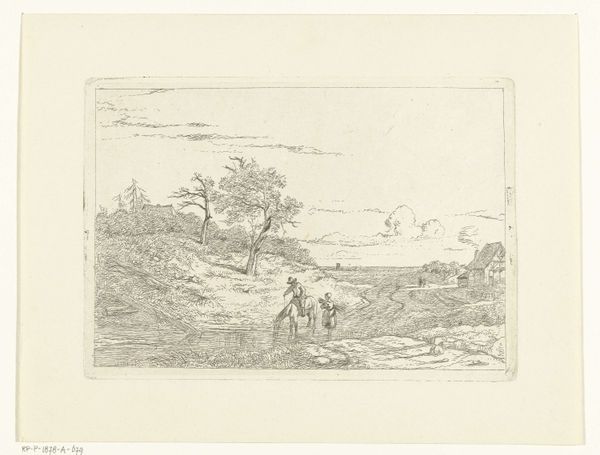

Landschap met vrouw en kunstenaar die de lager gelegen stad tekent 1831 - 1877

0:00

0:00

adolphealexandredillens

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 134 mm, width 188 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Adolphe Alexandre Dillens’ “Landschap met vrouw en kunstenaar die de lager gelegen stad tekent,” which translates to “Landscape with woman and artist drawing the lower town,” created sometime between 1831 and 1877. It is composed of etching and engraving on paper. Editor: It’s moody, isn't it? Dark sky, even darker foliage in the foreground. The architecture in the town looks gothic, adding to the atmosphere. Curator: Indeed. Dillens places the artist and his female companion, significantly, above the town, reinforcing the Romantic ideal of the artist as observer and interpreter of the world. We can look at this through a gendered lens: who is given the agency to create, to depict? And what societal structures enabled him, while perhaps restricting her to a more passive role? Editor: The labour involved is fascinating. You can really see the hand of the artist in the dense, meticulous etching. The choice of printmaking itself, engraving in particular, highlights reproducibility, which makes me consider who would have had access to an image like this and what those implications are. How might distribution of the image change its impact on viewers? Curator: Excellent points. The print’s circulation speaks volumes about societal structures. It reflects the dissemination of Romantic ideals to a bourgeois audience, shaping their understanding of nature, art, and perhaps even their own social standing in contrast to both the artist and the urban workers toiling in the city below. Editor: Thinking about that city below, consider how the act of artistic production is presented. The tools are simple—drawing implements—yet the perspective elevates him, literally and figuratively. The image’s production relied on specific tools and labor—the metal plate, the press—aren’t these absent presences worth noting? Curator: Absolutely, and this engraving captures a key tension within the period, idealizing creative independence while being firmly rooted in the material conditions of 19th century life. It reminds us that romantic notions of the solitary artist are just that: romantic notions, not fully reflective of the reality of artistic production. Editor: I appreciate how analyzing its construction reveals how social stratification has historically informed what art is considered high versus low. I leave appreciating how Dillens documented these social contexts through this reproducible medium. Curator: For me, understanding how these kinds of prints contributed to the construction of artistic identity, especially as entwined with gender and class, allows for richer and more relevant contemporary engagements.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.