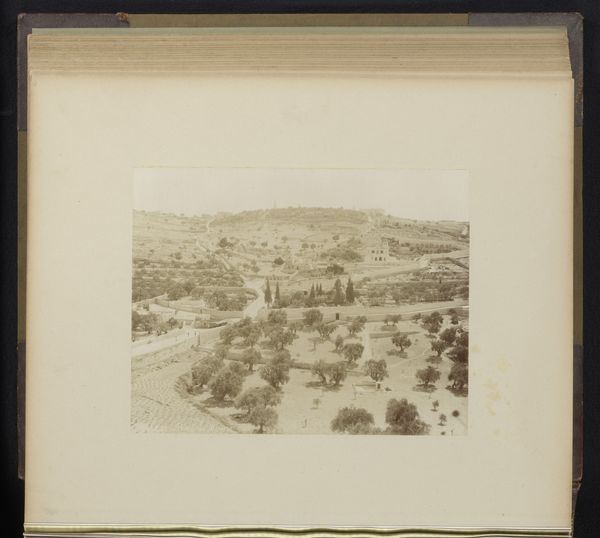

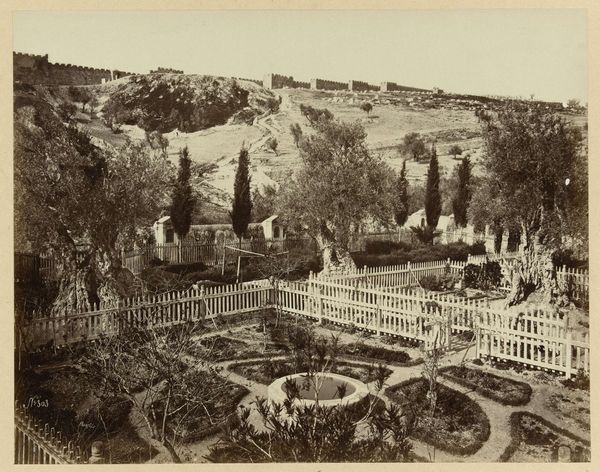

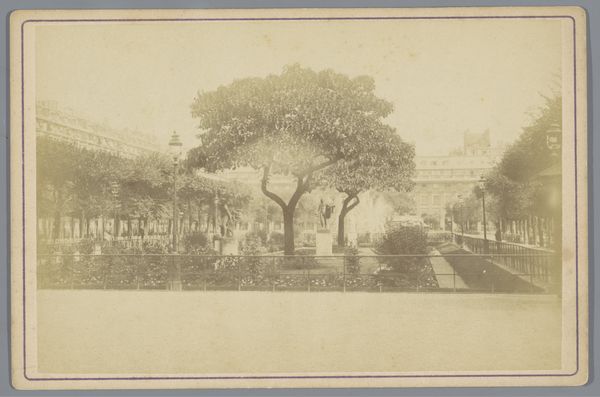

Tuin van Getsemane, Olijfberg bij Jeruzalem, Palestina c. 1850 - 1900

0:00

0:00

maisonbonfils

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 218 mm, width 276 mm, height 337 mm, width 395 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this sepia-toned photograph, “Tuin van Getsemane, Olijfberg bij Jeruzalem, Palestina”, attributed to Maison Bonfils and dated around 1850 to 1900, I find myself transported. What strikes you initially? Editor: That unrelenting light! It washes everything in an almost bleached uniformity. It flattens the scene, really putting forward the hard work needed to keep that landscape orderly. Curator: There's a certain deliberate composition to it, wouldn’t you agree? The way the garden's meticulous layout is contrasted against the seemingly wilder terrain behind the wall… almost feels like an assertion of control. I can almost smell the earth just by gazing upon this little place. Editor: Control definitely plays into it, and thinking about this as a gelatine silver print puts things in context: we’re talking about laborious chemical processes, careful manipulation. The materiality is intrinsic to how the image reads; colonial photographers traveling and documenting faraway landscapes, carefully creating marketable images. This particular print is an aesthetic artifact as much as it is any kind of supposed document. Curator: Right, because that is what Maison Bonfils was known for: catering to a Western audience's fascination with the ‘Orient’ during that period, perpetuating a very particular kind of gaze. There's a real blend here of something that resembles ‘documentary’ mixed with very painterly intentions that lean heavily on romantic and exotic sentiments. Editor: Yes, that fence. To the modern eye, something is terribly sad and ironic about how that sharp barrier delineates nature at what is meant to be one of the holiest, spiritually bountiful spots on Earth. Look, a garden wall and beyond it more garden walls: How much of this biblical and picturesque location did visitors actually get to visit or experience? How much did people work and were restricted to tend and maintain that highly restricted earth? Curator: I imagine encountering this garden – or this image of it – must have resonated profoundly with a lot of Westerners making the pilgrimage to Palestine in that time. It confirms and comforts their idea of the “Holy Land” and is safely packaged in a nice little photograph to take back home. A world away from their everyday existence and just on the edge of real experience. The romanticizing of even such heavy stuff as faith, labor and loss strikes me profoundly when viewing this picture. Editor: Exactly, and unpacking the layers of mediation is crucial. These weren't objective records. Curator: Not at all, so thinking about those layers... I suppose the photograph really highlights how what we're seeing isn't some authentic window, but an authored perspective filtered through artistry and politics. Editor: Indeed. Thinking about photography of that era being sent across countries as exotic postcards gets me going! I could reflect on such an image for much longer, and the garden there that serves as metaphor for a way to consider value and authenticity!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.