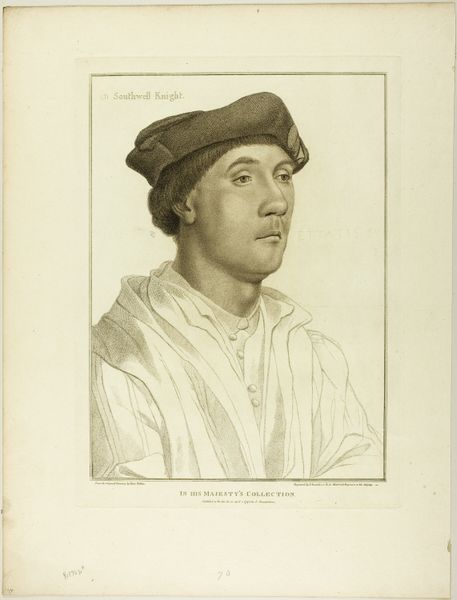

Fotoreproductie van een portret van Richard Southwell door Hans Holbein before 1877

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

drawing, paper, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

pencil drawing

#

sketch

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

northern-renaissance

Dimensions: height 346 mm, width 263 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

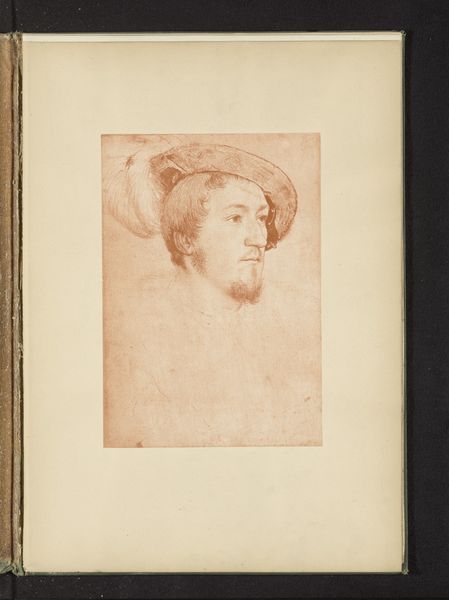

Curator: This is a photographic reproduction of Hans Holbein's portrait drawing of Richard Southwell, made sometime before 1877, currently held in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My immediate reaction is one of austerity. The sharp, spare lines of the rendering give a strong impression of someone quite reserved, perhaps even formidable. Curator: Absolutely. Holbein was a master of portraying the psychology and social standing of his subjects. Richard Southwell, a prominent figure in Tudor England, served under Henry VIII, including during the dissolution of the monasteries. His presence in the King's circle would have meant he possessed real power, but he also had to operate within very constrained limits. Editor: Yes, that comes across strongly. Southwell’s gaze seems carefully neutral, withholding judgment. The hat, the almost severe lines of the garment, seem intended to project an air of solid reliability—necessary qualities for those who survived in that era! I see the face, the eyes, and find my mind traveling toward other portraits where the eyes communicate more feeling. These eyes tell little beyond alertness. Curator: This neutrality becomes a powerful tool for conveying a certain…ambivalence. Southwell was a complex figure. He participated in some rather dark events, aligning himself with Cromwell during the suppression of religious orders, events we view as traumatic for many sectors of society. There is an understanding of trauma within this image. Editor: That’s fascinating to consider. And looking again, I see hints of calculation behind the composed expression. The slight pursing of the lips, almost imperceptible, seems to suggest a mind constantly assessing risks. The age too becomes quite potent as an idea, especially since that time in Europe was replete with people aged before their time, and carrying within them the horrors they had witnessed. Curator: Precisely. The very medium used is symbolic. A pencil drawing, especially one that was photographically reproduced, can underscore issues of accessibility and historical documentation. We can view Southwell and ask questions about access and accountability even in contemporary society. Whose stories are preserved, and whose are marginalized? Editor: The drawing on paper almost enhances a sense of that era. It is an intriguing thought process, because you realize that many portraits and many images have come down to us and have been passed on to other eras through documentation. A thread through time. Curator: Agreed, there is something quite enduring. And looking at it now, I am drawn to reflect upon the very ideas and politics behind how a portrait can shape and sustain collective memory. Editor: The very existence of images becomes about collective memory, yes, but the symbols too, become embedded deep within our psyche, in a continuous loop of psychological patterns.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.