painting, oil-paint

#

16_19th-century

#

painting

#

impressionism

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

oil painting

#

cityscape

#

realism

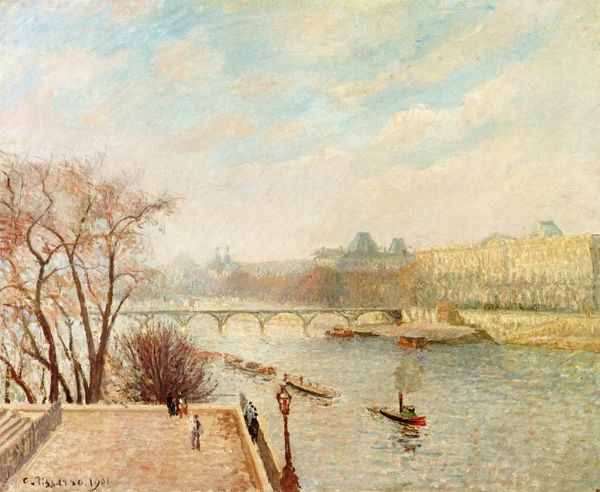

Dimensions: overall: 40.2 x 55.1 cm (15 13/16 x 21 11/16 in.) framed: 57.8 x 73 x 6.9 cm (22 3/4 x 28 3/4 x 2 11/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

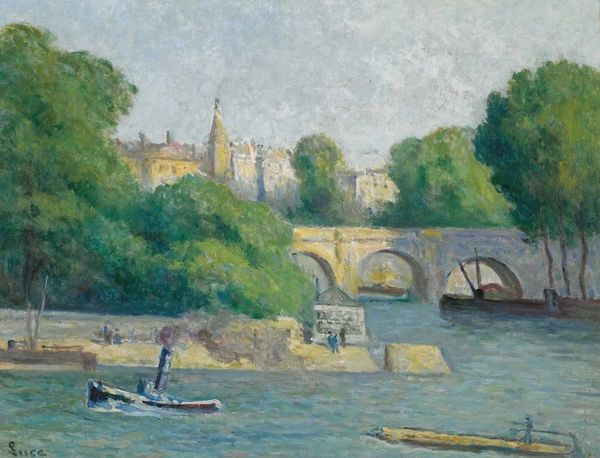

Curator: Today we're looking at "Pont de la Tournelle, Paris," painted in 1862 by Stanislas Lépine. Editor: The initial impression is one of serenity. A hazy, almost muted palette with strong horizontal lines that suggest tranquility and stillness. It feels classically composed, in a way. Curator: Indeed. Note how Lépine utilizes a relatively limited range of colors, primarily earth tones, blues, and creams, which contributes to the overall sense of calm and the subtle gradations of light on the buildings and the water's surface. The composition adheres to a classic structure: the bridge and buildings form a solid, grounded mass, while the sky and water provide a more atmospheric, expansive contrast. Editor: But let's also consider the people along the riverbank. Their presence tells a story of everyday life, of access and leisure in this cityscape. The bridge, while structurally dominant, doesn’t overshadow the lived experiences occurring right there on the shoreline. Who had the privilege of leisurely loitering on the banks of the Seine in 1862, and who did not? What class dynamics are at play in this seemingly simple waterside scene? Curator: An interesting interpretation, to think about it within the context of class, as those buildings and their reflection function as formal elements creating symmetrical effect. There's an almost mathematical harmony between the built environment and nature. Notice the subtle play of light and shadow which gives volume to the buildings while the reflections create inverted mirroring across the river, and unify the two sides formally. Editor: While aesthetically appealing, it’s important to think about the historical conditions of Paris during this period—the widening gap between the rich and poor during the Second Empire, Haussmann's urban planning that displaced working-class neighborhoods… These issues are not explicitly present, of course, but the exclusion they created is notably felt in what IS portrayed: a leisure scene free from industry that overlooks social unrest. Curator: So while you read that exclusion, the artist creates harmony in an almost idyllic scene which allows the eye to wander and rest, an example of art historical development through subtle progression and classical references. Editor: I see your point; it’s in the painterly stillness, then, that we're reminded that progress comes at the expense of the less privileged in the backdrop of urban landscapes. Curator: Perhaps what we're seeing here is that tension and complexity in a singular, still moment. Editor: I'll have to keep these dual narratives in mind the next time I come across this painter.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.