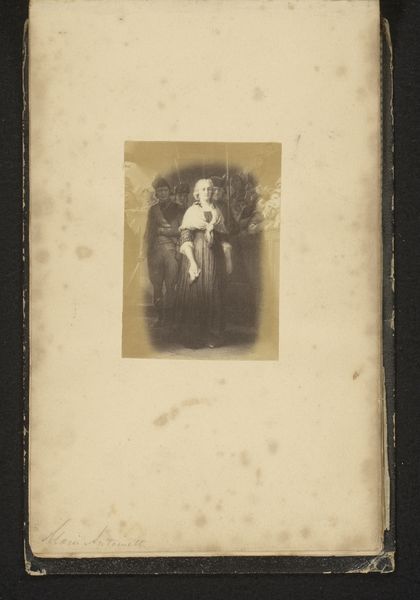

Fotoreproductie van een schilderij met Marie Antoinette die wordt afgevoerd uit de rechtszaal 1875

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 62 mm, width 123 mm, height 320 mm, width 265 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This gelatin-silver print from 1875, currently held in the Rijksmuseum, captures a striking moment. It’s titled "Fotoreproductie van een schilderij met Marie Antoinette die wordt afgevoerd uit de rechtszaal"— "Photographic reproduction of a painting with Marie Antoinette being led from the courtroom". What's your first take? Editor: Immediately, I see a study in faces, really. A solemn figure—Marie Antoinette—surrounded by a crowd exhibiting a spectrum of expressions. There's a palpable tension between her composure and their morbid curiosity. Curator: Indeed. It’s a reproduction, and one has to consider what it means to reproduce an image of this subject, in this way. Photography allowed for mass distribution and a very specific re-presentation. Gelatin-silver prints allowed for finer details and a wider tonal range which made for almost an ideal material to reproduce paintings on this scale. What social role does this image serve, then, in the wake of the French Revolution, being consumed by so many through new reproductive technologies? Editor: Symbolically, Antoinette embodies the fall from grace, doesn't she? Note how the light catches her face and that shawl. There's a softness there, a vulnerability that almost humanizes her. But then you look at the gawking faces—the symbols of revolutionary fervor—and the loaded meaning shifts, as these images of royalty were very often re-framed to send political messages. It is really about highlighting her demise and bringing attention to the end of royalty's reign. Curator: The artist’s labour here is obscured twice over—first through photographic reproduction of a painting and secondly through the way photography democratizes image distribution. As the cost of image production dropped with photographs of paintings, how does this image circulate throughout Dutch society at this time? Is it a commodity to be consumed, a cautionary tale about the excesses of the aristocracy, or simply a popular image capitalizing on morbid fascinations? Editor: Or all three, perhaps. Consider the guard's stoic gaze—almost protective. The juxtaposition subtly questions the narrative, challenging us to reflect on individual culpability versus the power of historical forces, how could the iconography have influenced perception then, and now. Curator: So it brings forward questions of consumption, commodity, labour, and representation all bound up together. These considerations allow a new understanding, not simply of this object but also its value systems and circulation methods during that era. Editor: Absolutely, understanding those visual shorthands gives us access to deeper cultural narratives—historical wounds that still resonate today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.