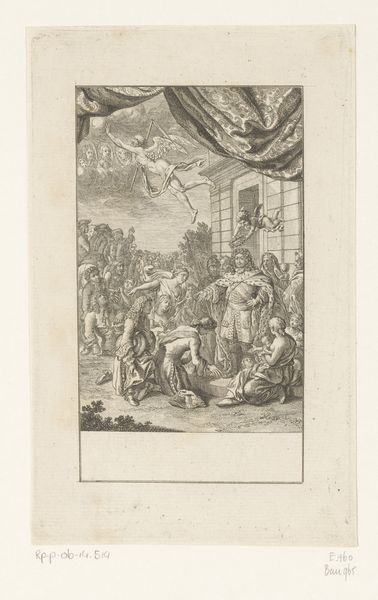

Figuren rond een allegorisch grafmonument voor John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough 1735 - 1741

0:00

0:00

engraving

#

light pencil work

#

baroque

#

mechanical pen drawing

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

form

#

personal sketchbook

#

pen-ink sketch

#

line

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pencil work

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 646 mm, width 416 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this piece by Laurent Cars, made sometime between 1735 and 1741, I’m immediately struck by its stillness, despite the obvious grandiosity of the subject matter. Editor: It's an engraving, so stillness is almost inherent in the medium, isn't it? Though you’re right; it depicts such a staged, manufactured display of power, with the Duke immortalized in stone, and all those meticulously rendered figures milling around. You can practically feel the political machinery at work here. Curator: Exactly! It's entitled "Figures around an allegorical monument for John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough.” What interests me most is how Cars uses the engraving process itself – those delicate lines etched into the copper plate, the conscious distribution of ink – to construct and communicate power. It’s not just about the image of Marlborough; it’s about the material creation of his enduring image. Editor: And that image, perpetuated and circulated via printed reproductions, speaks volumes about the social function of art in the 18th century. Think of who had access to these engravings, and where they might have been displayed: demonstrating and solidifying Marlborough’s place in the national consciousness, long after his death. These aren’t mere portraits; they're carefully crafted tools of political memory. Curator: Right. And look closer – the level of labor that went into making each impression. This engraving represents a significant investment, not only financially but also in terms of skilled craftsmanship. It's a luxury commodity as much as a memorial to a Duke. Editor: Absolutely, it reminds us how art wasn’t a purely aesthetic endeavor. Its purpose was intimately entwined with patronage, class, and the control of narrative. Seeing that level of control exhibited is jarring now, I think. Curator: Indeed. It highlights how perceptions of power and commemoration were manufactured through material processes accessible to a limited few. Editor: Considering the socio-political impact of such engravings reframes how we think about their function, shifting away from just appreciating skillful aesthetics. Curator: It's important that the process of dissemination and labor comes forward alongside its beauty, because we start asking what value and narratives it upheld, in its time, and today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.