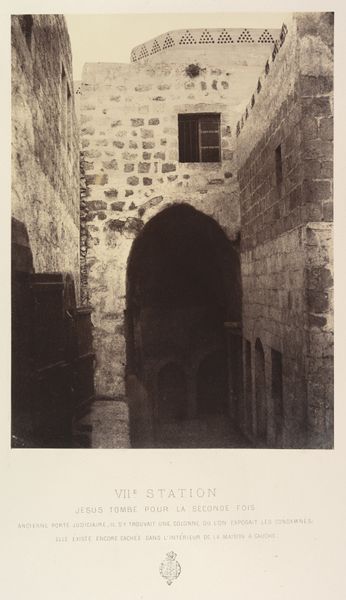

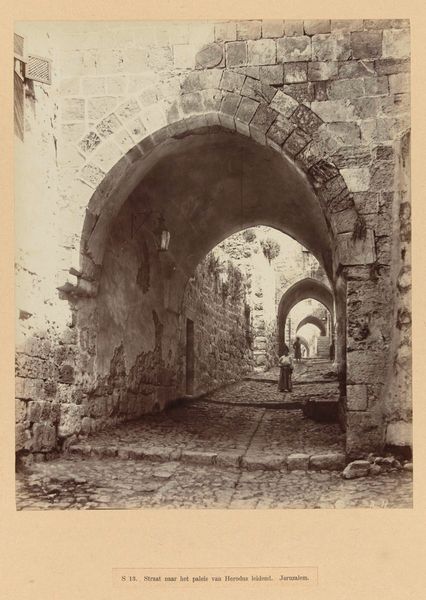

IIIe Station. Jésus tombe pour la première fois. Une colonne brisée et entendue a terre indique la place de cette station au lieu où la voie douloureuse tourne brusquement a gauche 1860

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: Image: 11 in. × 8 1/4 in. (28 × 21 cm) Mount: 17 15/16 × 23 1/4 in. (45.5 × 59 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

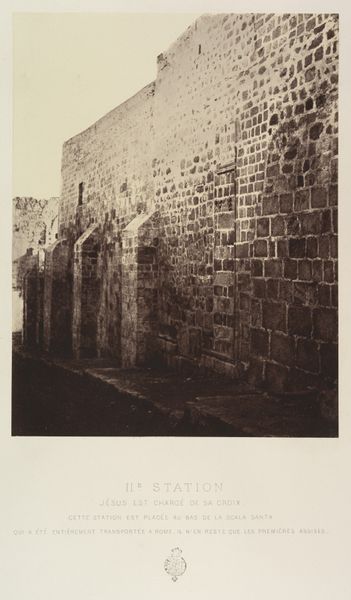

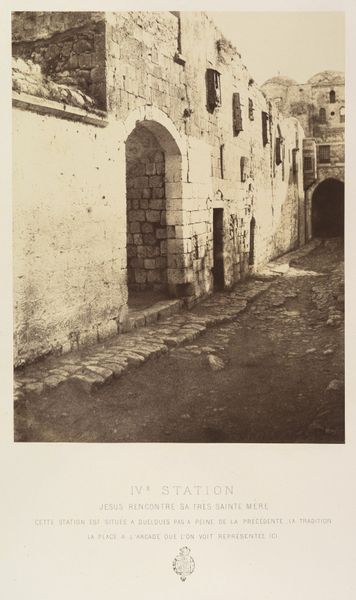

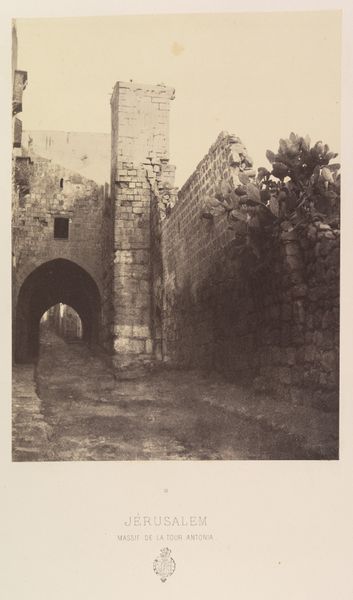

Editor: This albumen print, taken in 1860 by Louis de Clercq, depicts the IIIe Station of the Via Dolorosa: "Jésus tombe pour la première fois." There’s a palpable sense of starkness to the image, almost a ruin-like quality to the architecture. What strikes you about the work? Curator: Well, what immediately grabs my attention is how this image functions as a historical document, especially considering its relationship to the romanticism movement. Think about it: photography in the mid-19th century wasn't just about capturing reality, it was about constructing it, presenting a specific vision of the world, or, in this case, the Holy Land. Editor: So, it’s more than just a simple depiction of the location. Curator: Precisely! The broken column, for instance, positioned to mark the station. De Clercq isn’t just documenting; he’s staging a scene, emphasizing a particular interpretation of religious history, making it very evocative and very charged. The way the photograph creates a sense of place and time makes you feel like you’re present there with Jesus as he stumbles in the photograph. Editor: How much of the image do you think is reality and how much of it is staged based on De Clercq’s imagination and desire? Curator: The realness lies in the materiality, but remember, photographs were consumed within a very specific social and cultural context of orientalism, biblical tourism and European power, influencing our perception to a large degree. By creating this very somber almost eerie architectural landscape in his art, he constructs and feeds into the already-built stereotypes and attitudes of his contemporary society. Editor: That’s fascinating. So, viewing it now, we are not just seeing a depiction of a holy site, but also glimpsing into the mindset of 19th-century European views of religion, and "the other," influencing a narrative of faith and history. Curator: Exactly. Looking at art and specifically photographs as evidence is an important element. The very act of image-making carries political and cultural weight. Editor: I've certainly got a deeper appreciation for how historical context shapes a photograph, and how cultural forces frame something seemingly as ‘objective’ as an image. Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.