Dimensions: support: 330 x 381 mm

Copyright: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

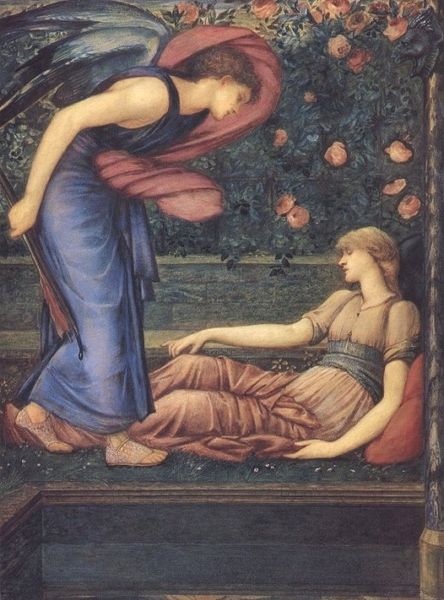

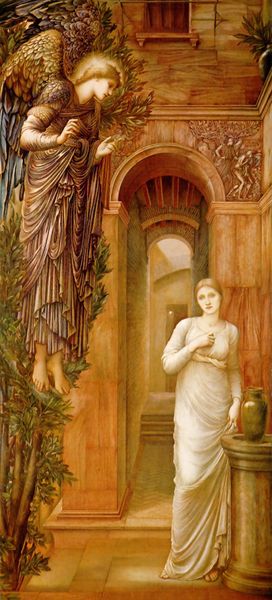

Curator: Simeon Solomon's "Sappho and Erinna in a Garden at Mytilene," housed at the Tate, presents a tender scene. It seems dreamlike, almost muted in its tones. Editor: The use of watercolor and gouache on paperboard is really interesting here, allowing Solomon to achieve that soft, ethereal quality. What’s compelling is how this technique was embraced in a period when Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics valued precision, highlighting the artist's unique approach to materials. Curator: Absolutely. Solomon's work existed within a socio-political landscape deeply concerned with morality and gender roles, so it makes sense that the image itself, the act of depicting Sappho and Erinna in an intimate setting, takes on a historical significance, challenging conventions. Editor: And considering the historical context—Solomon's later personal struggles and social marginalization—the artwork gains even more complexity. The subtle blurring of lines and the emphasis on the intimate connection between the figures speak to a fragility, echoed in his material practice. Curator: It’s interesting to consider how museums display works like this today, reframing historical narratives around sexuality and identity. Editor: Indeed, a testament to how material choices and cultural context can shape our interpretation of art.

Comments

tate 8 months ago

⋮

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/solomon-sappho-and-erinna-in-a-garden-at-mytilene-t03063

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 8 months ago

⋮

The picture depicts Sappho embracing her fellow poet Erinna in a garden at Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. Sappho was born at Lesbos in about 612BC. After a period of exile in Sicily she returned to the island and was at the centre of a community of young women devoted to Aphrodite and the Muses. Although Solomon believed Erinna to have been part of this community, we now know that she lived not on Lesbos, but on the Dorian island of Télos, and slightly later than Sappho, at the end of the 4th Century BC. Sappho wrote nine books of poetry, of which only fragments survive. The principal subject of her work is the joy and frustration of love and the most complete surviving poem is an invocation to the goddess Aphrodite to help her in her relationship with a woman. The Tate collection includes a study for the head of Sappho (1862, Tate T03104) which was drawn two years before the watercolour. She is crowned with laurel and has dark, Mediterranean, slightly androgynous features. She represents a 'masculine' foil to Erinna's seductive femininity, emphasised by the soft flesh tones, partially exposed breasts and shoulder. Their love for each other is emphasised by the pair of doves seated above them. Sappho is identifiable through her traditional attributes: the lines of poetry and the musical instrument set to one side. Plato called Sappho the tenth muse, which possibly explains the presence of the deer, sacred to Apollo. Solomon was a close associate of the Pre-Raphaelites and his work owes much to Rossetti (1828-82) and Burne-Jones (1833-98). The influence of Rossetti, and more especially the poet Swinburne (1837-1909) - who was influenced in turn by Sappho's poetry - led him to explore the forbidden subjects of homosexuality and lesbianism. However, he was unable to conceal his own sexual preferences and on 11 February 1873 was arrested for homosexual offences. Thereafter he was shunned by the very artists who had encouraged his daring subject matter. This work was bought by James Leathart, who owned a number of works by Solomon, all dating from the early 1860s. He probably bought the picture directly from the artist, or through the agency of Rossetti. Further reading:Elizabeth Prettejohn, The Art of the Pre-Raphaelites, London 2000, p.222-3, reproduced p.222, in colour.The Tate Gallery Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions 1980-82, London 1984, p.35, reproduced p.35.Christopher Wood, Victorian Painting, London 1999, pp.223-4, reproduced p.224, in colour. Frances Fowle December 2000