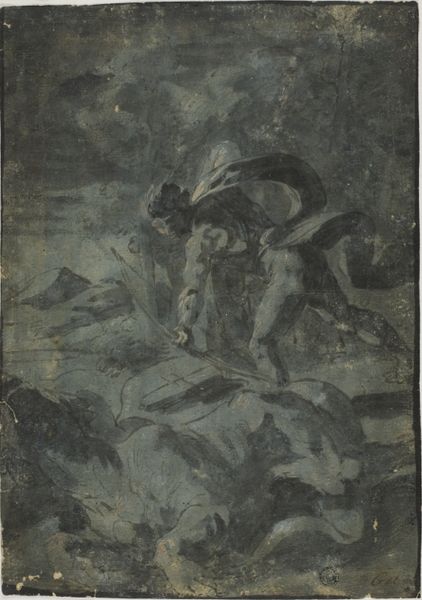

painting, oil-paint, canvas

#

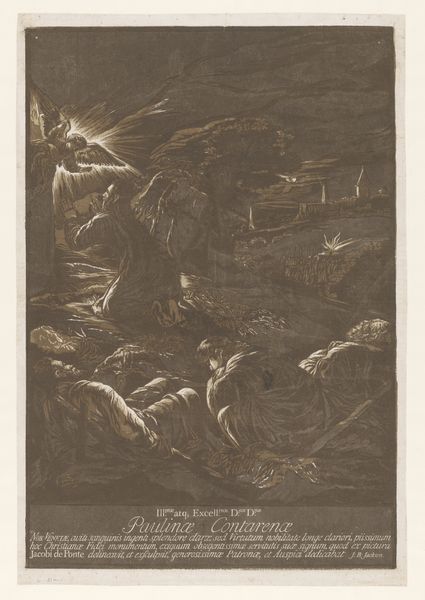

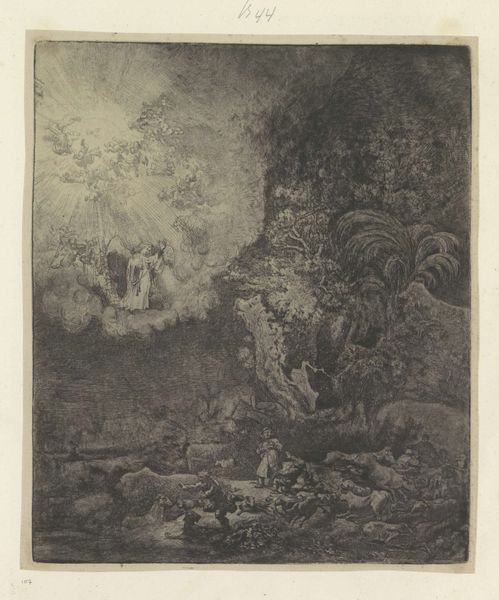

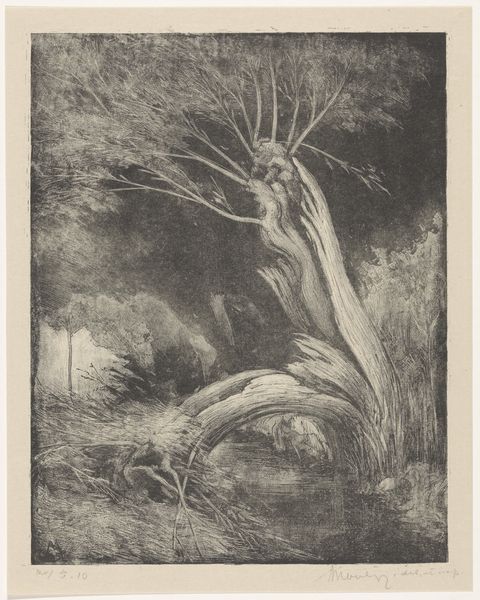

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

oil painting

#

canvas

#

vanitas

#

matter-painting

#

mixed media

#

realism

Dimensions: 60.5 cm (height) x 50.5 cm (width) (Netto), 72.5 cm (height) x 61 cm (width) x 4.5 cm (depth) (Brutto)

