frame. Editor: It's almost like a stage set. The sitter is framed by so much antiquated detail. Curator: Precisely. The photograph employs a rigorous structural framework. Consider the interplay of verticals and horizontals, the mirroring of rectangular forms within the paintings and the table itself. Each element contributes to a carefully constructed visual language. Editor: It’s interesting how the formal elements create such a specific mood, too. Thanks for sharing your perspective! Curator: Indeed. By analyzing the formal elements, we gain a deeper understanding of Struth's visual strategy and the photograph's overall impact.

Comments

tate 10 months ago

⋮

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/struth-the-late-giles-robertson-with-book-edinburgh-1987-p77746

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 10 months ago

⋮

The Late Giles Robertson (with book), Edinburgh 1987 is one of an ongoing series of domestic group portrait photographs that Thomas Struth began making in the mid 1980s. He had previously gained recognition for his black and white photographs of the urban environment. These works were notable for their stage-like emptiness and their concentration on architectural surfaces. However, despite the change of subject matter, the group portraits reflect his continuing desire to make carefully considered images, which present the scene before the camera in an objective manner. Compositions are simple and digital manipulation is avoided. Struth has stated: 'for me it is more interesting to try and find out something from the real than to throw something subjective in front of the audience.' (Quoted in Minelli p.190.) Struth started making portrait photographs, some of which are in colour and others in black and white, while staying with friends as he travelled the world working on the street scenes. In an interview he has stated: 'The first two portraits … I made came from purely personal incentives; on trips to Scotland and Japan … I lived with families for a couple of weeks, and at the end of the trip I wanted to take a photo of the family group as a remembrance.' (quoted in Buchloch p.29.) The resulting images were the products of a long and self-conscious process of discussion and collaboration. They are carefully considered memorials rather than instantaneous snap shots. Struth would describe the spatial limits of the image, and encourage the sitters to select the setting and their position within the frame. He would usually ask them to look directly at the camera. To obtain maximum focus and detail he employed long exposure times. This meant that in order to avoid blurring, the sitters had to chose poses they would be able to hold without moving. Struth continued to use this method for all the later group portraits, whether of friends or acquaintances In The Late Giles Robertson (with book), Edinburgh 1987 an old man, who has since died, rests an old book on the table as he poses for his photograph. He is seated behind a long dinning table in a pink-hued room which is hung with gold-framed oil paintings. He looks down towards the book on the table. His pose is thus different to that of many of the figures in Struth's portraits who look out to confront the gaze of the spectator. Yet, as in Struth's other portraits, Giles Robertson's face is both self-contained and inscrutable. This is not some private moment of meditation that Struth has surreptitiously captured. It is rather a restrained yet tender image in which Struth subtly evokes the passage of time and the life that has been lived by the learned gentleman and the objects with which he has surrounded himself. Like the old man's hands and wrinkled forehead, the scuffed, stained furniture is marked with traces of its history. Struth maintains a respectful distance. He does not offer a portrait of psychological depth but rather concentrates on appearances. In photographing Giles Robertson in this way Struth deliberately distances himself from much portrait photography which attempts to capture a fleeting, psychologically revealing moment or expression. Discussing Struth's work, the critic Richard Sennett has written: 'We relate to these images as we might appreciate strangers in a crowd; we feel their presence without the need to transgress boundaries by demanding intimacy or revelation … people guard their separateness even as they present themselves directly to us.' (Sennett p.94.) Struth's portraits encourage contemplation and investigation, inviting the viewer to reflect upon the limits of his or her knowledge of other people. Like Struth's street scenes they are intended to 'give pause' so as to bring about 'a move to investigative viewing' which is also a 'call to interact.'(Quoted in Buchloh p.31.) Further Reading: Richard Sennett, Thomas Struth: Strangers and Friends, exhibition catalogue, Institute of Contemporary Art, London 1994, reproduced (colour) p.90Giovanna Minelli, Another Objectivity, exhibition catalogue, Centre National des Arts Plastiques, Paris 1989, pp.189-194Benjamin Buchloh, Portraits: Thomas Struth, exhibition catalogue, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York 1990 Imogen Cornwall-JonesSeptember 2001