Dimensions: 4 3/8 x 6 3/8 in. (11.11 x 16.19 cm) (image, sheet)

Copyright: No Copyright - United States

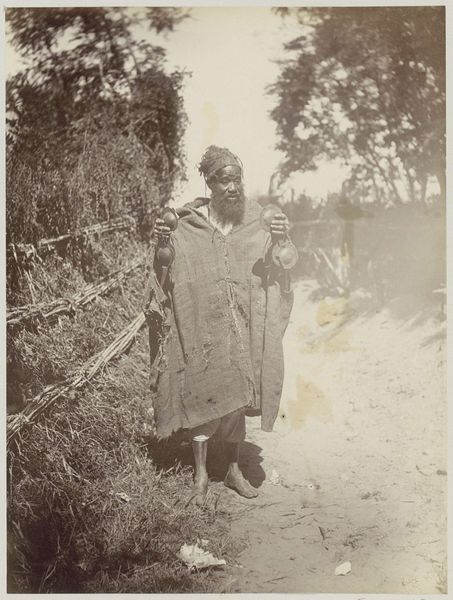

Curator: Standing before us is Lewis Hine’s "Untitled" gelatin-silver print, created around 1913. It’s currently part of the Minneapolis Institute of Art's collection. Editor: My first thought? Melancholy. The barefoot boy seems so alone, vulnerable in this stark, light-filled street. Curator: Hine's mastery is evident in how he harnesses the gelatin-silver process. Notice the tonal range, how the highlights practically glow against the shadows, and its direct relationship to social realism. It mirrors the urban textures, doesn’t it? It highlights a gritty environment. Editor: Absolutely. Given Hine's work exposing child labor, the social commentary seems unavoidable here. This image, to me, speaks volumes about the realities faced by marginalized children a century ago – perhaps the shirt being too large indicates donated clothes, pointing toward poverty and lack of resources. It’s a silent protest against injustice. Curator: Indeed, the material context deeply informs our interpretation. The accessibility of photography allowed Hine to disseminate these images widely. He utilized photojournalism as a means of activism. The gelatin-silver process itself became a tool for social reform, highlighting societal labor practices. Editor: Consider too, the gaze of the boy. There is defiance there. It's a refusal to be simply a victim. It prompts the viewers to think critically about how societal structures marginalize youth, particularly within racialized or lower-class communities, then and now. Curator: Right, and even how we consume these images is critical. Photography democratized the act of documenting social issues, challenging the established hierarchies of art production. How do we reconcile the exploitation depicted within the production of art, versus the ethics behind why an image is created in the first place? Editor: This tension you describe, I think, invites deeper discussions. How art is implicated within broader cultural narratives shapes our historical perception. It forces viewers like ourselves to actively engage with complex topics on gender, labor, class, and justice. Curator: Looking again, the tangible grit of the photographic paper lends an undeniable immediacy to his representation. Considering its place in social reform history brings its process and materials further into focus. Editor: A work that reminds us that beyond aesthetics, art has the power to serve as both historical witness and call for change.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.