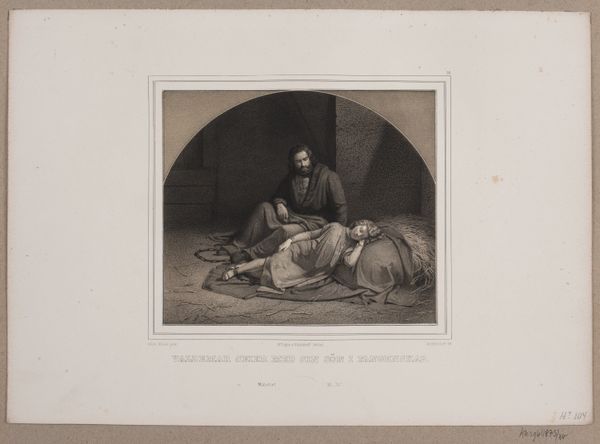

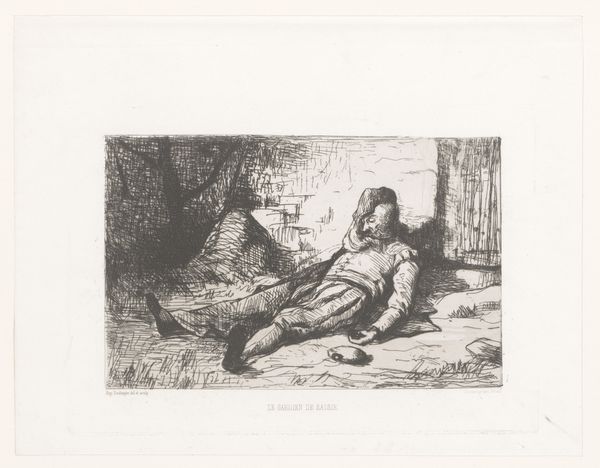

Dimensions: height 275 mm, width 356 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Today we’re looking at "Graaf Eberhard bij het lijk van zoon Ulrich," created between 1853 and 1865 by Adolf Carel Nunnink. It's housed right here at the Rijksmuseum, a poignant engraving printed on paper. Editor: It's somber. Immediately, the overwhelming grey tones communicate grief. You have the rigid formality of the armor on the dead son juxtaposed with what seems to be the raw sorrow of the father. It feels theatrical, even operatic. Curator: Exactly. This is Romanticism drawing upon historical painting— specifically, genre scenes to explore deeper questions of mourning and power dynamics within the family. Consider how societal expectations surrounding male grief are challenged in this scene, right? Editor: Absolutely. Thinking about the materiality, engravings inherently possess a reproducible quality that democratizes art. How many impressions were made? And did the reproductive nature of this engraving speak to issues of access in 19th-century art viewership, challenging the singular, unique art object? Curator: Certainly. And this act of memorializing a patriarchal lineage for public consumption reinforces dominant power structures but simultaneously acknowledges the emotional vulnerabilities of the ruling class. We can discuss what it signifies to show powerful men in moments of vulnerability or defeat, challenging conventional masculinity and how this moment shapes collective historical memory. Editor: The precision of the engraving tool itself demands a meticulous process, which contrasts beautifully with the subject's inherent messiness – death, grief, loss of dynastic continuation. There’s also the contrast of scales in the production—from individual engraver to potential mass printing and dissemination of imagery. How did the tools affect Nunnink's own emotional investment in crafting this engraving? Curator: Considering contemporary intersectional perspectives, what narratives might this engraving obscure, particularly regarding marginalized voices absent from its patriarchal framework? How can this depiction further perpetuate cycles of privilege? It certainly invites questions of visibility and power… Editor: An object inherently entangled with labor and production – which is further complicated as those systems change over time with industrialization, right? The tools, the presses—their influence is present in the final product. Curator: Agreed. Analyzing the print through an activist lens requires us to acknowledge historical power dynamics, while a materialist approach offers a tangible sense of the labor involved. Editor: It's through both the critical, engaged readings that challenge normative historical framings and understandings of process and creation that our reading of the print's layered impact is truly expanded.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.