Ceremoniële kledij van een ridder van de Orde van de Kousenband 1617 - 1677

0:00

0:00

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 118 mm, width 74 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

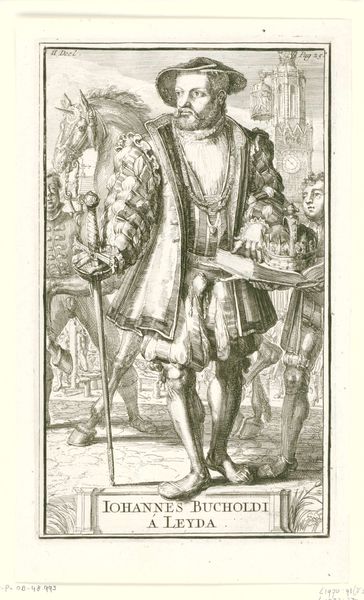

Curator: Here we have Wenceslaus Hollar’s “Ceremonial Dress of a Knight of the Garter,” made sometime between 1617 and 1677. Editor: My immediate impression is that the etching evokes a stiff formality, but somehow playful? The sheer ornamentation seems to delight in excess, especially when paired with such carefully-rendered textures. Curator: That tension is exactly what Hollar captures so well. The Order of the Garter itself—the symbols, the rituals—they all reinforce social order through carefully constructed images. The clothing *is* the man, in a way. He's the symbolic embodiment of power. Editor: Right. It makes you wonder, who created the garment? And how many hands did this finery pass through before ending up on the knight? I imagine this print being circulated among artisans—a material record almost, showcasing craft. Look at how Hollar depicts the lace ruff. It's like advertising luxury production! Curator: Indeed! Lace often symbolizes refinement, wealth, status... even a kind of spiritual purity. Each tiny loop, repeated, is like a prayer bead or mantra, elevating the wearer closer to God...and definitely further from the common peasant! The whole Order is about perceived divinity. Editor: Don't forget the material costs and time for engraving itself. Was it common to circulate prints like these for other craftsmen or aspiring gentry who craved admittance into court circles? Curator: Probably both. It speaks to a much wider social craving for upward mobility, visually encoded in clothes and represented, perhaps, by that single staff. Editor: Seeing the material cost to craft is not all that dissimilar from our obsession today with revealing "the labor" of creation; except the people actually benefitting here remain only those closest to court. That staff he holds suggests that no physical exertion occurs now—someone else, of lower social ranking—does everything. Curator: Well, there is something about the careful rendering of the robes, versus the quick scribbles used to define background and floor. Maybe it represents how even something seemingly secular, like fashion, reflects timeless aspirations of power, status, and connection to something transcendent. Editor: Or just making visible a stratified division of labor and consumption! I keep coming back to how carefully delineated those surfaces are… an aesthetic achievement representing concrete, worldly, making and commerce. Curator: Regardless, it offers an important window into both the spiritual aspirations and the material conditions of 17th-century society. Editor: Exactly, we can learn to appreciate an object for multiple reasons.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.