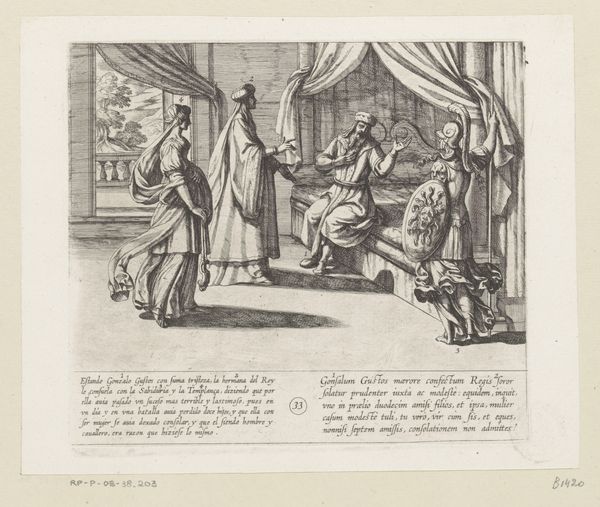

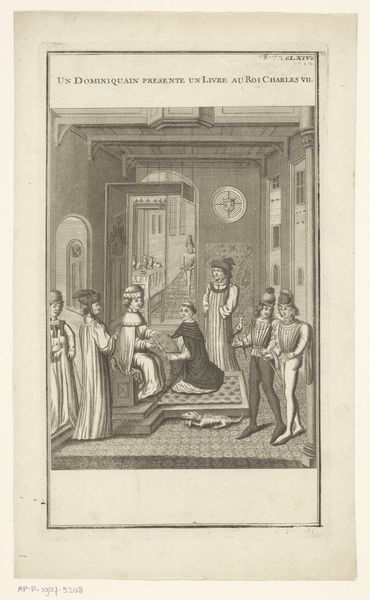

De zonen van Lara worden tot ridder geslagen door Garci Fernandez 1612

0:00

0:00

antoniotempesta

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 185 mm, width 206 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is "The Sons of Lara Being Knighted by Garci Fernandez," a 1612 engraving by Antonio Tempesta, currently housed at the Rijksmuseum. The details are impressive, but there's a starkness to the black and white that, for me, clashes with the grand ceremony it depicts. How do you read this piece? Editor: I notice how the act of producing engravings involved skilled laborers, workshops, and economic systems to distribute these images. This brings attention to who consumed these images, and for what purposes. What's the relevance of situating this image in a broader context of production and distribution? Curator: Absolutely. Consider the materials: the copperplate, the inks, the paper. Each had its own economic value and determined the artwork's accessibility. An engraving like this served as a visual commodity, circulating ideas and narratives among specific audiences. Who was Tempesta's intended audience, and how would that influence his choice of subject matter and style? Editor: It also changes how we think about authorship, doesn't it? While Tempesta designed the image, various artisans participated in making it, affecting its final form. Does that diminish his role, or does it complicate our understanding of artistic creation? Curator: It's definitely more complex. It challenges the Romantic notion of the solitary genius. This was collaborative labour, influenced by patron demands and market trends. We are discussing history here, can we overlook these elements? Editor: I suppose that to ignore them would be to look at art through too narrow a lens, focusing only on aesthetics rather than understanding the social and economic forces behind the image. Thank you, I have learnt more than expected! Curator: It’s important to acknowledge the collaborative nature of art production and appreciate the skilled labor that often goes unseen.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.