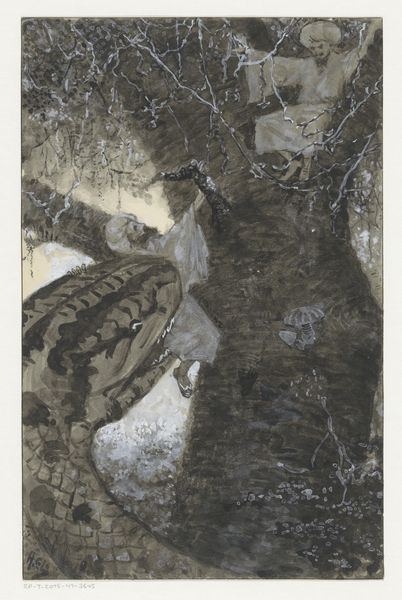

Editor: Here we have Otto Marseus van Schrieck's "Still Life with Thistle and Snake" from 1663, housed at the SMK. It's… unexpectedly creepy! The thistle looks almost alien in this dark, almost nocturnal setting. What's your take on this particular piece? Curator: Ah, yes! "Creepy" is a great word for it, and deliberate I think. Van Schrieck wasn't your typical Dutch master tossing together pleasant pastries and pewter. He was all about the *sotto voce*, the underbelly of beauty. Think of it as a botanical illustration gone rogue, wouldn’t you say? Editor: Definitely rogue! All those moths fluttering about. It's not exactly welcoming. Is the darkness typical? Curator: Precisely! The darkness intensifies the vanitas aspect. The snake, the thistle which is both beautiful and prickly, they all hint at mortality, the ephemeral nature of life. The snake is the embodiment of danger but also holds within it the concept of medicine and healing. It is more layered than one first perceives. I wonder if he kept live snakes? One has to wonder about the source of inspiration. Editor: It's hard to imagine this alongside, say, a Rembrandt. So, we have a painter obsessed with creepy crawlies contemplating the meaning of life. Curator: Essentially! And, to me, the drama isn't in grand gestures, but the miniature dramas played out under our noses. Think of it as a baroque horror film condensed onto canvas. Editor: A baroque horror film – I love that! I’ll never look at a thistle the same way again. Curator: Nor will I, and isn't that the thrill of finding these surprising perspectives across time? We engage in a new conversation.

Comments

statensmuseumforkunst about 2 years ago

⋮

Observers must exercise their imagination in order to understand the artistic and aesthetic mode of expression that the Dutch artist Otto Marseus van Schrieck painted into his peculiar paintings, for what remains today is merely a torso. Time has been unkind to van Schrieck’s paintings. Still Life with Thistle and Snake, signed and dated ”OTTO. Marseus 1663”, is no exception. Originally, the picture, especially the butterflies, would have shone brightly with its myriad colours. All that is left now is a limited palette of mossy greens, ochre yellows, and bluish greens and a meek, unassuming red used for the cyclamen and daisies in the forest floor. With this work Otto Marseus van Schrieck created a special type of painting because he “stole” wings from real-life butterflies and because of his skill at imitating the special structures found in the forest’s soft covering of mosses and lichen. Even though the butterfly dust and glorious colours are now gone, the work remains intact as a narrative. The artist’s ability to introduce a dramatic story is as evident today as when the work was made. The drama in the foreground is about the battle between good and evil; an ever-recurring topos in art. Within a second the snake will devour the butterfly. The story seems realistic, partly because details such as the snake’s windpipe have been carefully painted into its gaping maw. Nevertheless, the scene is an impossible one. Snakes have never included butterflies among their prey. With its “loans” from nature the painting is poised between natural science and art. Indeed, van Schrieck’s painting provides a scene for the merging of nature and art. Such hybrid forms were greatly treasured within the era’s encyclopaedic cabinets and cabinets of natural curiosities. One of the tropes of the Kunstkammer/cabinet concept was ”playful nature”; it was believed that nature could create images and beings on a whim (for example in the structure of a marble stone). Nature could play and art could create natural sceneries such as those found in van Schrieck’s painting. At the time, similar sensibilities were expressed by Kunstkammer exhibits that combined natural objects with an artisan’s craftsmanship in equal measure. Otto Marseus van Schrieck’s paintings were popular collector’s items, not least because they made excellent “conversation pieces”. When the collector showed his guests his cabinet of curiosities van Schrieck’s approach offered a chance to present an entertaining anecdote, and, importantly, the scenes depicted provided a moral lesson for the observers’ edification.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.